Schools are deliberate targets for government-funded mystification about Australia’s role in wars. Victorian Year 9 and 10 students, for instance, can enter three different government sponsored prizes about Anzac day, including the Victorian Premier’s “Spirit of Anzac Prize”. Primary school children have been recruited in the production of war memorial soundscapes and writing messages of thanks on dead soldiers’ graveside crosses.

Such instances of official remembrance crowd out the realities of war, and the consequences of Australia’s role in imperialism. As teachers, we should strive to resist this, and we should introduce our students to a fuller understanding of the history of the Anzacs.

Few students and teachers sitting through the annual Anzac ceremony, for instance, would associate Anzac day with Palestine — but the first Anzacs invaded Ottoman Palestine in World War I, and they took control of the land and the people for the British Empire.

After the armistice in 1918, Anzac soldiers of the Light Horse brigade remained in Palestine, waiting to be demobilised and sent home to Australia. During this time, some returned to the Gallipoli Peninsula, where they engaged in what was described as the “holy task of locating the graves of Anzacs, and in collecting trophies for the Australian national memorial collection,” solidifying the nationalist myth of the Gallipoli Landings, the anniversary of which was already being observed as Anzac day from 1915 onwards.

Such acts of quasi-religious myth-making about the Anzacs have continued to this day. In 2017, to mark the centenary of the Anzacs’ capture of Palestinian territory, then Prime Minister Malcom Turnbull and opposition leader Bill Shorten attended a commemoration service at Beersheba with Benjamin Netanyahu.

In his official address, PM Malcolm Turnbull stated that the Anzacs “like the State of Israel has done ever since … defied history and with their courage fulfilled history. Lest we forget.” His words are striking, not only because of the monumental historical narrative that they invoke (the Anzacs “defied” and ‘fulfilled’ history), but also because of the way in which they situate the Anzacs as “courageous” heroes who birthed two nations.

Turnbull was right to connect the Anzacs’ military successes with the creation of Israel. The Australian victories set in motion a series of devastating events, enabling the fulfilment of the Balfour Declaration, where Britain agreed, despite separate and contradictory promises, to recognize “a National Home of the Jewish people” to be located in Palestine, and the establishment of a “Jewish National Colonising Corporation for the resettlement and economic development of the country [Palestine].” In short, the British mandate was secured in part by the Anzacs, and this laid the ground for the creation of the state of Israel, while preventing the creation of a Palestinian state.

There are some other parallels with Israel that Turnbull did not draw. If both countries form their identities through stories of noble military successes, they both also hide a history of horrific, racially motivated violence against Palestinians. More than this, the brutal massacre committed by the Anzacs at Surafend chillingly portended the Nakba, the catastrophic displacement of Palestinians in 1947-1949.

Turnbull did not share this darker parallel because it did not suit the heroic myth-making project of the Australian and Israeli governments to do so. As teachers, however, it is our obligation to bring this history to light.

The Surafend massacre

Still waiting for demobilisation, the three brigades of the Anzac Mounted Division remained camped in Palestine, close to the Mediterranean, when, on the 10th of December 1918, a New Zealand soldier was shot after a bungled robbery and subsequently died. Convinced that Palestinians from the nearby town of Surafend were responsible for the murder, a group of vigilante Anzacs surrounded the town and demanded that those responsible be brought to them. When town leaders denied any knowledge of the events, the Anzacs cordoned off the town, refusing to let anyone leave.

Unsatisfied with how the matter was handled by army staff the next day, Anzac soldiers took their revenge. As noted in official accounts, “that which followed cannot be justified.”

Early in the evening, around 200 soldiers entered Surafend, initially expelling some of the town’s women and children. Armed with heavy clubs and bayonets so as not to accidentally shoot one another in the dark, the soldiers attacked the remaining townspeople. According to some accounts. as many as 137 people were bludgeoned and stabbed to death[1]. One eyewitness recalled “it was a most gruesome sight the manner in which their heads were bashed and battered.”

Anzac soldiers proceeded to raze Surafend to the ground. The flames from the burning town “lit up the countryside” and those nearby could “hear the shouts of the troops and the cries of their victims”. The soldiers then proceeded to destroy an outlying camp and murder its inhabitants.

Although a number of injured and maimed survivors of the massacre were treated in allied field hospitals and both the Australian and New Zealand governments paid recompense for the destruction of property at Surafend, no one has ever been held responsible. The exact details of the massacre were deliberately obscured and ignored.

In the words of Henry Gullet, however, Surafend “should not be forgotten.”

*

According to Palestinian scholar Walid Khalidi, the period of the British Mandate following World War I

as a whole, was seen by the Palestinians as an Anglo-Zionist condominium and its terms as instruments for the implementation of the Zionist programme; it had been imposed on them by force, and they considered it to be both morally and legally invalid.

In February 1947, Britain relinquished what it called the “problem of Palestine” to the United Nations. Australia was pivotal in the UN investigation and partition of Palestine that created Israel.

Recently, Israel has attempted to further legitimise its occupation through usurping and promoting the history of the Anzacs in Palestine, focusing primarily on the commemoration of the battle of Beersheba.

When the Anzacs captured Beersheba from the Ottoman Empire, in 1917, Beersheba had a largely Palestinian Arab population, as it did throughout the British Mandate. Beersheba was never intended to become part of Israel under the 1947 UN partition Plan. However, it again became a battle ground in 1948, when the city was captured by Zionist terror groups and its Palestinian inhabitants were terrorized into fleeing.

In 2007, the Pratt Foundation in Australia commissioned a statue for a theme park in Beersheba, erected in memory of Australian soldiers. Australia’s involvement in Palestine is etched into that statue, in the stone war memorials that are distributed across the Australian continent and in the Anzac soldiers who lie in Gazan graves. But the real legacy of Australia’s involvement in Palestine is to be found in Gaza, only forty-three kilometres from Beersheba, where Israel daily rains terror on two million Palestinian refugees, with Australian government support. This support is not only moral, it is also material: between 2018 and 2023, $13 million worth of Australian manufactured arms and ammunition have been exported to Israel. Despite Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s overdue calls for “an immediate humanitarian ceasefire,” Australia’s role as an arms dealer has contributed greatly and devastatingly to Israels genocide in Gaza.

In order to understand how such a complicity is possible, we must consider how we are all manipulated by the commemorations and the competitions which are trotted out each year on Anzac day. In order to prevent such a complicity in the future, we must show our students the past as it is, and not as our myth makers wish it to be. We must refuse militarism and turn towards the half-remembered graves of Surafend.

[1] Mulhal, A.S. In: Daley, P. Beersheba: Travels through a Forgotten Australian Victory. Centenary ed. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press, 2017

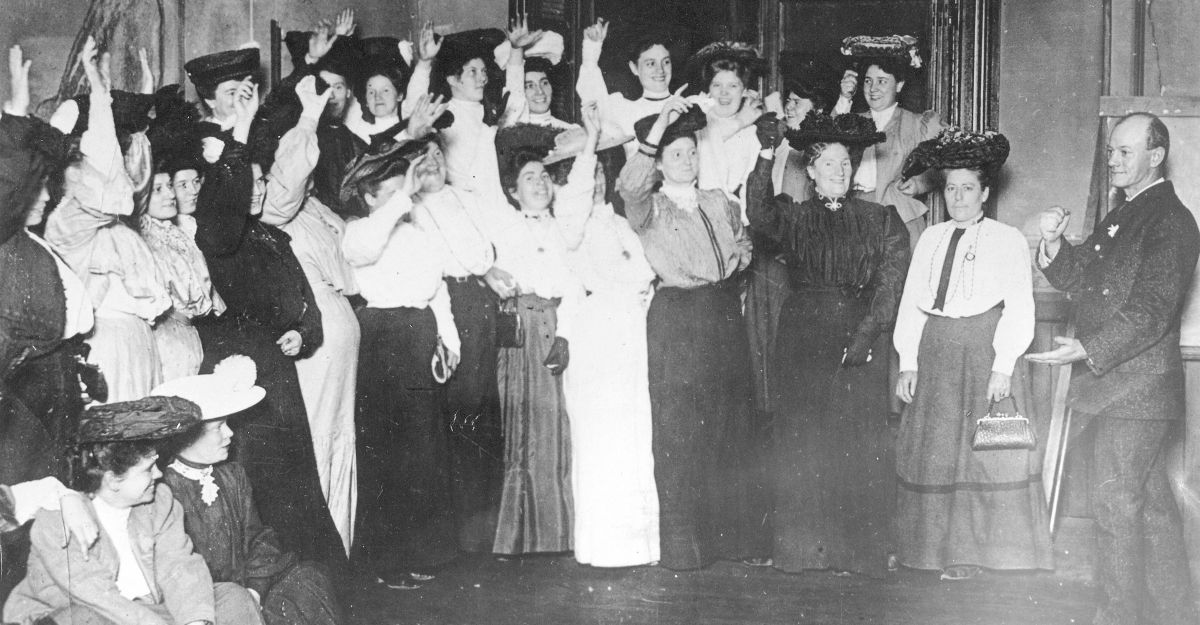

Image: Anzac Day, Jerusalem, April 25, 1940. General Freyberg and troops stand near the Stone of Remembrance. Wikimedia Commons.