At least since Herodotus showed up in the fourth century BC, Greeks have been visiting the Kemet–the ancient name for Egypt, meaning ‘the black land’. Many decolonial scholars have argued that what we know as Greek Philosophy is in fact partly a re-interpretation of North African Egyptian thought.

Many historians have pointed their lenses at the life and the work of several African thinkers and activists, including those at the forefront of the decolonial wars for independence in the continent. Although names like Aime Cesaire and Frantz Fanon are often mentioned, Lusophone African intellectuals and activists have received limited attention, particularly in the Anglophone world.

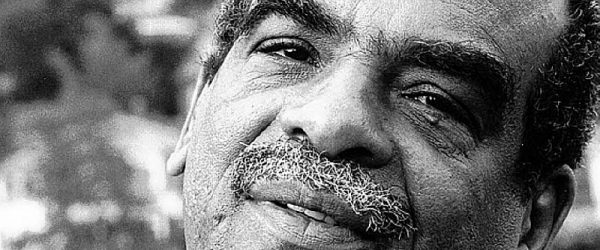

Perhaps no name is more important and influential in the African-Portuguese scope than Amilcar Cabral.

Amilcar was born to Cape Verdean parents in 1924 in the Bafatá region in central Guinea-Bissau. In the year of 1956, he was a founding leader of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC). Later on, he and the party would be crucial in defeating the colonial Portuguese Army forces.

Cabral’s political trajectory is intrinsically connected to the process of construction and the liberation struggle in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. He played a crucial part in the political and pedagogical thinking of that movement, from the beginning of the struggle in the 1950s to his assassination in Guinea-Conakry on January 20, 1973.

Two years after completing university studies at the Instituto Superior de Agronomia in Lisbon, Cabral turned down an assistant professorship at the same institute. Instead, he moved back to his country under a contract for the Ministry of Overseas, where he took a position as the main person in charge as a deputy for agricultural and forestry services.

His job would be to carry out the first agricultural census in Guinea-Bissau. This experience of direct contact with the country-dwellers allowed him to get to know in-depth the social, economic, and political reality in the entire Guinean territory.

Once the clash for independence was in full swing, Amilcar travelled the world seeking support for the fight against Portuguese colonialism in Africa. In a speech in front of the United Nations Assembly, he said:

This is not the place for a recital of the crimes of Portuguese colonialism, of which world opinion is now well aware. It will suffice to recall that from the time of the slave hunts until the massacres of today, the people of Guinea have been the constant victims of these crimes.

Cabral published a number of texts that have become essential references for the fight against colonialism and racism for the African Diaspora in the United States, Brazil, and several other countries. His influence can still be felt amongst members of Black militancy to this day. Following his assassination, both The New York Times and The Washington Post stated that Amilcar Cabral was ‘considered the most brilliant and successful leader’ of the struggle for independence in Africa.

Cabral was a humanist, and for him, things were more than just black and white. He more than once made clear that his war was against the colonial forces, not the citizens of Portugal:

We never confuse Portuguese colonialism with People of Portugal, and we have done everything, as far as we can, to preserve, despite the crimes committed by the Portuguese colonialists, the possibilities of cooperation, friendship, solidarity and collaboration effective with the people based on independence, equal rights and reciprocity of advantages, whether for the progress of land or for the progress of the Portuguese people.

The great Brazilian pedagogist and philosopher Paulo Freire acknowledged the influence that Cabral had on his work. In an interview, he stated:

In Cabral, I learned a lot of things, I say in Cabral also meaning with Cabral, I learned a lot of things. I also confirmed other things that I suspected.

Although Freire never met Cabral, whom he called the ‘revolutionary educator’, he visited Guinea-Bissau and spent much time dedicated to understanding Cabral’s ‘revolutionary’ educational concepts ideals.

When asked about Cabral’s utopian views, he replied:

The revolution that doesn’t dream is doomed. So is doomed the revolutionaries who don’t dream. The question that arises from the dream is just to know how they [revolutionaries] will fight to make the dream viable.

When describing his unique perspectives, Freire calls Cabral a Prophet because ‘a prophet or prophetess is exactly who, by living today intensely, can guess about what is coming tomorrow.’

Paulo Freire saw education as a practice of freedom and, as a result, of decolonisation and independence, as is attested by his first two books (Education as a Practice of Freedom and Pedagogy of the Oppressed), and, in a broad sense, by his life trajectory. Freire’s presence in Guinea-Bissau in 1974 was decisive in forming this view since it gave him the possibility of confronting himself more closely with the contradictions of the process.

I am no iconoclast: Freire’s contributions to human thinking are undeniable and irrefutable. However, Amilcar’s influence on Freire and his work is profound. As an unsettled human who continually questioned our purposes as species, Freire would appreciate his work to be debated and pushed further.

Freire’s work was built on many influences, just like academic thinking is empirical, and there is nothing wrong with this fact. However, Freire’s thinking originates in philosophies and ideas central to the African experience. Those ideals are rooted in African thinking from the dawn of humanity. As an Afro-Brazilian, I must pay my respects to Paulo Freire’s contribution to humanity. It is also my responsibility to remind everyone that, because of Amilcar Cabral, Freire was carrying a little bit of African thinking with him in his books.

A shorter version of this piece was delivered at the ‘Education and Social Justice Across Borders: Celebrating 100 Years of Paulo Freire’ academic conference held in December 2021 at the University of South Australia, organised by Associate professor Joel Windle.