There is certain horror that follows the retraction of a paper from one of the most prestigious biomedical research journals. These papers normally move mountains in the medical world – treatment regimens are changed, policies are made, promises are made to new cohorts of patients who are able to gain access to potentially life-saving therapies (whether this access is made affordable is a whole different discussion). On an ordinary day, a retraction due to misconduct is bad enough. During a pandemic that has seen so much death and suffering, it is unconscionable.

An investigation by The Guardian has uncovered deep flaws in a database used to publish research on COVID-19. Hospitals had purchased this data from a private company, interrogated links between the drug hydroxychloroquine and the health outcomes of COVID-19 patients, and then published in some of the most influential medical journals in the world of research. Conclusions drawn from the data suggested that hydroxychloroquine was associated with a higher risk of death and heart complications in COVID-19 patients. But there were clear inconsistencies in the database and little transparency as to how it was created. The papers were eventually retracted. More recently, a study supporting ivermectin as COVID-19 treatment was withdrawn due to a number of errors, and signs of data manipulation and poorly-disguised plagiarism. While not yet peer-reviewed, the research was already being cited as evidence to support the use of the drug in the fight against the pandemic.

The peer view system was created to prevent this from happening. But time and time again, it has demonstrated that it is fundamentally broken. Reviewers – themselves scientists with a full load of research, supervising staff and students, writing grant applications, and volunteering for committees to bolster their CVs – are normally allotted two weeks to assess the credibility of research. This time-pressure impairs their ability to spot even the most obviously doctored image, let alone give them the opportunity to analyse any raw data (if any are provided).

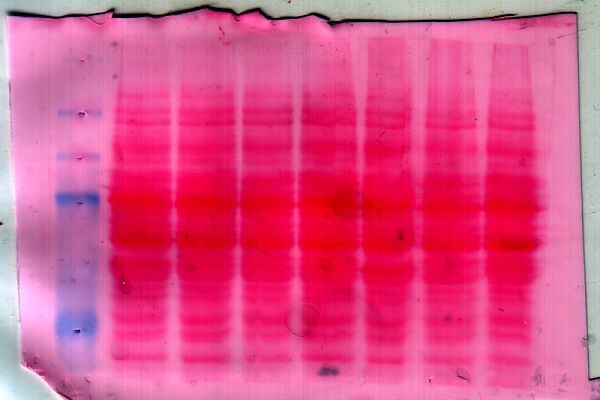

This systemic failure has caused a shift, whereby identifying potential research misconduct has transformed into crowdsourced mission. Retraction Watch is a collective of online sleuths dedicated to spotting irregular patterns in a number of research fields, while PubPeer – a forum established to encourage rigorous debate about scientific findings – has found itself morphing into an online whistleblowing platform. Here, scientists dissect ‘red flag’ papers, taking deep dives into numbers in tables, interrogating error bars and zooming in on figures. Has this western blot band been copied and pasted? Does this quadrant of this scatter plot look familiar? Should this photo from a microscope look like a tessellating pattern? With no place to turn, scientists have become data vigilantes.

What is most disturbing about these investigations is the pattern of repeat offenders. There is no set of universal consequences for scientists who are caught. Some simply move on, and continue receiving awards, grants, recognition and prestige, their misconduct suppressed and silence enforced. Sometimes, there are tragic outcomes, as in the case of the death by suicide of Japanese scientist Yoshiki Sasai following the retraction of a ‘blockbuster’ paper. And every once in a while, there is a devastating legacy: or who can begin to measure the damage caused by Andrew Wakefield’s discredited research on the supposed link between the MMR vaccine and autism? In all cases, a question is begged: why do scientists falsify their data?

The ‘publish or perish’ adage is one that is burnt into the brain of every biomedical researcher, perfectly encapsulating the cyclical, Sisyphean task faced by scientists. The more (and mostly positive) data you gather, the more papers one can publish. And the more papers one can publish, the more funding one will receive. In Australia, with funding for biomedical research, through the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the Australian Research Council (ARC), falling in real terms over the years, competition for a limited pool of cash has become increasingly cutthroat.

With pressure mounting, timelines contracting and the question of whether there is enough money in the lab budget to pay for research expenses or wages for another year, inevitably, there is slippage. From garden-variety photoshopping of images to copying and pasting numbers, there are a multitude of ways to manipulate data in service of providing evidence in support of a hypothesis. It can be digital or it can be manual. It can be carried out under the cover of darkness or in plain sight. It can involve one or many, anywhere in the chain of command of a lab.

In Australia, the government’s failure to fund Australian biomedical research and universities will see a catastrophic decline in discovery and treatment development. Junior researchers are finding it more difficult to support their work, while women continue to leave the profession in an exodus known as ‘the leaky pipeline.’ The funding ecosystem has created disparities at leadership levels in biomedicine and it is an issue the sector is only beginning to attempt to address. We’ve become bystanders, witnessing the arbitrary application of market scarcity and of competition to the mindset of publicly-funded science.

Why don’t more scientists speak out? As with most, if not all, academic fields, biomedical research is entrenched in hierarchical structures. The dichotomy between the spirit of an endeavour that is rooted in innovation and evolution, compassion and humanity, and the systems that hold up science which are deeply political, prone to bias and resistant to change, is enough to give anybody whiplash. It is these hierarchical structures, and the power dynamics embedded within, that create an uneven playing field and breed a culture of silence. What chance does an undergraduate student have against a Goliath in the field?

This crisis is accelerating the erosion of public trust in research. From anti-vaxxers to COVID-19 deniers, the tide is turning against scientific institutions. While criticisms of Big Pharma and capitalism in biomedicine are valid and necessary, and are issues we need to reckon with as a global society, it has become harder and harder to separate them form conspiracy theories.

It was one of the most infamous cases of scientific misconduct, muddled by a financial motive, that has fueled the modern and insidious anti-vaxxer movement. Published in The Lancet, one of the world’s leading medical journals, Andrew Wakefield’s ‘autism’ paper was retracted after findings of unethical conduct and falsification of the data. It was also discovered that Wakefield had a financial stake in his findings, as he had ties with a law firm suing vaccine manufacturers, and had submitted patents and formed startups designed to capitalise on the fears his paper would likely cause. While Wakefield was eventually struck off the medical register and his claims have been rebuked by extensive research, the damage had already been done.

Discovery and altruism are deeply human pursuits and humans are fallible. Biomedicine and science are not exempt from this. There are many good scientists doing good science. But it is time to cast our eyes on the systems and the failures within the systems that have allowed this problem to fester. It is time to reimagine a structure for science that not only speaks to but also practices transparency and accountability.

Image: Wikimedia Commons