Immunity began as a legal and political concept, originally a part of Roman law. ‘Munis’ as civic duty, ‘im-’ as a negation. This could mean an exemption from taxes or from holding public office. The orator Aelius Aristides (117–181CE), for example, claimed immunity from costly public service by calling on high-ranking supporters.

The word was first used in a scientific or biological sense much later, in the nineteenth century. It was employed as a poetic device, rather than understood as a direct translation of the aims of cells.

Now, the language of immunity delineates the body as the unit of the individual. This conception of immunity – of the body’s ‘defence system’ – has become the defining understanding of health, and separates us, rather than connecting us.

We declare war on cancer and AIDS. We visualise white blood cells destroying tumours. We imagine we are fighting off a cold. We kill the germs that cause bad breath… The organism’s own cells now seem to engage in the very warlike actions that the modern state itself enlists to protects its subjects’ lives as its most vital asset. (Ed Cohen, A Body Worth Defending)

Using militaristic language to describe the processes of cells creates an ‘I’ that must be protected from external threats at all costs. This upends the porousness of the body itself, and of the relationship between self/community. The hermetically sealed ‘I’ need not care for others. The fear of what is external or ‘other’ allows our government to enact immoral and racist policies in the name of protecting the nation, using this same language of threat, of contamination.

Questions of health are always questions of community and mutual responsibility.

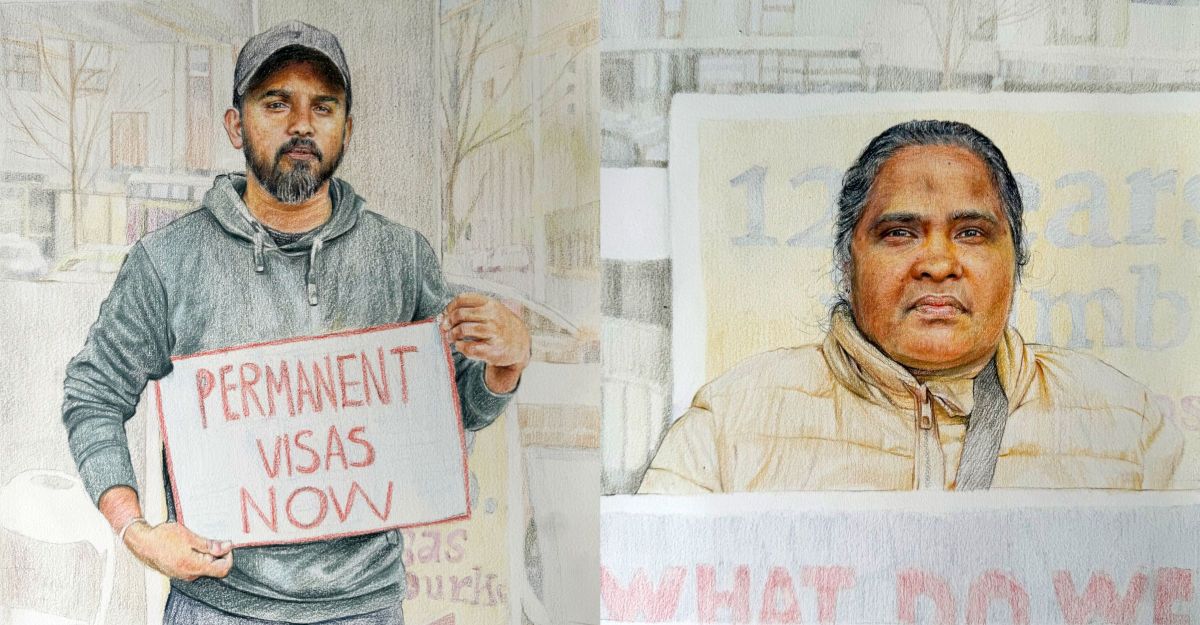

Borders and health: #FREETHEKP120 and #Mantra60

Like any law to be applied universally, immunity contains the contaminant of contradiction. The universal human right to seek asylum, unless. No arrivals by sea will ever see Australia, unless. The responsibility to provide medical care, unless. The Liberal Party’s website states that those who arrive without a visa by boat will not be settled in Australia, under the guise of ‘strong border protection’ providing ‘strong national security’.

This cruelty, of course, is bipartisan. It was Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd who declared in 2013 that asylum seekers arriving by boat would never be settled in Australia – an interesting stance for a colony founded by boat arrivals. The rationale of this policy is based in the perceived need for protection and exclusion, that is, immunity. That ‘we’ need to be protected from asylum seekers who are dangerous (either morally or supposedly having infectious diseases) at worst or an untenable burden on the country’s economy at best.

This is a fantasy, one exploited by private companies like Serco contracted to run Australian prisons and detention centres. If taxpayer’s money was the primary concern, another solution would have been found, because it is more expensive to detain people than to support them as members of the community. In reality, this system of indefinite detention is an exercise of power in the name of health, seeking to contain those marked as other in order to perpetuate systems of profit and power.

The short-lived Medevac Bill was passed in 2019 and allowed for the transfer of asylum seekers in offshore detention on Manus or Papua New Guinea to Australia for urgent medical care. To be medically evacuated, they would need to be assessed by two doctors as requiring treatment that they could not receive where they were detained.

In 2020, refugees who had been transported from offshore detention to Australia for medical treatment were detained in private hotels in Melbourne and Brisbane. A guard at the Kangaroo Point hotel tested positive for Covid-19, presenting a significant hazard to those housed there, as they were not able to socially distance and were at higher risk due to their health conditions. The refugees began hanging banners from their balconies at the same time every day, protesting their detention. Some had arrived as children and are now young men. Some have families in the community they cannot see or support. Their seven years of detention became eight during the period of protest.

This act of resistance in sight of the community had a remarkable effect. The responses ranged from peak-hour footpath sign-waving to larger-scale protests. An event co-ordinated by Refugee Solidarity Meanjin was attended by hundreds of people with clean hands and masks on disrupting the main road outside the hotel. The protests were met with police response disproportionate to the actions taken. Police used restrictions on crowd size and social distancing to combat protests. They read out Covid-19 directives and issued move-on orders. At other times, when the mood was more antagonistic, the police proved unable to keep their hands to themselves. A row of divvy vans with their doors open to receive protestors was parked in the middle of the street, acting as a warning.

More affecting than the police antagonism was the connection with refugees and their families. Members of the public engaged in a 24-hour blockade for a period of months to try to prevent the removal of the refugees from Kangaroo Point, where they could be seen, to Brisbane Immigration Transit Association – a higher security prison where they would be further isolated. They provided support to the refugees’ families in the community, and fundraised to cover the living expenses of those released. Refugee Solidarity Meanjin maintained clear demands for the protests: that those detained be allowed to walk outside, and ultimately that they should be released into the community by Christmas 2020.

These protests attracted disparaging media coverage, often under the guise of concern for public health. Protests for the #KP120 and #Mantra60 were not alone in this: Black Lives Matter protests were also falsely accused of spreading Covid-19.

Indefinite detainment is torture, and radically different to the stresses of quarantine endured by those outside. Those detained at Kangaroo Point and the Mantra hotel in Melbourne arrived needing medical treatment, and deteriorated. Those who spoke to the protesters – phone calls played over loudspeakers – spoke of anxiety, sleeping pills, suicide attempts, not seeing anyone except Serco guards. They spoke of wanting to see their families, to walk outside with all of us gathered. To join. There is no one in the hotel-prison now. They have been released into the community on temporary bridging visas, or removed to BITA. No reason has been given for why not all of them were released.

The idea that the government was safeguarding public health by imprisoning asylum seekers is riddled with inconsistencies. Our understanding of immunity is used to justify warlike approaches to medicine and the organisation of society, antithetical to healing or collectivity.

Immunity/community: self/non-self

A history of medicine is necessarily also a history of power, philosophy and technology. The approach to sickness (and health) of a society reveals its fundamental values. It is always caught up in the shared assumptions of how life is to be lived, and which lives are worthy of care. Their interplay is fascinating, and unlike a lot of philosophising, has a material, physical and often violent result. In A Body Worth Defending, Cohen posits that our society is organised in a ‘somatocracy’: rather than the monarch’s concern for, for example, our eternal soul, we have politicians concerned for our bodies, because ‘biopower appreciates life by recognising in it an exploitable natural resource rather than simply wielding death.’

History of Pain by Roselyne Rey details the development of medicine as a discipline, noting that the early use of both anaesthetics and inoculations was very much subject to a utilitarian value judgment:

[The] terms of the debates were complex not only in that they set the right to life of an individual against the advantages of the whole of society, but also in that they took into account the probability of catching an illness and of dying from it.

In the case of the use of anaesthetics,

all things being otherwise more or less equal, in other words with a statistically negligible increase in the risk of fatalities, the real choice was between suffering and not suffering.

In The Undying, Anne Boyer writes on her frustration with the pink and feminised discourse that surrounds cancer. She notes that cancer treatment is mired in the same language of battle that is used in ideas of health and sickness more widely. In the relational framework set out by sickness, sufferers and carers are both ‘marked by our historical particulars, constellated in a set of social and economic relations.’ She further notes that ‘the history of illness is not the history of medicine – it is the history of the world.’ She considers the environmental impact of the treatment drugs, of flushing her urine that, after treatment, is toxic to other living things.

Eula Biss wrote at length on her fears of contamination and toxicity after the birth of her child, which occurred around the time of SARS. She gave the example of Triclosan, a common antibacterial agent that has been found in human blood and tissue globally. Yet she still chose to use the antibacterial soap, figuring that it was safer than letting her son get the flu. Writing on metaphor, Biss observed that ‘if our sense of bodily vulnerability can pollute our politics, then our sense of political powerlessness must inform how we treat our bodies.’

The fear of the external goes a long way to explaining vaccine hesitancy. Biss sees this as originating in the idea that one’s body cannot be a vector of threat to others, but that it must be protected. She links this to ‘lifestyle is its own variety of immunity’; as ‘when health becomes an identity, sickness becomes not something that happens to you, but who you are.’ Those with the financial and social capital to flaunt juice-cleansing lifestyles are less likely to become sick in the first place. People that are traumatised from abuse or poverty are more likely to develop chronic illnesses, and have less access to treatment.

The human body is not a border, and ‘nature’ is not only something we engage in on a bush walk. The separation of human from the rest of the living world has paved the way for colonialist exploitation and misuse. What we conceive as ‘natural’ in terms of health is the privileged half of the natural/synthetic binary. The fallacy is that what is natural must be always better and safer.

That is not to discount that there are dangers in the world. There are indeed pollutants to be concerned about, but these are so ubiquitous at this point as to be completely unavoidable, especially in areas where compromised water quality is par for the course. As microplastics turn up inside human tissue, we don’t seem so far from fish with guts full of plastic bags. Nothing is thrown away that doesn’t return in the air, in the water.

Porousness

In Beyond the Periphery of the Skin, Silvia Federici states that ‘with the development of capitalism, not only were communal fields “enclosed”, so was the body’. She writes of ‘the militarisation of everyday life’ which supports capitalism, including the techniques of mass incarceration ‘and the proliferation of detention centres for immigrants.’ We understand ourselves as discrete units that produce surplus value through our labour, which is then siphoned away. We are separate from each other, and define the human world in opposition to what we conceive as ‘natural’, though this is a false dichotomy.

It is language that creates the division of self/other, in/out. The language of immunity with its militaristic understanding of self and other is used to support torturous policies of imprisonment and exclusion. To resist this isolating understanding of people, community, and the world, Federici draws on the philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s ‘grotesque body’ –

a body radically open to the world both temporally and spatially, simultaneously eating, shitting, fucking, dancing, laughing, groaning, giving birth, falling ill, and dying.

Federici argues for a more porous understanding of bodies, one that allows the external to flow freely through. To allow for transformative encounters, exchange.

When police threatened protestors with move-on orders, they took up space, dancing while socially distant. A woman stood in front of the gates and told the story of her son who died in off-shore detention. One of the men imprisoned inside the Kangaroo Point hotel was wearing a heavy metal shirt on the day of a protest. People threw up metal hand signs for him. One day, not long after, I heard a song of his played on 4ZZZ as I drove around the suburbs.

There are other ways of knowing and being, and they exist outside the airless framework of the colony.

Image: Luis Jiménez Aranda, La visita al hospital (1889)