The dawning of the COVID era in the first months of 2020 required a sizeable perceptual shift. At that time it was collectively difficult, even surreal, to conceptualise the idea of a global pandemic, though many of its effects manifested as an acceleration of pre-existing conditions. For those of us suddenly afforded copious amounts of time alone to process this shift, the rise of ‘COVID literature’ was swiftly inaugurated as both marketing buzzword and genuine tool for grappling with the broader consequences of current events. Everyone seemed to have their pick for a topical timekill in lockdown—friends began rereading Ling Ma novels, morbidly streaming Contagion, or DMing me eerie parallels with post-plague fascism in V for Vendetta. I was also trying to think of my own relevant cultural precedent, a way of being present with the new collective reality while also accepting the mandate that IRL circulation was out of the question. I wanted something that wasn’t social media, or the news, but which also felt useful, immersive, consuming.

By the time the second and definitely more intense-feeling episode of Victorian lockdown was beginning, I thought I had found it in the complicated cult classic Bad Boy Bubby (1993). The title character is raised by his abusive mother in a nuclear bunker until, at the age of thirty-five, he escapes to find the outside world is not the dystopian wasteland that he (and the viewer) understood it to be, but suburban Adelaide in the 1980s. The pandemic was maybe like a reverse of that? But as the months progressed and restrictions tightened further, my DMs slowed, and I began to feel the psychosomatic fraying resultant from being basically alone for weeks and months on end. I forgot about the film, which occupied only a single evening, and found myself returning to another text which spoke to the indigestibility of the advanced moment, a nineteenth-century work by Joris-Karl Huysmans called À rebours (1884).

The book describes an evil French aristocrat, the Duc Jean des Esseintes, who spontaneously retreats from his urban life to begin an existence of near-total isolation in a house on the outskirts of Paris. The title literally means ‘against the forward direction’, but in translations is given as Against the Grain, or more often, Against Nature. Such is the framing of the narrative, supplanting an earlier title of Seul (or Alone), where des Esseintes’ choice to purge his life of people and populate it instead with objects, books and artworks is cast as wilfully perverse, an acceleration of mediatised experience that goes beyond the natural order of things. His robust sense of himself as an connoiseur achieving the solace to pursue his manifold aesthetic interests soon gives way to something like content-saturation—it begins to poison him, his mind refusing ‘to absorb any more’ (102). People who have been through a months-long period of pandemic-related isolation may recognise this psychological trajectory:

He lived on himself, fed on his own substance, like those hibernating animals that lie torpid in a hole all the winter […]. At first, it had nerved and stimulated him, but its later effect was a somnolence haunted by vague reveries; it checked all his plans, broke down his will, led him through a long procession of dreams which he accepted with passive endurance without even an attempt to escape them. (102)

Not in search of lost time by any means, des Esseintes finds himself in the thick of it, glutted, with the cord imperfectly severed between his former life and current solitude.

The ‘unnatural’ quality of this experience of isolation is exacerbated by the fact des Esseintes chooses to prolong it, even in the face of deteriorating mental and physical health. It seems like there is no choice: he would do anything but return to the filthy metropolis and its crass, violent, sickly population. Blending moral asceticism with moral aestheticism, des Esseintes articulates a personal philosophy that objects not only to the social ‘promiscuity’ of Paris, but equates this with a debasement of art, literature, and lifestyle which anyone proximate is inevitably exposed to. It’s all too human somehow—he would rather be immersed in his own private world, in which the guiding principle for aesthetic value is an extreme, rarified artificiality that supersedes ‘natural’ or ‘ordinary’ human experiences.

Much of the text is a demonstration of this philosophy, beginning with the furnishing of a creepy, purpose-fitted isolation mansion. Its walls are painted in colours chosen for their appearance in candlelight—des Esseintes having of course become nocturnal—dominated by orange, ‘that irritating and morbid colour with its sham splendours and acidic feverishness’ (48). To make double-sure that minimal natural light can enter, the windows are set with thick bottleglass, including a dining room ‘porthole’ further separated from the external window by an aquarium filled with robotic fish. It casts greenish shimmers and, at sunset, when des Esseintes gets up to begin the day, ‘fiery gleams like glowing embers’ (52). The artificial mise-en-scène is completed with maritime lithographs and maps, a collection of salty fishing rods and ropes in one corner, and even sprays of fresh tar, allowing des Esseintes to simulate the sights and smells of a long sea voyage without ever having to leave.

The assonance with stircrazy families camping in their yards during the pandemic is significant, part of why I see the novel as being so COVID. The huge historical time gap between its writing and the current global situation (and even the common parallel with the 1918 Spanish Flu outbreak) is remarkable in that it is able to connect the late-capitalist viral crisis and industrial-revolution-era aesthetic perversity. If the pandemic has accelerated existing conditions, it traces a partial lineage for some of those conditions, namely, the hostility between colonial and capitalist industrial development and the vexed but powerful forces of nature. Jens Lohfert Jørgensen’s reads des Esseintes’ haughty disdain for conventional living as a ‘bacteriological’ response to the disquieting nineteenth-century revelation that germs are in fact everywhere. Even if no literal virus reigns outside, des Esseintes’ fastidiously-orchestrated separation from the natural world is such that aesthetically artificial ‘lifestyle choices’ align with the sometimes counterintuitive and elaborate medical hygeine practices required to mitigate infection, at a time where these protocols were first being formulated.

The irony is of course that the psychological, physical and even spiritual costs of des Esseintes’ precautionary living surpass its perceived benefits—a halo of illness seems to surround every facet of his life, and every attempt to escape the primacy of nature. It is present in the dining room, where the artificially-enhanced light contributes with the intense aromas and textures to give an effect of a journey not just to a foreign country but into the underworld itself. Synesthetically, the dazzling, fiery embers cause the simulation to err into hallucination, a pattern that is repeated throughout the book as des Esseintes grapples with unnameable psychosomatic and chronic health conditions.

The superiority of des Esseintes’ aesthetic directives is undercut by mounting evidence against their overall ‘healthiness’, as when it becomes clear, for example, that the dark, desiccated rooms of the mansion cannot seem to support any forms of life other than that of their owner. One chapter details a lengthy attempt to fill the house with rare and exotic plants, selected for the appearance of being man-made, and so aligning with des Esseintes’ anti-natural ideal. Waxy anthuriums, paint-splattered calladiums, even an amorphophallus, are brought into the house only to perish shortly after arrival. He also purchases a giant tortoise and, being repulsed by its dull, earthy carapace, has it gilded and inlaid with precious stones. He finds it a few days later, terminally halted in its glacial wandering across the floral rugs, unable ‘to bear the dazzling luxury that had been imposed upon it’ (80).

The manifestly sterile environment also extends to personal impotence, and we learn that before absconding from Paris, des Esseintes threw a dinner party mourning his ‘dead virility’ (45). While alone he dwells on past failed affairs with circus performers who promised to reignite his desire through their non-normative talents. These included a ventriloquist who makes statues argue for his sexual gratification, and throws her voice to simulate attackers trying to enter the room while they are in bed together. In another passage, des Esseintes argues that the beauty of women is matched by those of steam engines, professing admiration for a ‘monumental brunette with a deep husky cry, her brauny loins constrained by a cast-iron girdle’ (55). Again, des Esseintes’ craving for mediated sexual stimulation preempts a hallmark of the pandemic: the technological monopoly that internet porn blockbusters, vibrators and sex dolls have on the erotic lives socially-distanced singles. His behaviour parodies the mixed feelings of fear, liberation and misrecognition that come with forays into nonhuman pleasure.

The refinement of des Esseintes’ desires has the eventual outcome of upending the fundaments of another kind of appetite, for food. His irritable stomach and bowels seem to distil the indigestibility of his new, anti-natural reality, causing him to progress from a chosen diet of bland meals to feeding himself with a musical ‘mouth organ’ that emits a symphony of variously flavoured liqueurs. Towards the end of the book his digestion takes a further turn, and a doctor prescribes a diet consisting of a disturbing concoction taken as an enema: ‘Cod liver oil 20g, Beef tea 200g, Burgundy 200g, yolk of one egg’ (226). It is unclear whether there is a touch of sickbed satisfaction in his observation that ‘food consumed in this way was, without a doubt, the ultimate deviation that one could commit’ (225), but as a scatological crescendo in the questionable narrative arc, we might see the extension of des Esseintes’ ‘taste’ to include food favoured by his rectum as interrogating the very basis of consumption itself.[1]

Reading this book in lockdown put a disturbing spin on the luxury isolation arrangements, and further exaltation of private property generally, that have become hallmarks of the ‘new normal’. À rebours highlights the perverse luxury of being able to isolate with an income and have your every need delivered to your door. Des Esseintes is an illustration of how privilege works despite the metaphysical strain of being cooped up, his ultimate inability to digest his fully private reality coming into conflict with the pains he takes to preserve it. In attempting to escape a society that he condemns, one in which he occupies a peak position, he turns the nineteenth-century logic of imperial moralism, ordinarily directed at the racialised and sexualised ‘masses’, back on itself. In doing so, he beheads his own personal world but finds no greater good to exalt in its place. No greater good but things, glutting himself in unnatural consumption of books, artworks, and other manufactured stimuli down to food. Preempting the ascendance of digital media and other technologies, the representation of risk and novelty are the only ‘pathogens’ that makes it into des Esseintes’ highly regulated bubble. The situation seems to lead to a self-recognition as a parasite: ecocidal refinement backfires to necessitate the destruction of his own body precisely through the stimuli he had previously sought solace in.

In demonstrating the unsustainability of avid and isolated consumption of outsourced stimuli, the book also relates to a concept of decline many named in the events of 2020, a climaxing metaphysical fallout in which escalating structural tensions have been obviated in the lives of even the most privileged. The phrase for ‘countdown’ in French is ‘compte à rebours’, relevant when considering the grinding- and winding-down of des Esseintes’ lifestyle to a point of crisis. It is this factor that underlines À rebours historical consideration as a representative specimen of ‘decadent’ literature, what adherent Arthur Symons described in 1893 as ‘a new and beautiful and interesting disease’, spreading across artforms in multiple countries. The term comes from ‘the decadence,’ a historical period of decline leading up to the dissolution of the Roman Empire. Literary artefacts from this era are written in a ‘corrupted’ and polyphonic version of Latin des Esseintes delights in reading throughout his confinement. The experiential excess represented by these twilight years of Rome—think Cleopatra dissolving a pearl and drinking it, though she is of an earlier period—is as fitting with des Esseintes’ compulsive exhaustion of the resources and experiences available to him as it is with the perennial decadent characteristic of consumption today.

A year before the virus took hold, John Galliano would identify the same historical parallel, taking it as inspiration for his SS19 ‘Artisanal’ Co-ed collection for Maison Margiela. In his explanatory podcast he connects the malaise of decadence at the end of nineteenth century with the disillusionment he sees in Gen Z. The runway show begins with a very ‘viral’ assemblage of form-obscuring, icon-heavy, overloaded neons, becoming more and more pared back as the garments progress. The final look is an all-black leather romper, a cross between a straightjacket and a body bag, which obstructs the arms, for touching and acting, but not the mouth.

As I returned to À rebours in lockdown I found myself bothered by a raw-red throat and spells of breathless lethargy, eventually joined by worsening digestive function. Leftovers from my own brush with the virus six months prior—or perhaps just results of an extreme lifestyle change, it’s hard to tell. Turns out that many long COVID survivors experience gastrointestinal disorders, an effect that can only contribute to the rise in such disorders that has been seen in recent years. Anecdotally almost everyone I spoke to while writing this admitted having digestive issues either currently or in the past. The psychological inflections of this are unclear, but surely the metaphysics cannot be ignored: food is concomitant with our experiences, with content, and the manufactured material underpinnings of our lives. How we live, in or out of doors, with or without the virus, is enough to make one puke.

Naarm, December 2020

[1] In fact Raymond A. Prior has argued the chapter structure is a replication of peristalsis in his article ‘Consumption to the Last Drop: Huysmans’ Dyspeptic Tale of Eating, À rebours,’ in Disorderly Eaters: Texts in Self-Empowerment, Eds. Lilian R. Furst and Peter W. Graham, University Park: Penn. State University Press, 1992: 185-198.

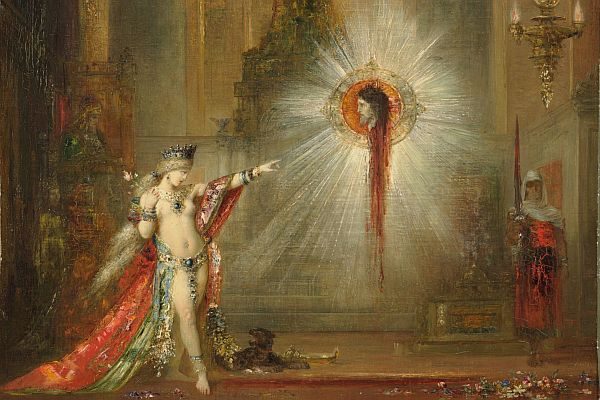

Image: Gustave Moreau, L’apparition, 1876 (detail)