CW: mental illness, suicide

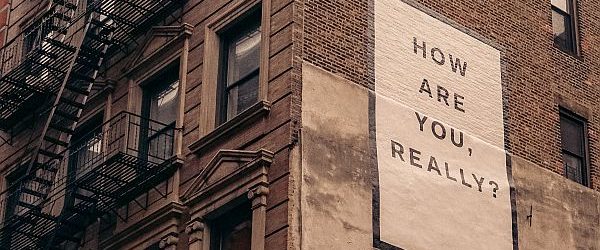

Encouraging frank conversations about ‘life’s ups and downs’, R U OK? Day has become one of the most recognisable mental health campaigns on our national calendar.

Each year in September, Australians are invited to check in with family members, friends and workmates to ask how they’re really going. By ‘empowering people to meaningfully connect and lend support’, the organisers explain, we can strengthen the kinds of relationships that reduce stigma around mental illness and actively protect one another from self-harm and suicide.

Unlike traditional self-help approaches to managing mental illness, R U OK? Day is grounded in a social model of support and recovery that emphasises early intervention through authentic connection. The resources are practical and friendly, suggesting a four-step approach to initiating potentially life-saving conversations—including prompts to seek specialised help from a mental health professional where needed.

Even in its sensible bid to ask, listen and encourage action, however, R U OK? Day obscures a more complex and uncomfortable reality: that appropriate professional support is not always readily available, and that many individuals most at risk of depression, self-harm and suicide are those whose repeated efforts to take action have already been frustrated by demoralising interactions with the healthcare system.

In Australia, as in many countries around the world, awareness, availability and affordability represent some of the most obvious barriers to accessing appropriate mental health support when it’s most needed. Even if they’re aware of what’s available, people seeking treatment for debilitating mental health concerns—such as major depression, anxiety disorders or substance abuse—often serve long waiting periods and pay significant out-of-pocket expenses.

In a study published earlier this year, researchers from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute reported that parents face extensive wait times and substantial financial outlays when seeking private mental health services for their child. On average, close to a third of private practices were closed to new referrals. The average wait time for psychiatrists and psychologists was forty-one and thirty-four days respectively, and average out-of-pocket costs quoted were $176 for psychiatrists and $85 for psychologists.

For more than a decade, the Australian Government has subsidised appointments with mental health professionals for Medicare cardholders, currently offering up to twenty sessions through a GP-enacted mental health treatment plan. While this contribution no doubt makes counselling more affordable to some help-seekers, the gap payments remain too steep for many others: the standard rebate per session on a mental health treatment plan is just $77.80 while the Australian Psychological Association’s 2021–2022 recommended schedule of fees has set the standard 46–60 minute consultation fee at $267.

Even patients who present to emergency departments with acute mental and behavioural conditions face longer waiting times than others and are more likely to leave the ED prior to their treatment being completed—at their own risk and against medical advice. And, as South Australian writer Kylie Maslen has observed in her recent memoir, Show Me Where It Hurts, adults who experience an array of chronic illnesses, especially women and members of marginalised groups, may suffer a double financial whammy in their reduced capacity to work coupled with sometimes crippling medical expenses. (It is worth noting that half of all Australians living with a chronic health condition experience depression or anxiety.) Put more simply: those who need mental healthcare the most are often unable to afford it.

Other factors—including the considerable time and effort involved in seeking and coordinating care, rushed or otherwise discouraging appointments with health professionals, negative or unsatisfying responses to medications and other treatments, and intersecting layers of social disadvantage, such as minority status or language barriers—pose additional challenges that can undermine the perceived payoff of help-seeking behaviours over time.

*

When I presented to a private emergency department in early 2013, my parents and I reasoned that paying out of pocket would be worth it for a same-day admission and urgent psychiatric review.

‘Please don’t make me go home,’ I had sobbed on the street outside my mother’s office, feeling desolate after an appointment with my regular GP in which she’d gripped me by the wrists and told me sternly that I needed to be strong and simply ‘get past whatever this is’.

Having nursed me through more than a decade of increasingly severe depressive episodes, my family was exhausted. I was twenty-nine years old, living at home again while unable to work more than a few hours a week, so overwhelmed by the unrelenting darkness inhabiting my brain and bones that I’d sometimes still crawl into my mother’s bed at night, afraid to be alone.

The opposite of depression is not happiness, American author Andrew Solomon has pointed out. It is vitality. And at my worst, I was more afraid to live than to die.

One psychologist I saw for several months blinked disbelievingly when I described sensations of terror upon waking, a cellular dis-ease that transcended or evaded any form of logic or expression—a kind of existential nausea. My whole body was malfunctioning, I tried to explain, my mind always playing catch-up, unable to make any sense of it.

‘No. Thoughts always precede feelings,’ she insisted, tapping the cover of a CBT manual. ‘Let’s work on disputing some of those thoughts.’

I stopped attending.

Prescription medications seemed to cause more symptoms than they quelled. While taking a commonly prescribed tricyclic to help mitigate my persistent insomnia, I gained so much weight in a matter of weeks that none of my clothes fit any longer. Tapering from one SNRI to try another, under advice from a doctor, pushed me into a suicidal spiral.

‘This isn’t you. It’s withdrawal syndrome,’ an after-hours GP assured me one night when I’d rattled through a kitchen drawer searching for a knife sharp enough to open a vein. He sent me home with a rueful smile and a more conservative regimen to follow, pencilled onto the reverse side of a prescription sheet.

There were so many tablets, the brand names all a mouthful of meaningless syllables. Zoloft. Cipramil. Neulactil. Avanza. Endep. Seroquel. Cymbalta. When I failed to demonstrate a positive response from one fortnight to the next, the psychiatrist would prescribe a higher dose, add in something new.

In between the counselling sessions and pharmacy refills, I tried other ways to combat distressing symptoms and sensations. I saw natural health practitioners, took nutritional supplements, walked laps at the indoor pool, lay in the sunshine, avoided gluten, asked a family friend to administer vitamin B12 injections.

‘People are praying for you,’ my mother would remind me. A family friend lent me a Coles green bag full of self-help books. I toyed with the covers, never able to concentrate for long enough to decipher more than a page or two inside.

I tried and tried, until finally: that unbearably bright end-of-summer afternoon, my parents shielding their eyes from the sun as I begged through tears, ‘Please don’t make me go home.’

Four months as a psychiatric in-patient, including sixteen applications of electro-convulsive therapy, probably saved my life. But in other ways, those days spent huddled in a hospital room left me so broken—not to mention broke—that I’m haunted by the experience even now. My previously supple memory never quite bounced back from ECT. My treating doctor eventually pronounced me ‘incurable’. And it took me years on a PhD stipend supplemented by casual university teaching to repay my medical debt.

As a student struggling with the pressures of doctoral study and advanced autoimmune disease, I experienced a familiar sense of anxiety about the potential cost of regular appointments and developing rapport with a new therapist. Only last year, I terminated my sessions with a psychologist available through my workplace’s employee assistance scheme when they pressured me repeatedly to try the (largely debunked) liver-cleansing diet and spent more time describing their success with other patients than taking my own medical history.

Help-seeking is a well-trodden path in my adult life, one that requires persistent courage and energy that is not always rewarded.

*

My experiences are not unique.

Over the years, friends and family members who have pursued support for their mental health have also described tortuous paths that left them tired, traumatised and sometimes unwilling to seek help again: insensitively administered assessment instruments, accusations of histrionics and doctor-shopping for prescriptions, difficulties juggling therapy around other responsibilities, and even gross violations of privacy. When I interviewed individuals with a history of depression as part of my research, many participants explained why they’d turned to reading as a cost-effective and less invasive way of accessing psychological help when mainstream medical practitioners and approaches had let them down or proved unsustainable.

Although some impediments to ongoing help-seeking behaviours such as cost and distance are well documented in the literature, more detailed descriptions of experiences like these are less likely to be captured in scholarly research due to the tendency for study designs to favour carefully structured programs administered under artificial conditions—and to collect and report quantitative data. In other words, what consumers experience in the real world may differ significantly from within a randomised control trial, and the results are often decontextualised from richer descriptions of lived experience. However, contemporary research does indicate that even persistent attempts to seek help may not result in met needs—and may even result in additional trauma—due to a range of factors including mistrust in the medical system more generally, stigma from primary healthcare providers, and poor ‘fit’ with therapists and recommended techniques.

Online forums and discussion boards offer a useful source of insight into people’s experiences of seeking and undergoing treatment for mental health concerns—as well as clues about why they may resist or stop. When Dr Carli Ellinghaus and colleagues took a qualitative approach to understanding the experiences of young people exposed to childhood trauma by collating narratives from online forums, their findings identified both structural and relational barriers to help-seeking attempts. Structural barriers included navigating logistically complex systems and receiving insufficient treatment. Relational barriers included disruptions to the therapeutic relationship and invalidating responses from professionals. ‘I’m tired of being pulled from pillar to post,’ a poster remarked in one example.

Browsing online forums, I’ve read dozens of similar accounts from individuals trying to engage actively with mental health services. Even one-off encounters with health professionals can have a lasting negative impact on individuals at risk of self-harm and suicide. One Reddit user, for example, in a thread about psychotherapy, described a distressing encounter with a psychiatrist, concluding: ‘After that session, never went back, never returned a call or initiated a call, nor have I attempted counselling again.’ A guest posting on a popular Australian mental health forum reported that they were ‘scared out of their mind’ to be starting with a new psychologist that week. ‘If it doesn’t work out this time,’ they commented, ‘I don’t know what I can do to help myself anymore.’

*

The reality for many Australians is that taking action in the event of someone not being OK may result in outcomes that accentuate, rather than alleviate, suffering and a reluctance to seek help. And as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold, pressure on the healthcare system is only intensifying.

This year, the Australian Government committed to investing a record $2.3 billion in mental health and suicide prevention over the next four years. Big-ticket items include $487 million to establish a national network of adult mental health centres and $111.2 million in digital services—a welcome boost that will have genuine life-changing potential for thousands of Australians.

However, experts caution that even this seemingly generous contribution will not be enough to accommodate increasing demand, and that expanding services in and of itself does not necessarily result in improved outcomes. Despite considerable increases in mental health services over the last twenty years, particularly through the federal Better Access initiative, researchers have observed little detectable impact on crucial indicators such as the national suicide rate. Increasing services may even lead to progressively more people receiving support that is ‘too thinly spread or poorly targeted’ to make a real difference. We need to be thinking about quality as well as quantity, says Emeritus Professor Anthony Jorm, who advocates for more nuanced approaches to supporting individuals with mental illness and a greater emphasis on prevention and early intervention.

R U OK? Day is one such initiative that offers a refreshing counterpoint to individualistic, too-little-too-late models of mental health support. But it also serves as a reminder that we need to keep asking the harder questions.

If a significant number of Australians have contact with health services in the weeks before dying by suicide, for instance, what opportunities for intervention are being missed? If general practitioners are typically the first points of entry to professional mental health services, how do we ensure they have the capacity and confidence to support patients in a sensitive, meaningful way? How can we more carefully triage patients who present to emergency departments so they are assessed and treated in a timely, effective manner? How might we cater more authentically to disadvantaged Australians whose attempts to seek help are often compromised by cost and complexity? What steps can we take to better coordinate services and reduce the logistical burden of engaging in comprehensive mental healthcare plans? How do we ensure that attempts to seek help do not ultimately result in harm or additional trauma? And how might we embed or normalise a more flexible approach to mental health support in which both practitioners and patients understand that improvement usually takes time and experimentation?

As someone who has grappled with self-harm and suicidal ideation, I can personally attest to the healing power of meaningful interactions: co-workers who check in, doctors who listen, friends who send flowers or volunteer to drive you to an appointment. Encouraging one another to seek help is vital to our long-term health and wellbeing. However, we must also strive to ensure these critical conversations honour the efforts that at-risk individuals are already making and that we hold the healthcare system to account so that high-quality support is actually available to those who need it the most.