What if we were to view a ‘no’ as something beyond the parameters of what the word seems to suggest? Within the logic of everyday myth, it has become somewhat of a cliche to argue that ‘no’ is a full sentence. I’ve been tempted, more recently, to see it as more generative than both word and sentence. Can it spell out better possibilities merely on its own? Maybe not. Could ‘no’ express a commitment to the other future, the one more serious, self-assured people insist does not exist? Yes. I believe it because when I hear the word refusal, I see the name Sinead O’Connor.

Articles, features, and obituaries of O’Connor all seem contractually obligated to mention her most famous act of refusal. It was on that Saturday Night Live in 1992 where she looked straight down the camera, wearing an old dress once worn by Sade, sang a cover of ‘War’ by Bob Marley, tore up a photo of the Pope, and killed the radio star — her career as both pop star and video star — to make it possible for her to go on living. The prevailing assumption was that it derailed her career. She, however, felt that she had nothing left of her own to lose; to her, it had the opposite effect.

Sinead died earlier this summer, but it had been a long time since the moment that Sinead the pop star had been effectively left for dead. It was as if each moving part of the culture had a hand in it: on this point, neither the artist herself, the industry, the press or the people could have disagreed. But to no longer live as a pop star, and to reject its schema, was to finally become something else, something greater: a talking, thinking, real human being.

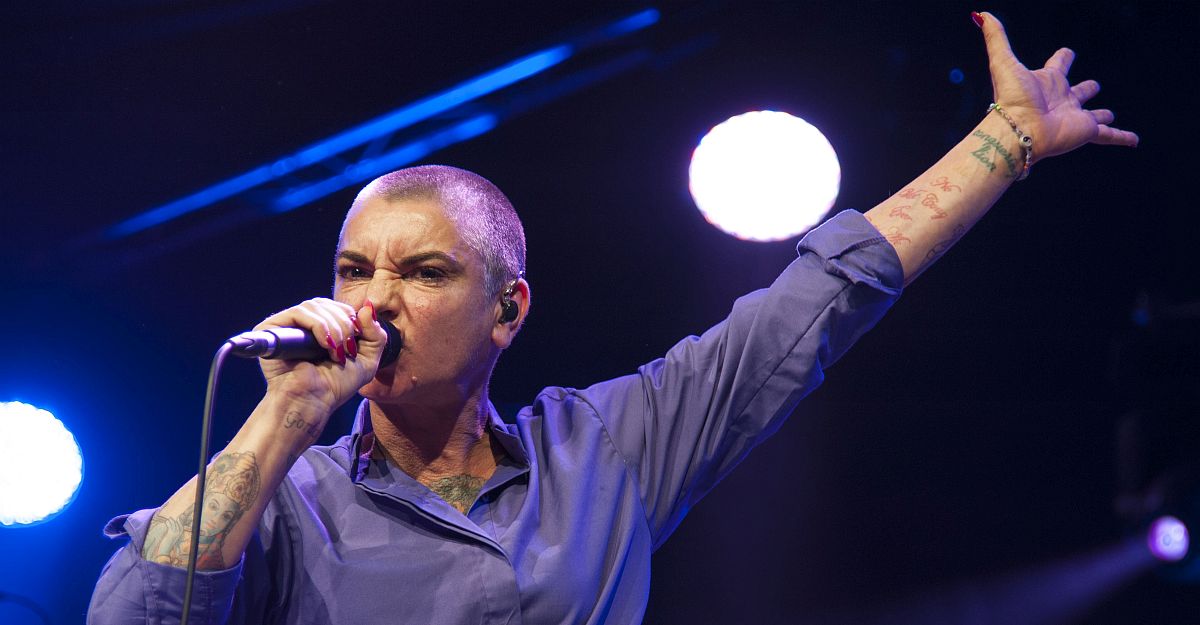

To be a still image is vulgar work. To have your likeness smoothed over, unruliness being the thing that can obstruct the kind of clean, effortless delivery we have come to expect between producer and a consumer — it’s no way to live. Sinead’s whole career was an experiment in coming up with new ways to rebel against this dictum. To be a worker and artist instead of a brand meant knowing ‘the difference between production of a market commodity and the practice of an art,’ to quote Ursula Le Guin. Maybe no one in recent pop culture history had more clearly known that difference. She lived it.

Sinead’s ability to quickly identify those constraints and to unseat them was legendary, yet seemed highly disturbing to others, a failure ‘to adapt.’ When one is expected to freely give their entire selves up to be sold, going along with it without question, it chafes to see someone else succeeding in spite of that shared, often unstated expectation. Sinead O’Connor acted on what was just rather than what was cynical or convenient, rarely shying away from the likely (possibly even inevitable) consequences. Some call this fortitude.

The SNL moment being even bigger than the person who created it is somewhat of a problem. A viewer at the time might have been drawn to the abruptness of the action itself, thereby de-emphasising all else. A viewer like me, watching it on YouTube as a teen, lingered instead on the deeply human expression immediately before the performance, and then those vanishing seconds in the after, where she is seen doubling back. She checks to see if all the candles had been blown out. The camera keeps rolling, as if the operator is in shock. Eventually the screen fades. Here, no trained flourishes or choreographed movements are perceptible, though her unique gait is. I recognise it so clearly in her, because it lives on within the posture of the no-bullshit proletarians I know and love, as a seemingly contradictory twin flame of meekness and recalcitrance. Living this way is only intensified by its resistances. If to be scripted was unthinkable, to act on your own terms is only natural.

Sinead’s appeal springs from this unruliness, this reticence in adhering to the mores of civil society — ones that I have found, over time, to determine the nature of one’s personal progression more than the actual quality of one’s work. Her disinterest in following a script, law, or party line is a signal to those who are like her, to the real ones who might get it, whether or not it was intended. Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers recognised it. When she died, he said: ‘for all us street kids, all us wildlings, when she became huge, it felt like one of us had made it.’

My favorite example of this sensibility comes from a correspondence between Sinead and a friend of hers, writing to her to check in with a ‘how are you going’ message, to be met by the response:

I’m OK … strong little cuntress.

Of course Sinead wanted conventional success, at least at first: it’s undeniable. In ‘Daddy I’m Fine,’ a song from one of her most eclectic and underrated albums, she revisits the scenes of her early life, her hopes of ‘being a big star,’ ‘not going to school no more,’ ‘looking cool,’ ‘looking good,’ wearing ‘black leather boots,’ doing her ‘hair and makeup right,’ and ‘fucking every man in sight’ (the ideal Friday night itinerary). But she never wanted that stardom for its own sake. The real reason for Sinead’s idealism was a hope for escape, the imagining of a dream life beyond mundane suffering. She soon understood the contract was flawed. ‘It seems to me that being a pop star is almost like being in a type of prison,’ she confided in 2021 to interviewer Amanda Hess in her last major profile for The New York Times. ‘You have to be a good girl.’ To imagine success was to imagine an individuating force, something of her very own — which could have represented anything — whether it be a means to get closer to herself, to others, or the power to define her own version of success outside of all the others.

As far as success is concerned, Sinead created many versions of it, defining it in her specific, unique shapes, interpreted even more interestingly by all who witnessed her. One person’s idea of Sinead was a demonstration of a real multi-genre collaborator and true believer, working intuitively across the forms that resonated with her at the time, rather than being a culture vulture or commodifier as the market/label/manager demanded. Another version of Sinead showed what true integrity could look like outside of a provided script, how honesty was more vital than following, or anxiously predicting, trends. Yet another version of Sinead displayed how artistic vision, ambition, and individuation could come before mere material gain. It seems remarkable that such an uncompromising, singular person, sometimes recognisable only by a snapshot, could live so large in her own way, be so incredible outside the limits of objectification so as to be deeply varied.

As a young person finding her music haphazardly, returning to subsequent albums at somewhat unpredictable junctures — which only her highly idiosyncratic output could properly speak to — I found her ability to reject ‘the good life’ and traditional ideas of success almost dangerously thrilling. This still rings true. Sinead’s ability to reject ‘success’ by standards other than her own seems even more desperately impossible now than it has maybe ever been. These days there is very little wiggle room for working artists to make a good living. The emergence of reactionary thought in response to these conditions reflects a deep lack of imagination — an inability to form new alternatives to capitalism (with the limited ‘options’ as Jamie Hood puts it, often ending up to be ‘Janus faces of the same coin’). It seems undeniable, now, that the only way out of precarity — at least, the one that I’d presented to us — is to burrow deeper into the exact same fraught systems that we might have once sought refuge from.

Some of our biggest pop stars represent this sense of entrapment. Some continue to work with male producers known to abuse other women. Now, not selling out is functionally impossible, a way to mark oneself as a killjoy in the economy of yes men. You need not state your principles out loud for them to be near intolerable to the psyche of others. But it is helpful to know that within the framing of the killjoy, as Sara Ahmed argues, ‘there is an agency that this dismissal rather ironically reveals.’

What we find within Sinead’s work is an antidote: there is always another avenue. Reaching for it when no one else can imagine doing the same is a rebuke. It is seen as infringing on others’ territory, on their right to craft their own reality, basically unforgivable, even ‘insane’. Those exact words were thrown at her, among many others. To quote from a comment in her NYT profile: ‘it was like there was open season on me being a crazy bitch.’ Indeed, now, as Catholic archbishops are named for the abuses they covered up, the champions of neoliberalism discredited, and abusive men in the music business are gradually exposed, we collectively say that Sinead was ‘ahead of her time.’

It is not incidental, to me, that we are awash in cultural products that insist we accept what is on offer – the specific nihilism of remaining staid regardless of how limited our lives stand to become. It is totally unsurprising that this belief is so widely proliferated at a time where organized labor is similarly coalescing, explicitly rejecting those terms in pursuit of a better deal, as Lexi McMahon has pointed out. In many ways, Sinead prophesied those ways of thinking, and resisted forces we now identify as noxious and inalienable — those fears of an alternative, taking the form of works that may not have been commercial, but did something more admirable: the furthering of an idea. She was not just human or artist but a kind of saint for those who embrace rejection. That need not be seen in the language of deficit: it can be a way to test the boundaries of the social contract and believing in what Sinead wrote:

I know my scripture. Nothing can touch me. I reject the world.

Image: Wikimedia Commons