The accusation of “causing division” has been leveled routinely in national discourse over the last nine months, often in the context of Australia’s complicity in the genocide in Gaza. Pro-Palestine protestors, politicians, activists and academics are routinely accused of instigating division in our respective communities for calling for the government to cease supporting Israel.

Shortages of health-care, food, water and safe places of shelter amidst cuts to humanitarian aid are daily realities for Palestinians. And whilst our Labor government are seemingly content with this ongoing crisis, they continue to support those who propagate the very division they accuse others of. Preserving the image of the nation as “inclusive” is paramount. Speaking about the murder of Palestinians tarnishes that image, and actions to stifle dissent — as in the case of Senator Fatima Payman — are taken swiftly.

The terms “Inclusion” and “diversity” — as feminist scholar Sara Ahmed suggests in On Being Included (2012) — are used to soften the image of institutions whilst obscuring the ways in which racism and prejudice continue to operate. We are supposed to imagine that the settler-colonial nation has embraced a new and improved “inclusive” form. We are supposed to imagine that the nation has the capacity to embrace all people.

*

Increasingly, I refer to myself as disabled rather than autistic and disabled. Not because I am ashamed of being autistic, but rather, because I am troubled by what autism has come to represent. The divisions between conceptions of autism as “difference” and as part of the broader disabled community particularly concern me. Autism is increasingly being located as separate from disability, a trendy quirk, and I worry that disability is yet again rendered “other” in order to serve autism’s “inclusion”.

I began my PhD, which examines discourses on autism, disability, work and gender, at the end of 2021. As part of my project, I examined the Senate Select Committee on Autism hearing transcripts, the hearings that led to the creation of a National Autism Strategy.

The strong consensus between autistic people who attended the hearings, advocates, medical professionals, researchers and policymakers stood out immediately, leading to the construction of an image of an “inclusive” nation where autistic people are an “untapped resource” and a “national treasure”, particularly when it comes to work.

This consensus made me uneasy, as I wondered what this particular platforming of autism meant for the broader disabled community. I wondered about who might benefit from what was often framed as autistic “inclusion”, and how this might come to be.

In Feminism Without Borders (2003), Chandra Mohanty writes about capitalist models of citizenship, and this seems to be in part why the lure of work and the promise of financial security for autistic people is held out as so transformative by those in favor of a National Autism Strategy. Unfortunately, what it also means is that autistic people become a product for the nation to use as evidence of its “inclusivity”, an outcome that is presented as desirable for autistic people.

One primary way autism “inclusivity” legitimates this strategy is in portions of the transcripts that support a program modeled on the Israeli Defence Force Ro’im Rachok unit. This unit employs autistic people in the Israeli Defence Force in cybersecurity and intelligence roles, and was noted as an exemplar model for autistic employment — one that could and should be replicated.

This troubling use of autistic employment as evidence of nation-state exceptionalism recalls Jasbir Puar’s description of how Israel uses LGBTQ+ acceptance as a tool to obscure its colonial violence towards Palestinians (what Puar names as homonationalism and what has come to be known more popularly as “pinkwashing”). The draft strategy, which only identifies work as a key area, means that the use of autism as a nation(alist) tool is not something the disabled, autistic, or broader community has had the opportunity to comment on, or indeed to resist.

It should not come as a surprise that this form of nation state exceptionalism appears to rely on tropes of autistic exceptionalism — the autistic workers in these programs are said to work at almost superhuman capacity. In her 2013 book Feminist, Queer, Crip, Alison Kafer argues that stories of the “supercrip” are what media finds most favourable, and are either the byproduct of low expectations towards disabled people or the fetishisation of “overcoming” disability to become worthy of non-disabled attention. I can picture the headline, and I shudder at the thought of an exceptional autistic subject being used to promote this national interest – “Autism Advantage Boosts Australian Defence”.

I also wonder if the supercrip figure is the most appropriate here, as it seems that representations of autism are moving ever further away from disability altogether. Perhaps it is the case that the pull of existing stereotypes of autism, which also lack disability informed politics, are so neatly aligned with national(ist) interests. Whatever the reason for this, and whether autism is positioned as disability or something else, autism is neatly positioned to become a tool for the nation. The use of autistic people and our supposed “comparative advantage” might have gained some autistics an occupation, but this is being used to facilitate Israeli occupation of Palestine, including deaths of tens of thousands of people in Gaza since October 7.

In light of the present overt tactics in national discourses to obscure and deny the genocide taking place, we must continue to resist divisions of all kinds within our communities, but especially where these divisions are premised on so-called “inclusion”. When the inseparability of disability justice from the end to settler colonial violence is not attended to, there is real and significant harm done. The Ro’im Rachok unit is just one example of that harm.

In order to demand justice and work in solidarity, the autistic community must pay attention to all forms of violence, inequity and oppression, particularly those founded in and enabled by settler-colonialisms. Refusing “inclusion” in the national imaginary, embracing “causing division”, sitting in the bad feelings that come with this refusal, are how we enact meaningful solidarity and build genuine coalitions across and between borders and bodies.

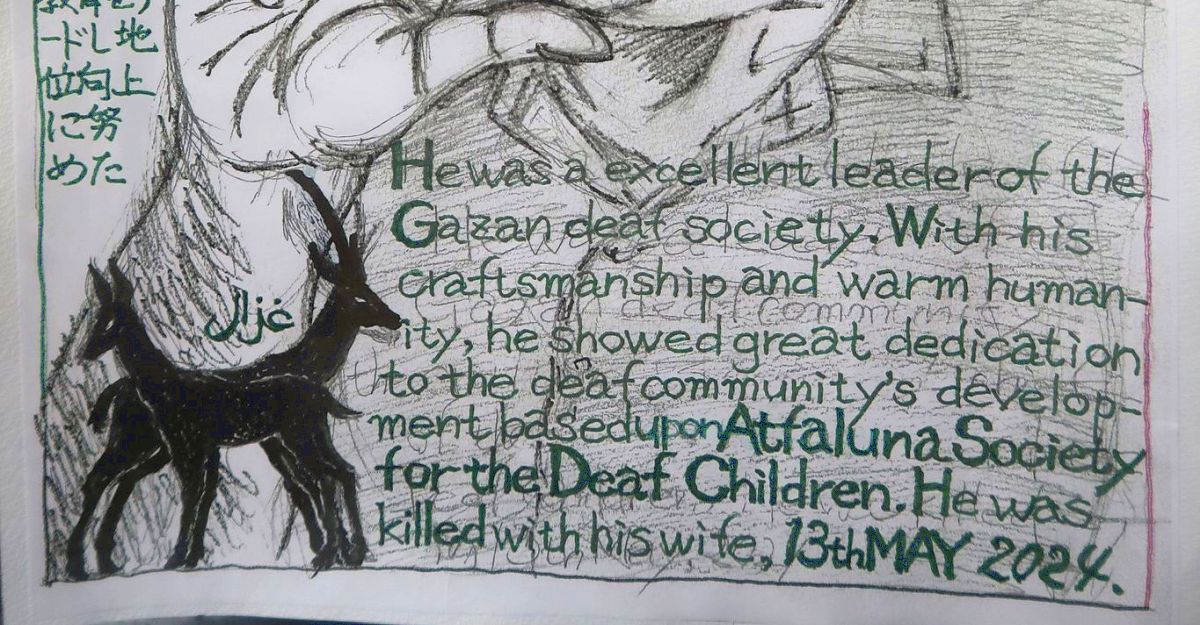

Image: Dale Mastin-Purcell