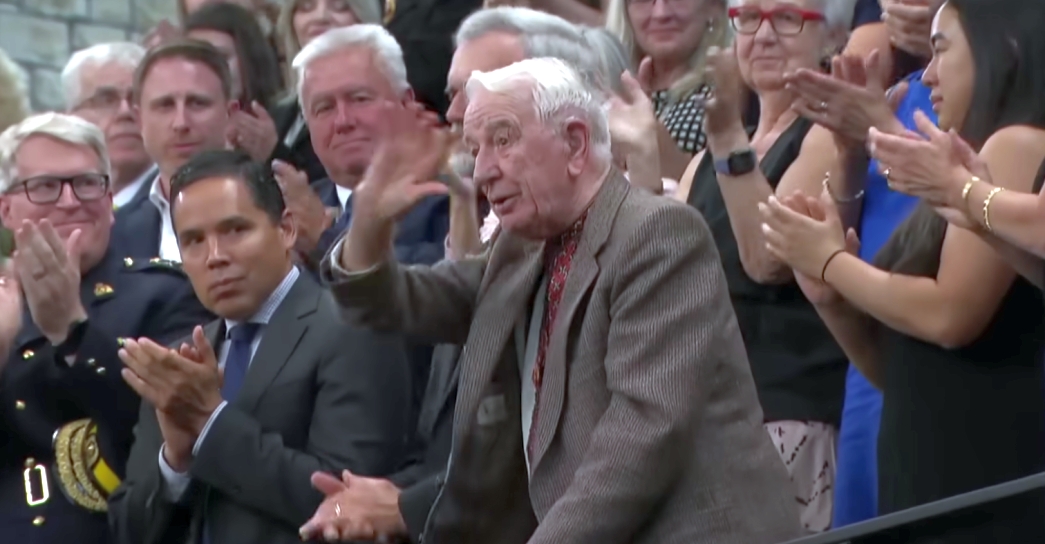

On 22 September, during a visit to the Canadian Parliament by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Speaker Anthony Rota publicly introduced ninety-eight-year-old Yaroslav Hunka as a constituent ‘who fought for Ukrainian independence against the Russians’ as part of the First Ukrainian Division during the Second World War. He was ‘a Ukrainian hero, a Canadian hero, and we thank him for all his service.’ Hunka received a standing ovation from all present.

This scene was reported two days later by an antifascist site on Twitter, who pointed out that the First Ukrainian Division was also known as the Waffen-SS Galizien Division. Canadian academic Ivan Katchanovski linked to a veterans’ webpage in which Hunka wrote that he had been a volunteer recruit to the Galizien Division in 1943. Hunka had also uploaded photographs showing him in uniform with the ‘boys’.

The Kremlin immediately reacted, with spokesman Dmitry Peskov arguing that ‘such sloppiness of memory is outrageous.’ Opposition Leader, Pierre Poilevre, described this incident as the worst diplomatic embarrassment in Canada’s history. Rota resigned, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was forced to apologise unreservedly.

These embarrassing episodes continue to occur in countries that resettled the post-war displaced persons of Central and Eastern Europe. This mass of around one million people had refused to return to homes that were under Soviet control. As well as concentration camp inmates and forced labourers, these political refugees included soldiers who had fought in German military units, as well as civilian collaborators. Security screening was difficult and there was also some sympathy from the Allied military authorities for veterans on the losing side. Whole cohorts were resettled in Britain, including 8,000 Ukrainian members of the Waffen-SS Galizien Division. Ukrainian nationalist declarations were also treated seriously. While all Ukrainian displaced persons held either Polish or Soviet Union citizenship, they were treated as a separate group quite quickly.

Many of these men should have been charged with war crimes. The German-led Holocaust had relied on the firepower and administrative skill of non-German Central and Eastern Europeans, including Ukrainians. Ukrainian anti-Soviet and anti-Polish nationalists were initially involved in individual and group paramilitary acts, including voluntary local pogroms and/or acts of murder before or beside the German occupation. One of the pogroms, which involved the massacre of 12,000 Jews, was named Aktion Petliura after the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura, who had been assassinated by a Ukrainian Jew (this assassination itself framed as retaliation for earlier pogroms) in 1926.

After the initial wave of pogroms, Ukrainians became progressively involved with an institutionalised German genocidal machinery. Ukrainians joined a Ukrainian Auxiliary Police Force (Schutzmannschaft), the German security police (Sicherheitspolizei, SiPo) and the intelligence agency (Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS, SD). Others hunted Jews in their forest warden jobs. Local policemen were empowered to kill anyone the Germans defined as enemies of the state, including Jews; indeed, the Germans relied on the dramatically increased numbers of local forces to do the dirty work of the Holocaust, including the shooting of children. Between 1941 and 1944, 1.6 million Jews had been murdered in Ukraine. In 1943, 100,000 of these men volunteered to join the Waffen-SS Galizien Division. In this capacity, they have been accused of murdering Polish civilians.

The United Nations’ International Refugee Organisation resettled the displaced persons in the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The western world was eager to use the labour of these healthy, white, and stridently anti-communistic young men. Australia resettled 170,700 displaced persons including Poles, ‘Balts’ (Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians), Yugoslavs, Ukrainians and Hungarians. There was immediate criticism by Jewish groups and sections of the press that the new migrants included war criminals but these were roundly dismissed as Soviet communist propaganda.

Decades later, all four of the main resettlement countries instituted judicial processes against the alleged perpetrators of the Holocaust who were now resident in their countries. In Australia, such men were guaranteed a fair criminal trial: the evidence, for crimes that occurred over forty-five years before, had to include documentary and material evidence and, ideally, eyewitnesses to the alleged individual perpetrator carrying out a war crime. Of course, the nature of the Holocaust was such that very few eyewitnesses to genocide survived in order to testify against individual killers.

After a flawed investigative process, only three men were charged. All three were Ukrainians who had resettled in Adelaide. Ukrainian auxiliary policeman Mikolay Berezowsky was accused of being party to a mass murder of 102 Jewish villagers. Henry Wagner, an ethnic German liaison officer between the German and Ukranian auxiliary police force, was charged with being party to two mass murders, including the shooting of nineteen part-Jewish children. Forest warden Ivan Polyukhovich was accused of hunting and killing Jews under the German occupation, and in taking part in a mass shooting. However, the evidence bar was so high that there were no convictions.

Immediately after the unsuccessful war crimes trials, Ukrainians again attracted attention with an award-winning novel by Helen Demidenko, purporting to be written by a Ukrainian-Australian and based on the life story a member of that community. To the great embarrassment of the Australian literati, Demidenko was soon unmasked as English-Australian Helen Darville, who had attended the Polyukhovich trial with a young man who was noticed to be repeatedly muttering ‘Jews’.

Many responses to Ivan Katchanovski’s tweets shedding light on this unsavoury history — one that Canada and Australia share — claimed that this was not the time to be critiquing Ukraine or Ukrainian nationalists. Ukraine was, of course, invaded by Russia in 2022 and that war is ongoing. Most in the West sympathise with, and support, Ukraine’s fight. And Russia has attempted to smear all Ukrainians with accusations of Nazism, which is simply not true. Dismissing inconvenient histories and the problematic pasts of individual migrants to both Canada and Australia, however, is not useful. The complicity of the West in assisting perpetrators to escape justice should be acknowledged, and we must be wary of any attempt to normalise fascist views and actions in the public sphere.