If, like 10-15 per cent of the global population, you have been diagnosed with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), you are likely female and young.

If your symptoms remain unresolved despite your best dietary restriction efforts, immediately request referral for non-routine testing. You may have an undiagnosed illness – because your pain has been sold to you as a product of ‘stress’. Rather than revolutionising healthcare, the recent turn in medical research to complex mind-body connections is unwittingly returning us to the dusty psychiatrist’s couch of the early twentieth century.

In other words, you have just been diagnosed with hysteria.

*

Around the end of 2019, I suddenly began experiencing deep stomach pain, digestive dysfunction, poor sleep, and was constantly cold-ridden. At dinner I would watch boiled peas fall off my violently shaking fork.

I went to the doctor. His response was that ‘it just happens sometimes’. However, he would run blood tests for ‘everything’.

The tests came back negative. I was diagnosed with IBS and chuted back onto the street, armed with a pamphlet of symptom clusters and advice on dietary solutions that directly contradicted one another.

A year and a half of persistent searching later, I scanned positive for endometriosis, a condition projected to occur in 10-15 per cent of women. Without surgery, I risk kidney failure. What had really happened in that first doctor’s office?

*

IBS is typically treated as a psychosomatic disorder – that is, a condition in which psychological stress expresses itself through physical symptoms. These symptoms in turn cyclically cause mental stress. In IBS, psychological stress disrupts signalling between the brain and digestive system. Consequently, the digestive system becomes chronically dysfunctional.

Studies also suggest other causes for the disturbed mind-gut signalling, such as infection, food poisoning or antibiotics. However, not once in my hunt for a diagnosis was this mentioned by any of the multiple doctors I saw in both England and Australia.

Presented with a twenty-year-old woman in distress about a sudden onset of deep stomach pain, not a single doctor intimated a cause other than stress, or emotional dysregulation. Later, as symptoms worsened, I was diagnosed with ‘probably mild depression and anxiety, common in people your age.’

I certainly was visibly distressed – I was experiencing constant, inexplicable pain.

Thus, the first problem with an IBS diagnosis: did stress cause my physical symptoms, or did physical symptoms cause my stress? Research in psychology and biology increasingly demonstrates the gut’s role in regulating most bodily functions, from healthy sleep patterns to the nervous system, and thus conditions such as depression and anxiety. Perhaps, as my gut ran wild, so did the rest of my body, inducing my cycle of sleeplessness and emotional fluctuations. My deep fatigue, for instance, which was actively contributing to my difficulty in regulating emotions, is recorded ‘in over 60% of patients with IBS’. In short, there was actually no way for the doctor to establish that it was the stress causing the physical problems, rather than the other way around.

Since research into IBS and the mind-gut connection is so new, it is impossible to know which is the symptom and which the cause. The practitioner who diagnoses stress-induced Irritable Bowel Syndrome is therefore assuming that it is the stress causing the pain. Medically, a ‘syndrome’ is precisely not a causal diagnosis, but the identification of a symptom cluster.

So, what drives a doctor’s assumption that a patient whose symptoms cannot be explained by routine tests is stressed – rather than referring them for non-routine tests? I’ll seed a clue: two thirds of those diagnosed with IBS are women.

The relationship between the mind (psyche) and body (soma) is simultaneously at the cutting edge of biological and psychological research and old. Medical practice has a long history of explaining women’s health problems as a result of emotional dysregulation. As the International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders puts it, ‘IBS is a major women’s health issue’. Like other little researched chronic illnesses, IBS has become ‘a women’s dilemma’ because it’s mainly diagnosed in women.

The social reflex of connecting women’s health problems to an innate gendered limitation is most controversially remembered through hysteria. Like IBS, hysteria is psychosomatic, relating states of psychological stress – according to Freud, forgotten traumas – to seemingly inexplicable physical symptoms.

The word hysteria derives from hysterikos, meaning ‘of the womb’, and was coined by Hippocrates to describe ‘a cluster of ‘feminine’ complaints’ including ‘bad moods, seizures, and morbid thoughts.’ Hysteria has undergone many iterations as a way of medically explaining the persistent social connection between femininity and weakness. Because the medical standard remains masculine – contemporary medical research is mostly conducted by men, on men – confusing symptoms seem inherently feminine.

This connection between mysterious illness and female weakness is indeed being made in female IBS patients, or women whose stomach pains are not easily explained by testing standardised on male bodies: 47-55 per cent of women diagnosed with IBS have received unnecessary ‘hysterectomy or ovarian surgery’.

A number of young women I interviewed in the course of 2020 confirmed that my experience remains unexceptional. One interviewee contracted Lyme disease and was informed instead that her symptoms were due to stress from starting university. Advised to try a low FODMAP diet, which is prescribed to IBS patients, she was only tested for Lyme after her brother and mother also began showing symptoms. Another, also wracked by endometriosis symptoms for over six years before diagnosis, was, over time, sent to a psychologist for anxiety and depression, diagnosed with chronic pain, and then diagnosed with ‘non coeliac gluten sensitivity, lactose intolerance and IBS’ when a specialist couldn’t find anything wrong.

The point is not that the doctors who saw them or me were vicious misogynists, but that IBS is too convenient a diagnosis. IBS’ symptom-led definition is so broad that it can be diagnosed in anyone presenting stomach problems. IBS thus enables a harried doctor to neatly resolve a complex case. When we have to make a decision quickly, or are tired, our ability to self-reflexively monitor thoughts is limited. Stereotypes exist exactly for these moments: pre-existing narratives about people and events enable us to make quick interpretations of scenarios and thus come to rapid decisions when we need to.

So, a doctor who is tired or has little time between half-hour appointments will, without realising, lean on historical perceptions of their patient to draw medical conclusions. If that patient is an emotionally distressed young woman with stomach pain, whose routine testing suggests perfect health – then it seems entirely reasonable, as IBS proposes, that her physical symptoms are caused by nothing more than her own stress.

However, the cost of a hysteria diagnosis can be direct damage – and not only because it allows us to fall back on dismissive stereotypes of the female condition rather than providing, as it could, cutting-edge treatment. Critically, the ease with which IBS fuels gender stereotypes by being new and under-researched is circular: as women are more likely to be diagnosed with IBS, the condition is relegated to a ‘women’s issue’ (like Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and endometriosis), and falls further down the list of research priorities.

Yet, the final and most important twist of the psychosomatic diagnosis is that it puts the onus of the problem on the patient: since they developed the physical symptoms due to stress, the illness is effectively their fault. They’ve overestimated their work capacities. They are bad at managing stress. They are somehow mentally weak. The focus of treatment and seeking solutions thus becomes their own responsibility: they are the ones who have to develop better stress management strategies and follow a series of highly restrictive diets to figure out if there are ‘trigger’ foods that are causing the stomach pain. If diets don’t work, then the only recourse is indeed a reinvention of Freud’s hysteria solution: an experimental $100 hypnotherapy app.

When a patient actually has an undiagnosed illness that is presenting through a confusing array of gut-related problems, the convenience of the IBS diagnosis becomes harmful. Missed diagnoses are happening to a significant proportion of the population diagnosed with IBS. For instance, Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth, or SIBO, is present in 30 to 85 per cent of IBS sufferers. SIBO requires specific treatment, in the absence of which, complications pile up. Given the breadth of IBS symptoms, SIBO and IBS have overlapping symptomatology to the extent that it is impossible to know if this 30-85 per cent have IBS at all, or if one caused the other, or both by something else, such as endometriosis. In this light, does the high population prevalence of IBS indicate the commonness of the illness, or that many other illnesses are captured by its broad symptomatology?

Consequently, routine testing before an IBS diagnosis needs to be expanded, or followed by immediate specialist referral for non-routine testing. This simple change would provide two-fold benefits: at baseline, the instatement of procedural checks is how a medical institution can mitigate misdiagnosis informed by deeply embedded stereotypes. The treatment of ‘women’s dilemmas’ as standard procedure would also lower cost barriers to treatment – specialists and testing for SIBO, not being routine, are not covered by Medicare and incredibly expensive.

My goal in opening my pain to public scrutiny is pragmatic: it is to urge others struggling with an IBS diagnosis to seek further healthcare. So, if you have been diagnosed with IBS, you’ve tried the doctor’s recommendation of dietary changes, and ultimately, wearily, you’ve seen little result – request a referral to a specialist. This may not be the end of your search for treatment, but it will be a better start than a hysteria diagnosis.

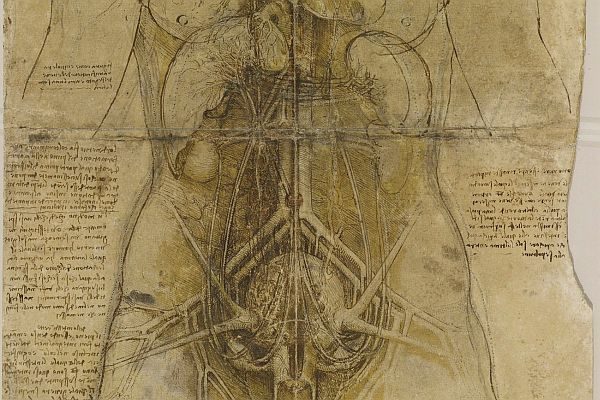

Image: Leonardo Da Vinci, The cardiovascular system and principal organs of a woman (detail) c.1509-10