One Sunday night a few weeks ago, I received an email from Podbean – the service that hosts my podcast Better off Read – informing me my podcast had been taken down in response to a complaint that the content on the first ever episode, back in 2014, infringed on ‘intellectual property rights worldwide’. It wasn’t until about twenty-four hours later that I was able to clarify the nature of the alleged breach. The emails I received up until then, were heavy on the terrifying legal-language but light on details.

The complaint had come from AXG House, an ‘automated DCMA [Digital Millennium Copyright Act] take-down service’. Starting at about 120 Euro a month AXG House will monitor the internet for your content, request removal and track the removal process. AXG House uses keyword scans, automated crawling and ‘deep manual searches performed by our experts’. When their systems find customers’ work being shared, AXG House issue a takedown notice to the site, which is then legally obliged to remove the file and/or page.

One of the services AXG House offers is a ‘Publishing Anti-Piracy Service’ aimed at detecting and removing unauthorised sharing of e-books, audiobooks, magazines, newspapers and e-learning resources. Apparently, this was the one my podcast triggered: their email requested I immediately cease to provide access to Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 (although, when I checked the ISBN they supplied, it referred to the Italian language e-book). The offending episode was a discussion with writer Aidan Rasmussen using 2666 as a way to talk about Aidan’s own writing practice.

AXG House estimate that 1 in 500,000 take-down orders are sent incorrectly to legal and fair use content. It is for this 1 in 500,000 that AXG House ‘practice human verification’. Clearly, no such verification had occurred in my case. Podbean’s process to take down my account was also likely automatic. Their emails indicated that if I ‘violated copyright a third time,’ my account would be ‘permanently closed’, and that I was only allowed to contact them after removing the content the complaint was based on.

I felt like Sandra Bullock in The Net, a film that looks clunky now but chilled me to the bone when I first saw it. One of its taglines was: ‘She has the evidence but they have the power’. I scanned the list 52-page of copyrighted material that came with the complaint, which included Moby Dick, Lolita and some of the works of Shakespeare, and pre-emptively deleted more episodes – I was afraid that what had happened automatically once could happen automatically twice more, at any time.

It seemed the only way to stop this was to stop talking about books, or music, or anything else that could be copyrighted. It wasn’t until I tweeted about all this and a friend with some clout sent an email to ‘the right person’ at Podbean that I received a brief email from AXG House, copying in Podbean, saying there had been a mistake and my provider should take ‘no further’ action.

I began my podcast in 2014 because I was interested in the relationship between reading and writing. After finishing 2666 I had this thought, that I couldn’t shake: ‘Are all books about writing?’ I kept thinking how Bolaño’s serial killer seemed very much like a writer to me. I started looking around and finding thoughts expressed in the world of a book that could also apply to writing. I thought that speaking to writers about reading, about the books they loved, would offer me an insight into their writing practice.

What attracted me to this idea was this ecosystem I imagined of existing books feeding the creation of more books. I’ve never been convinced by the concept of the ‘original, isolated’ work of genius. While I do believe that everyone has something to say that is distinct and compelling, what makes it compelling is the way these words have been formed by the culture they’re in. In some cases, we’re reading the same books, but there’s always an individual experience and a distinct combination of books, movies, music.

The way the copyright legislation is written encourages the type of automated take-down approach developed by AXG House. And because this automation is not built for purpose – the company itself admits to needing human ‘experts’ and ‘verifiers’ – it’s bound to catch people using content legally. Everything I read about DMCA highlighted that ‘by design and as interpreted [it] doesn’t do enough to protect online fair uses’. Users in theory can issue counterclaim notice (after swearing ‘under penalty of perjury’ and consenting to the jurisdiction of the US Federal District Court) but in reality, hardly anyone does.

This experience left me thinking that, perhaps, the flaw lay in the way the law has interpreted the ‘property’ part of intellectual property. This insisted on a distinctly Western, capitalist interpretation of something that can be bought and sold, and can only have one specific owner at a time. I would like to think instead of the concept of guardianship, of what Māori call kaitiakitanga, which conceptualises land as a living entity with connections and ties across time and space. How different would my experience have been if, instead of asking, ‘do you have something that belongs to us?’ AXG House had been asking: ‘Are you caring for the work of Roberto Bolaño? Are you expanding its connections and ties – ensuring that it carries on in good health?’

The Western, capitalist view of intellectual property supposes scarcity and this is what it writes laws to protect. Whereas a different view suggests that there is plenty to go around, that the work grows and multiples every time someone reads it or talks about it or makes art in response to it.

I love 2666. It remains one of the most influential books I’ve read. That’s why I wanted to talk about it with my friend, the writer Aidan Rasmussen. When I loaded that episode seven years ago, the thought other people could be part of this conversation, to share their love of the book or perhaps to discover it, was invigorating. As well as making my podcast, I write books and while I understand the market forces at play with the object of the book, I also find this generative model so much more in line with my experience. My books are a product of and largely love letters to everything I’ve read and watched and seen and heard. The fact they get to sit in the context of this work and that they might generate more work is what keeps me writing.

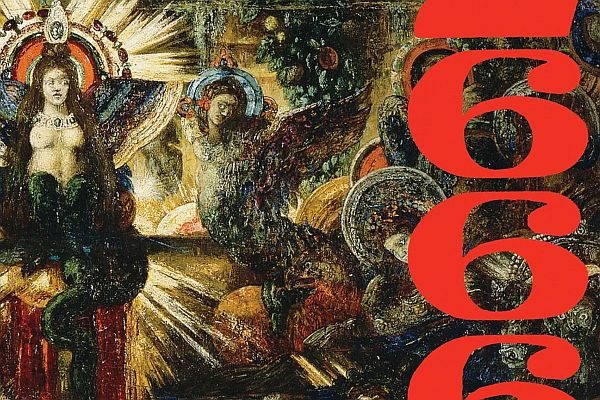

Image: a detail from the cover of the Picador edition of 2666