I first heard of Jen Craig when she was interviewed by Michael Silverblatt on his KCRW radio program Bookworm. Her novel Panthers and the Museum of Fire had found publication with the American publisher Zerogram Press. There was some talk of the influence of Thomas Bernhard and WG Sebald, the difficulty of making a sentence and spinning a clay vessel on a wheel—a shared problem of concentration and balance. When I tried to find her book here, I could not—but now Panthers, alongside the slim 2010 volume Since the Accident, have been reissued with Puncher & Wattmann, who have also published her third book Wall.

If Panthers was named for an incongruous road sign on the side of a highway, Craig’s newest novel is also titled after an object of obsession for its narrator. The narrator in Wall is an artist, and she conceives of the Wall as a project—an object, a piece—that would represent her experience of living with anorexia. She recalls the problem of this failed, and unfinished, artwork after arriving in Sydney from London, where she has returned to clean out her father’s house after his death. Finding it crammed with hoarded objects, she considers recreating Song Dong’s Waste Not, which would catalogue and display every object in the house: it would be the Chatswood Song Dong Project. Wall, the novel, takes the form of a letter, or monologue, addressed to her absent partner Teun.

Much could be made of this set-up, yet in Craig’s book all these activities, relationships, and events occur elsewhere and offstage. The book demonstrates that it is uniquely free from the kind of well-meaning, but essentially arid and over-plotted fictions that clamour for attention in the market. What is striking is the attention given to the actual page: the careful composition of, say, a paragraph of prose. What happens in Wall is activity at the level of language, its rhythms and repetitions, rather than through the mechanism of plot. You can see the considerable effort of making the page, as a unit, operate well enough on its own, even though it is offered in service to this long and singular utterance.

Comparisons, like those made by Silverblatt, with the works of Bernhard and Sebald are inevitable, but Craig can also be associated with contemporaries such as Lucy Ellman and Claire-Louise Bennett. The lash of Bernhard’s sparkling tirades, the rude quick-wittedness of Bennett’s wily sentences; these are writers whose books seem to pour forth from their opening salvo. Which is to say, what happens in Wall doesn’t matter ever so much as what it exhibits, and Craig’s opening line demonstrates the textual tendencies to come:

I need to tell you that once I’d given up on the idea of turning the contents of my father’s house into a vast and meticulous installation in the style of that famous artist Song Dong, it just took me getting the call from City Hire Skips as I was walking down the hill from the ridge where I was staying – this call that confirmed the bin would be arriving from one pm – to make it seem, suddenly – magically – as if the entire house were already clear of the junk and disintegrating remnants of more than fifty years of abject living, and that now there were no more distractions keeping me from the Wall.

And from there the voice goes on.

Wall has a certain temporal slipperiness that it shares with a book like Woodcutters, as things said and done long ago crowd in on the dialogic present. Bernhard returns us repeatedly to certain themes —Joana’s death, the premiere of The Wild Duck, the wing chair, the dreadful city of Vienna, the Ausbergers’ artistic dinner, a terrible funeral goulash—to rope us in and tether the narrative down. Wall exercises a similar obsessive repetition: Song Dong’s Waste Not, the meeting of Nathaniel Lord in Hackney, the awful tarpaulin, the leavings of her father, the ‘Still Lives’ project, and the art school happening recur every couple of pages.

Yet in Wall there is an absence of glittering scorn, and it means the narrator lacks a certain kind of density; her protagonicity—for want of a better term—has a deteriorated quality, as if the narratorial heft we associate with Bernhard requires a certain degree of bitterness. The major and minor points of disgust and disdain, such a propellant for the incandescent rantings in his work, here prompts a fluttering nervousness. It is anxiety, worry, and guilt that agitates the novel’s progress, all the while circling back to conversations, meetings, and events that prickle at the narrator’s conscience. As readers, we are at risk of getting lost in this tightly composed text. It is a text that neatly describes itself well, and the narrator’s explanation of her artist practice provides a decent sense of how the novel feels:

Yes, this very driven way of working, as well as that tendency of mine to ignore everything else in my life for the time that I am working on whatever I’m working on – and becoming anxious – churned. Tied into knots by the inevitably tight-winding ways of my peculiar practice.

Grace Paley has talked about reading her stories aloud, to hear their pace and speed, for getting a feel of where to slow the reader down: ‘The eye goes zzt, zzt, zzt, you know? The ear says, ‘Wait!’’ There is a vivid life-fullness in the narrative voice of Wall. It is a voice that starts to gush and overflow, all the while slowing itself down. The narrator is constantly hedging and deferring: ‘I need to tell you’ … ‘as you know’ … ‘as you know very well’ … ‘as I said to you’ … ‘as I’d got the feeling’ … ‘I remember saying’ … ‘in fact’ … ‘and really’ … ‘and so’ … ‘and so, yes.’ The form promises that we might hear the whole thing straight, yet we don’t. The telling is delayed by the retelling, and the redoing of sentences and clauses, as if trying it out again for pleasure, for getting the mouthfeel right. A taste:

And of course, nothing in this exhibition was disgusting to me. It was surprising, I said, because not a single bit of the exhibition had been disgusting in any way at all.

or:

Yes, this apparent giving in to what had seemed, at the time, to be so fashionable and yet so entirely relevant and convincing way to see it all. Relevant of course – entirely relevant – but also way off course from what it was that we had been thinking then, if we had ever been able to name what that particular thing was.

The allure of matter is a preoccupation: junk, belongings, leavings. Sentences are built out of things said once, mistakes made, conversations missed or lost. The monologue takes everything into itself, and repetition is a way of chewing it over again. For such a slim volume—not quite two hundred pages—the scope is immense. To reach for an equivalence between hoarding and sentence building in Wall is tempting, however Craig’s project—and her narrator’s—seems closer to that of disciplining excess.

The long sentences accrue in a wayward fashion, a bit errant and a bit roguish; they give the impression of being out of control, but aren’t. Each sentence bears down on the one that came before: the wings are clipped, a corrective offered, and the screw of the sentence well tightened. Although here and there the voice might waver a little, Wall is by no means uneven. Compression is key, and Craig’s novel is as tight as a drum.

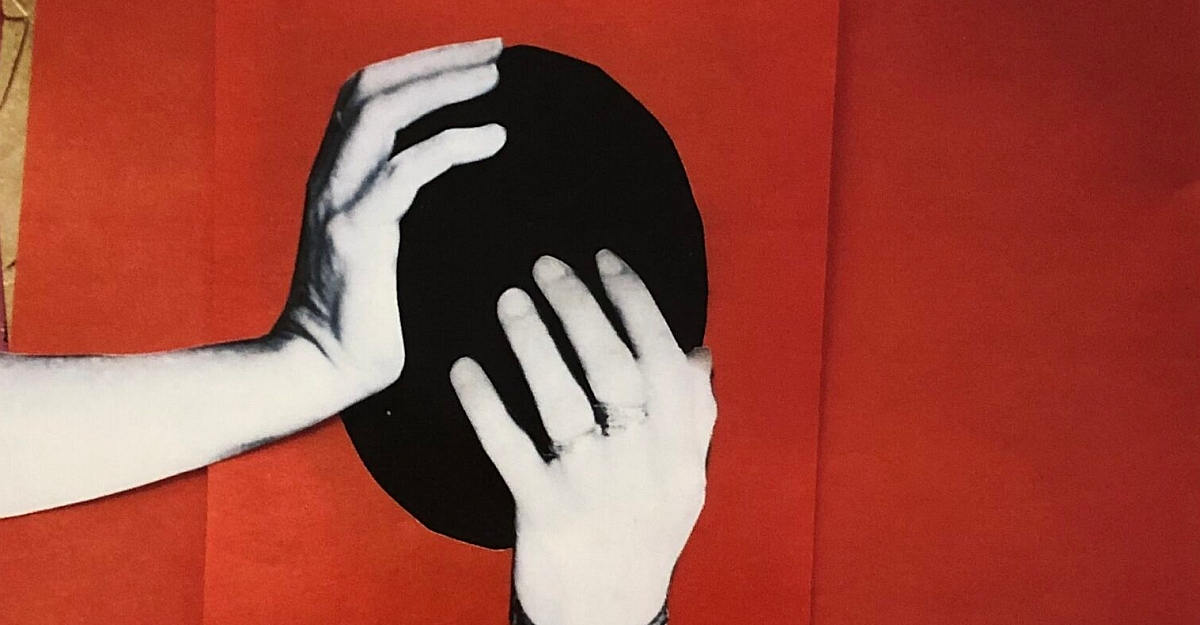

Image: a detail from the cover of Wall