It was in Glasgow during the twilight of the eighteenth century that mechanical engineer James Watt developed the early steam engine that would help catalyse the Industrial Revolution. It’s to this epochal moment in human history that English philosopher and environmentalist Timothy Morton traces the intersecting ecological crises we face as citizens of the twenty-first century. In Hyperobjects (2013), Morton wrote that:

The end of the world has already occurred. We can be uncannily precise about the date on which the world ended … It was April 1784, when James Watt patented the steam engine, an act that commenced the depositing of carbon in Earth’s crust—namely, the inception of humanity as a geophysical force on a planetary scale.

It’s interesting, then, that in a few days’ time Glasgow will play host to what has been widely proclaimed as another moment of world-historical import—one we’ve been led to believe has the potential to slam the brakes on the carbonisation of the planet that Watt’s invention set in motion.

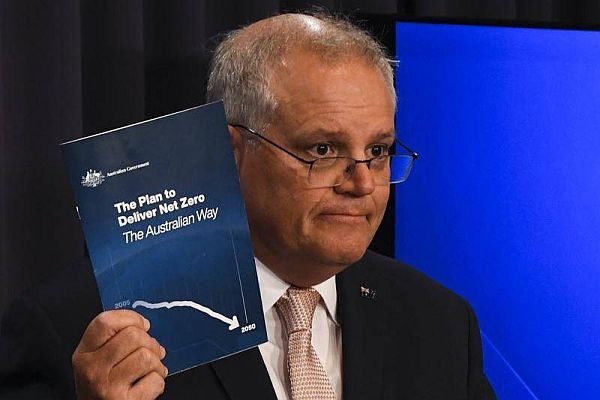

In the lead-up to COP26 there has been a palpable shift in the global politics of climate change. Almost all developed countries will go to Glasgow with a target of net-zero emissions by 2050 in the bag, with many, including the UK, the US, and China, also taking significantly strengthened 2030 targets. Under pressure to do likewise, and following the striking of a typically opaque deal with its Coalition partner, the Nationals, the Morrison Government this week belatedly announced it, too, was on board. On Tuesday, we got our first look at the plan, presented by the Prime Minister in the form of a glossy brochure unpromisingly titled ‘The Australian Way’.

Its contents can be easily summarised, even if they read like an absurdist play. According to the plan, Australia will reach net-zero by 2050 by … doing nothing. The document outlines no new polices or mandates to reduce emissions. It cites no economic modelling—which might exist but, according to Minister for Finance Simon Birmingham, is ‘cabinet in confidence’—and relies on technologies that have yet to be proven to work, or even not to work for that matter.

The plan is a ghost document, sutured from the blood-drained remnants of actual policy and haunted by the unmistakable stench of a once and future PR man shitting himself not over the unfolding climate catastrophe but the threat of carbon tariffs and his political standing at home and abroad. ‘Morrison,’ CNN pithily observed, ‘will go to COP26, reluctantly, with the weakest climate plan among the G20’s developed nations.’ That ‘The Australian Way’—the Waiting for Godot of international climate policy—has been hailed by some journalists as the end of Australia’s climate wars shows how utterly inane the discourse has become.

In reality, the plan maintains the same old framing that has, at least since Tony Abbott’s brutal retail politicking around a carbon ‘tax’, reduced the climate crisis to a political rather than environmental or moral problem. The space once occupied by parliamentarians—recall Kevin Rudd’s ‘great moral challenge’ speech—is now the domain of school students and Indigenous activists taking the Government to court. The Labor Party, which has no 2030 emissions target either, is scarcely less culpable. Perhaps it’s little wonder that politicians as singularly lacking in vision as Morrison and Albanese—not to mention as beholden to the fossil fuel industry, and an election cycle as dangerously short-sighted as ours—should find it so difficult to conceive of the climate crisis in Morton’s terms: as the apocalyptic consequence of a human collective now sufficiently powerful to destabilise the Earth’s biosphere and threaten futurity itself. But then accepting the existential nature of the problem would not only expose the limits of a conference of nations—it would also reposition the comparatively radical demands of the climate movement as the only sane response.

Critics of the Government’s chimerical plan are already being denounced for ‘moving the goalposts’. On radio this week, speaking about recent Extinction Rebellion protests in Adelaide, I was accused by one host of being ‘professionally unhappy’ in dismissing the idea of 2050 targets. Nothing our political leaders do, this line of (non-)thinking goes, will ever be good enough. But anybody who’s been paying attention knows that 2050 was always a convenient fiction. It is simply too little, too late. Extinction Rebellion has long agitated for 2025 targets. The Climate Council argues for 2035, and emphasises the need for an interim emissions reduction of 75 per cent below 2005 levels by the end of this decade.

Let’s be clear: as Ketan Joshi noted on Twitter, the 35 per cent reduction by 2030 included in the plan and uncritically reported in much of the media is nonsense, and fudges important information about Australia’s energy mix. Because of course it does: this is a Government that continues to tout the role of fossil fuels in our energy production for decades to come, and that gifts billions of dollars of public money to coal, oil, and gas companies while trash-talking renewables at every opportunity.

If all of this is representative of ‘the Australian way’, it isn’t this country’s supposed robust pragmatism but its lazy complacency (‘she’ll be right’) that’s truly being invoked. The Government may wish that meaningful emissions reductions—as though they alone are any kind of panacea, given how much damage has already been done and cannot now be prevented—can be magicked out of thin air without disturbing their cosy alliance with fossil fuel companies. But they shouldn’t expect us to believe in another Morrison ‘miracle’.

These are, after all, the same people who have spent the past eight years not only dragging their heels on climate action but denying the physical reality of the planet itself. To use a phrase beloved by the Prime Minister, Australia—a country blessed with abundant renewable energy sources—should by now have the gold standard of global climate change policy. Instead, we’ve emerged at the end of almost a decade of literal and figurative coal-fondling with a ‘plan’ that isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.

I once cared, when it was anything but certain, whether Morrison went to Glasgow or not. But I now see that such thinking is part of the problem, trapping us within the same, narrowing frame set by the Government and the parts of the media that fail to properly hold it to account. The cost of Morrison’s failure to take a consequential plan to COP26 should not be measured in terms of political capital, but in the temporally unlimited threat its absence poses to both human and non-human life. At this point in history, almost two and a half centuries since Watt’s steam engine inaugurated the era of anthropogenic climate change, those who continue to back the carbon industries are not incidentally enabling the growing catastrophe—they are insisting on the right to prolong it.

If we’re going to call on the Australian imaginary, then let’s look to another national tradition in our response to ‘The Australian Way’: refusing to be taken for mugs.