I’ll start with my truth. I was born in the early sixties in rural NSW to a Wiradjuri family. And I’m voting Yes to the enshrine the Indigenous Voice to Parliament. But truth does not rate highly in this nation.

I am one of these Aboriginal people who are offensive to conservative opponents of the Voice. I grew up in a house with ten other people as part of a large extended family. Both my parents worked in unskilled labour and neither were educated beyond the age of fourteen. I managed to finish high school and was lucky enough to benefit from Whitlam reforms and get a free tertiary education in the early Eighties, which allowed me to secure a professional job, and later go on to further post graduate studies. I own a home and have a well-paid job. These truths are objectionable to right-wing media. But then again so are many truths of this nation like invasion, frontier massacres, stolen children, over policing, and commodification of Aboriginal lands and waters.

According to the commercial media outlets, supporters of the Voice—the Yes Campaign are continually criticised for not getting their message across; or that the message is not clear. The approaching referendum question proposes To alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. I’m not sure how much clearer the message can be. But the constant echo from the commercial media promotes a narrative of not selling the message. It’s the sell then—the commodification of information that dominates here, rather than the socio-cultural values at the heart of the message of the Voice.

A good question is: should you really need to sell a simple, yet powerful truth. Apparently so, according to the opponents with their emphasis on risk and loss. Their campaign seems to be fuelled by what they perceive Australians will lose and the fear of what is at risk.

The conservative No campaigners represented mainly by the Coalition and Fair Australia have a plethora of narratives to sell ranging from such things as—an enshrined Voice will threaten people’s backyards and properties. Aboriginal people will be in charge of parking fines, will seek compensation claims running into the millions, will control executive government—thus influencing and interfering with government decisions on such things as the AUKUS agreement, or open up legal challenges to the high court, interfere in government departments, control the Reserve Bank and interest rates, open the door to activists, and abolish old colonial institutions and traditions such as Australia Day. This camp uses the word division and divisive continuously, implying that to date Australia is a united, and equal nation for all. Using such words as a mantra plays on emotion and fear at the expense of ethics and logic.

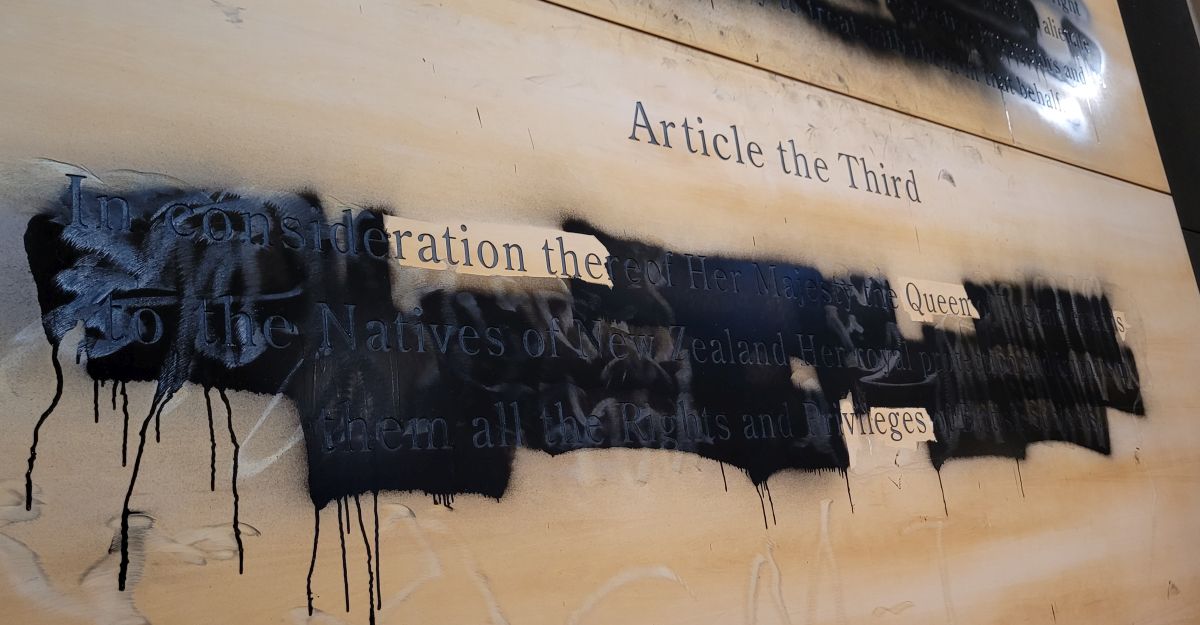

Then, there are those who call themselves the progressive Nos represented mainly by the Blak Sovereign movement. This camp opposes the Voice arguing that it does not go far enough, that it is tokenistic, that it is window-dressing, and that it will impact on Blak sovereignty—and that First Nations peoples should reject and, in some cases, overthrow the constitution not work within it.

It is not hard to notice that these two No camps are contradicting each other. One claims that the Voice will impact on and interfere in every aspect of Australian life and pose a threat to existing colonial institutions. The other argues that the Voice will do nothing, is not strong enough, does not go far enough and advocates for the rejection of colonial institutions such as the constitution. One side sees itself as conservative right and the other radical left.

But extreme politics does not sit at opposite ends of a straight line, however much its proponents like to think it does. Extreme politics bends like whalebone until two opposing ends meet. The conclusion that both these camps are arriving at is exactly the same—vote NO. What’s really scary in all this is that however radical the progressive No camp argues that they are, their NO vote on polling day will be supporting and emboldening the conservative NO position advocated by the Coalition. These two letters, N-O, look exactly the same on paper in an anonymous ballot. The progressive NO voters are making the Coalitions job of blocking the referendum easier.

To illustrate this point, recently a First Nations speaker addressed the National Press Club in Canberra. This speaker is also a prominent advocate of the No campaign. They spoke very passionately and movingly of what settler colonialism has done to their Country and their people and of the intergenerational trauma that is still unresolved. Andrew Bolt took aim at this speech shortly afterwards and excepted parts of it for yet another one of his right-wing rants. This is no surprise—unfortunately we’re used to Bolt.

What’s poignant though is that Bolt’s disciples took to X/Twitter and responded thick and fast, re-posting excerpts of this speech, refuting the truth of it and all resoundingly ending their mini-bigoted spiels with the words Vote No! Do you see the irony here? The person that the Bolt-clique are all shouting Vote No in response to is also voting No. Irrespective of the narratives offered to justify each camp, all those NOs will all translate the same.

In a recent interview with the ABC, a young palawa voter commented that there were three camps in the lead up to the referendum. One united Yes camp; and two No camps. They described themselves as a passionate Blak NO. This is a fitting description of the progressive No. The other NO is the conservative obstructionist one. But while the two ideologies are poles apart, this difference will not translate in the referendum polls.

The last time a referendum was held in Australia was in 1999, on the question of whether the country should become a republic. Only Australians who are now aged forty-two and older would have voted. When October 14 rolls around, the Voice to Parliament referendum will be millions of Australians’ first.

John Howard was the Prime Minister in 1999 and he was opposed to the idea of a republic. He said he was voting No because it wouldn’t make the country better off under the model proposed and that there were ‘enormous benefits to the current system.’ Howard managed to split the support for the republic by writing a preamble to the republic and arguing that it should also appear in the constitution.

Australians were asked to vote Yes or No on altering the Constitution with two amendments: the first was ‘to establish the Commonwealth of Australia as a republic with the Queen and Governor-General being replaced by a President’ and the second was whether to ‘alter the Constitution to insert a preamble.’

Polls throughout the 1990s regularly recorded voters favouring a republic by roughly two to one, albeit with a quarter undecided. But many people who thought the model for a republic being proposed in 1999 was unsatisfactory voted No, as did those who argued that it wouldn’t change anything significant. Former PM Bob Hawke noted that it was clear that a majority of Australians wanted a republic but there was confusion about the model.

Republicans wanted Howard’s preamble to fail, despite wanting Australia to become a republic. I remember the 1999 referendum clearly, and what emerged was that many voters were under the impression that—given the overall support and momentum for a republic—they could afford to reject this proposal and vote for a better model in the near future.

That was twenty-four years ago, and successive Labor and Liberal prime ministers have said they would not revive the republic debate, meaning that it is unlikely to be revived in the near future. Referendums are one-shot opportunities for the nation to make a choice on which path it wants to take for the future. If the opportunity is voted down it is not offered again. If the Indigenous Voice is voted down, it is highly unlikely that it will ever be offered again. It is also impossible to live outside of the constitution or to overthrow it.

If we are to believe the polls, it is the older generation, the boomers who are posing the greatest opposition to the Voice. Peter Lewis from the Guardian commented in translating the latest essential poll that if this referendum were to be decided by 18-35 year olds it would be a ‘slam-dunk’. In 2021, almost a third of the Australian voting demographic—31%—was aged 18-35 years. This is the demographic who will have to live with the outcome of the referendum.

The Voice referendum is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for the younger demographic to shape the future of the nation. Future generations of younger Australians will have to live with the outcome of October 14 for quite some time. If the referendum is defeated, it means a nation was given the opportunity to recognise its First People and refused it.

At the end of the day it is just you and your conscience in the ballot box. It is your opportunity to shape the future. Think not just about what kind of a nation you want to live in. Ask yourself what kind of Australia you want to leave for future generations.