I am a survivor of the compulsory mental health system. I have experienced or witnessed the range of indignity and violence it enacts.

Forcible apprehension by armed police. Physical restraint to a gurney by the arms and legs. Injections with tranquilisers and antipsychotics against a person’s will. Being force-fed handfuls of medications a day, as if that could solve frightening experiences that won’t seem to abate. Involuntary electroconvulsive treatment (ECT), with all the trauma that comes with that experience, even though when this ‘treatment’ was first developed brain damage was essentially its aim. 24-hour arm’s length nurse observation for months at a time, even in the shower, toilet and while sleeping. Being locked in ‘seclusion’, a small bare space with nothing apart from hospital pyjamas. Experiencing long-term homelessness and being kept inside secure prison-like spaces for years simply because you have nowhere to go. Extended community treatment orders where treatment is also compulsory, where if you miss a fortnightly antipsychotic injection it’s straight to hospital again – escorted by police, regardless of your consent.

*

The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System handed down its mammoth final report in March. It did so after two years of consultations, hearing of evidence and consideration by four commissioners, none of whom have a lived experience of emotional distress or psychiatric diagnosis.

The report recommends broad reform of the system, that is, the way people access assistance – for example through new community-based local hubs, for people who currently can’t get access to acute services because their distress is not deemed ‘serious enough’. It also recommends new approaches to dual diagnosis treatment, integrated partnerships between health, housing, financial, legal and other services to address the holistic needs of people in distress, stigma education, and greater involvement of carers and family, among many other measures.

Implementation will change the service system significantly. But the report changes very little about the structures underlying the mental health system.

The report makes sixty-five recommendations, in addition to the nine from the interim report. Some of these are positive, but many will reproduce the power structures and denial of self-determination the current system depends on. In particular, the report recommends ‘reduced reliance’ on compulsory treatment, which includes the use of non-consensual medication, ECT, enclosure in locked wards (including ‘high dependency’ units where access to open space, stimulation and visitors is even more restricted and where surveillance is even more intense), and community treatment –where the person lives in the community but still has to comply with directions of their psychiatrist.

New legislation enshrining this approach is yet to be enacted and the Mental Health Act 2014 repealed, but it is unclear how a reduction in compulsory treatment will be achieved in reality, even if this objective ends up being protected in the new Act. The current criteria for involuntary treatment (section 5 of the Act) are:

(a) the person has mental illness [defined in section 4 as a medical condition that is characterised by a significant disturbance of thought, mood, perception or memory]; and

(b) because the person has mental illness, the person needs immediate treatment to prevent–

(i) serious deterioration in the person’s mental or physical health; or

(ii) serious harm to the person or to another person; and

(c) the immediate treatment will be provided to the person if the person is subject to a Temporary Treatment Order or Treatment Order; and

(d) there is no less restrictive means reasonably available to enable the person to receive the immediate treatment.

In the inpatient setting, the assessing doctor can make a temporary treatment order for twenty-eight days, after which the Mental Health Tribunal must review the case and decide if further compulsory treatment is warranted, either in hospital or in the community. This is determined based on a report submitted by the treating team, as well as oral submissions by the treating team, the individual subject to the treatment, and their lawyer – if they have one.

However, the statistics regarding what actually happens at the Tribunal speak for themselves. In 2019-20, 92 per cent of orders applied for where hearings were held went ahead, 87 per cent of involuntary ECT orders went ahead, and only 13 per cent of patients did in fact have legal representation.

The current Act already requires that compulsory treatment only be ordered if there is no less restrictive way or environment within which to provide the treatment. In practice, however, this requirement is a formality. It is routine for involuntary treatment to be considered critical, perhaps because – in terms of the services currently available – there are few other options. In the community, it is common for treatment orders to be renewed for years on end every time they expire.

The existing Act also sought to redress the power imbalance between psychiatrists and patients by promoting ‘supported’ rather than ‘substituted’ decision-making. This has failed. The Royal Commission’s recommendations appear again to go in this direction, but obvious structural barriers exist when treating doctors are enculturated into the persistent view that almost all patients lack capacity. New accountability measures recommended by the Royal Commission seem weak and are unlikely to affect the providers of compulsory treatment.

It remains concerning that, in practice, doctors can make orders without oversight for a month, the Tribunal confirms the doctors’ decisions in the vast majority of cases, and the Tribunal finds there is rarely any less restrictive treatment available. The sort of training proposed by the Mental Health Tribunal and recommended by the Commissioners is as unlikely to help as has the ‘cultural sensitivity’ training given to police who continue to racially profile culturally diverse communities. Provision of more community-based, early intervention and assertive outreach services may stem some need for inpatient admissions, but cannot address the overwhelming number of people seen as so acutely unwell by the system that they need compulsory treatment. This is despite the fact that there are ‘genuinely decent’ people working in the system, because their participation is underpinned by a logic and an institution that is deeply flawed. So how will the culture and practices of hospitals and doctors change?

The report also recommends the phasing out of restraint and seclusion within ten years, a measure critics have said steam rolls the human rights abuses entailed in this ‘treatment’ for a further extended period of use. The new Act could abolish these options immediately. Instead, hospital use of these extreme measures will be sanctioned for a further period. Again, it is difficult to see how doctors could be made to see that there are other options available, since the Act already requires that the decision can only be made if it is ‘necessary to prevent imminent and serious harm to the person or to another person’ or in the case of bodily restraint, in addition to the above, if it is necessary ‘to administer treatment … to the person’.

How much higher can the standard be than ‘necessary’? Yet these interventions are routinely used in high-dependency units across Victoria, usually in response to agitation and refusal to take medication rather than any risk of danger to a person.

The report also recommends that police should not be the first or primary responders to people in emotional crisis, with triple zero calls about such incidents to go to the ambulance service first where possible. But this does not rule out the use of police in these call-outs. Paramedics also use physical restraint while transporting people to hospital, so this new procedure may not be significantly less violent. And it certainly does not go as far as community-run crisis response services delivered by people with a lived experience of mental health pathologisation and diagnosis.

It is noteworthy, however, that drop-in peer-run alternatives to emergency departments will be established, as well as respite opportunities in more ‘homely’ environments also delivered by people with a lived experience. These changes, all of which have been promised to be introduced, have been lauded by some people with experiences of emotional distress, but these are not generally the people subject to compulsory treatment.

The report is mostly good news for those desperate for help. But overall, for those not seeking treatment or who resist their pathologisation, there is very little to suggest the system will be any less violent, coercive, disempowering, oppressive or carceral, or that people’s autonomy will be respected and promoted any more after implementation of the report’s recommendations.

Although the report does recommend a broader approach than just the biomedical model, there is little in it that reduces the dependence on diagnosis and psychiatry. But the violent structures of health systems have traumatised people so deeply that there is a term for the harm perpetrated by them –iatrogenic violence. According to the vision of this report, those structures will essentially remain unchanged, with thousands of people a year subjected to invasive treatment without their consent, even if it is said to be a ‘last resort’.

Currently, our only definitions of and responses to distress are ones which enact violence. Real alternatives for people who are at serious risk of coming to harm are needed, but this requires a complete rethink of psychiatry and the notion that distress is a medical issue. One place to start may be the Open Dialogue approach. This method recognises that people will not identify as needing support as long as that support is pathologised and situated within a system that violates their autonomy and bodily integrity, but rather that crisis and its resolution are ‘relational’. As Mark Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism, it may be that emotional distress is ‘neurologically instantiated’ (the chemical imbalance theory) but this says nothing about its origin, which is located in the socio-political.

We urgently need a new discourse around distress and crisis as being produced by lived social, economic and political conditions, and a public conversation about how we can genuinely support and promote the autonomy of people who may be unsafe and do not conceptualise their problems and their subjectivity as medical issues. But this is much more than the Royal Commission can or wants to do.

For people who have been subject to prolonged compulsory treatment, the Royal Commission recommendations are not the panacea others in the community perceive. We have borne the brunt of too much violence and injustice at the hands of this system to hold the hope that its structures and culture could change, or even that the Commissioners intend it to change in the way we need it to. The distress and trauma caused by involuntary psychiatric treatment is often said to be more harmful and distressing than experiences that lead people to these institutions in the first place.

As Marc Roberts puts it, we are categorised as people with severe psychiatric conditions, through which practitioners ‘invite’ us to understand and apprehend ourselves as being ‘afflicted’ by a chronic ‘illness’, which renders us unable to be autonomous and leaves us dependent on the treatment provided by mental health professionals. This is not how the system should be, but it is how it is structured to be: a system that traps people, that traumatises them, all the while claiming it is helping. To truly change it would require dismantling those structures.

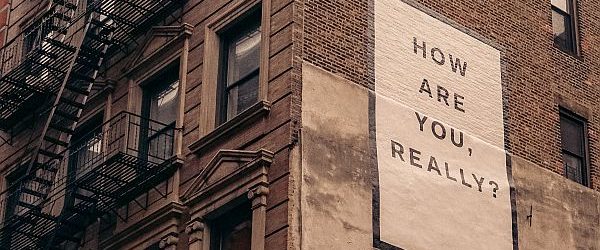

Image by Sam Cox