Spy thrillers can be something of a guilty pleasure for a leftist. In these stories, kidnapping, assassination, torture and surveillance are directed against the vulnerable and those who resist state and corporate power. You could argue that this isn’t entertainment and shouldn’t be viewed through the eyes of the oppressor. Any depiction of intelligence agencies must reckon with their destructive function within empire.

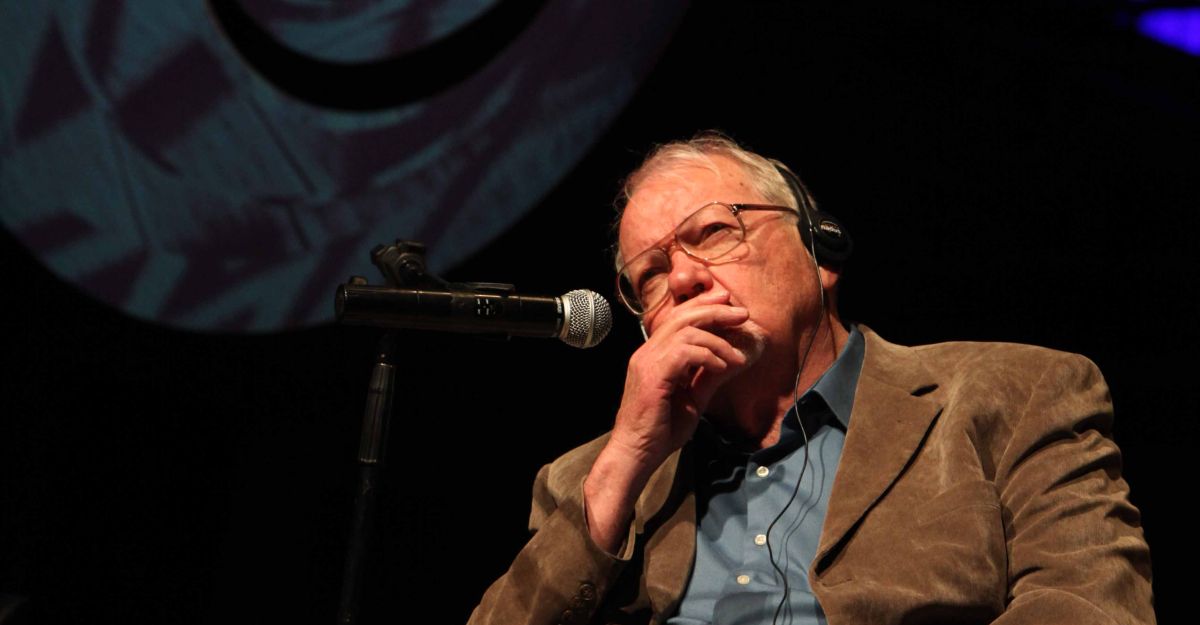

Very rarely, writers in this genre show the terror of ordinary people in the face of intelligence and security agencies. John le Carré, who died last week, was one such writer, but he also brought an insider’s critical insight into imperial management. His work helps us understand the nature of hidden power and paranoia in the century just passed, and the one in which we live.

Born David Cornwell in 1931, le Carré emerged as the great literary chronicler of the Cold War over a long and prolific career. Few others so effectively captured the deception, hypocrisy, idealism and destruction of the postwar world – and its vivid dreams of a social order that would bring peace.

Le Carré was a humanist fixated on the human cost of militarism. His novels reflect a deep cynicism about the nature of global power politics. At times he was nihilistic about the absurd waste and emptiness of his world: lies, counter-lies, manipulation, shadow games and paranoia.

His outlook was as complex and contradictory as his frail human subjects. He called himself a ‘compassionate conservative’ and vocally opposed the Iraq War. He spied on leftists at Oxford. At the end of his life, his imagination was limited to Russophobic, anti-Corbyn liberalism and superficial anti-Trumpism.

However, just like his novels, his worldview was layered, and we shouldn’t always take this master of deception at face value. Le Carré’s work is a far cry from the fairly pedestrian politics he claimed to espouse. Separated from his deeds and words, his novels reveal a gifted political thinker whose incisive human insight lets him reveal a shadowy world to us and show us who’s really in charge.

Who cares, loses

Le Carré will always be best known for his authentic, textured, human-centred depiction of Cold War espionage. His unique exposure to the spy’s craft during his time in British intelligence and his fantastic ear for dialogue make this murky, uncertain world seem as fresh today as it did in the early 1960s. He led readers into a world of tired, rumpled grey bureaucrats sending naive young idealists to their deaths in the thresher of the hidden struggle for postwar Europe.

His novels closely observed how Britain’s class system (especially through Eton and Oxbridge) turned out administrators for its crumbling empire. The uncovering of the Cambridge Five – Soviet agents who reached the heights of intelligence, diplomacy and academia – showed him this ideological training was not foolproof. Nothing could prevent dreams of a better socialist world, even among Britain’s most trusted spies. The scandal would heavily influence his seminal Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, which follows the hunt for a mole at the top of British intelligence.

Le Carré is uniquely English and lo-fi. There are no gadgets and explosions are rare. Rather, the subject matter of his books is the infinite variety of human relationships and how these interact with elite designs of political violence.

Unlike his American counterparts – whose heroes are assured and capable – le Carré’s protagonists are often fallen, compromised and flawed. Human frailty is the stock-in-trade of these spies, and le Carré held this focus even in his final book, the Brexit thriller Agent Running in The Field. Whether it’s debt, a rocky marriage or feeling underappreciated in your job, ‘everyone has something. The job of the recruiter is to find it!’

One of the greatest sins in le Carré’s world is to dream of something better, as this exposes you to manipulation – like the young leftist actress recruited by Mossad to infiltrate a Palestinian terror group in The Little Drummer Girl. Idealists, lovers and naïfs rarely see their hopes made real. The only people putting their vision into practice are the cynical manipulators in Whitehall and the Kremlin who dream of endless shadowy war. No-one else is allowed to dream for long.

In The Looking Glass War, a celebrated aviator reduced to a desk job is lured with dreams of redemption to a mission in East Germany, and certain death. The MacGuffin he was sent to find –Soviet missiles in Eastern Germany – never existed. The senseless deaths of the agent and the East German border guard he brutally murders have no redeeming virtue or strategic significance to Her Majesty’s Government. They are more screams in the dark in an irredeemably meaningless conflict driven not by principle but by the age-old struggle for geopolitical influence.

This is often how le Carré pawns end: their quixotic missions are revealed as absurd, but only when it’s too late. Sent on a goose chase or pursued to the ends of the Earth, his protagonists are always the last to know. Only when their worlds start collapsing do they see that they weren’t as much in control of their lives as they thought.

The spy who scammed me

After the end of the Cold War, le Carré transitioned seamlessly into the new unipolar world at the end of history. The grimy moral indeterminacy of East-West subterfuge became the search for sanity in an increasingly terrifying world of terrorism, the expanding security state, and the sinister global reach of corporations.

Two of his novels focus on the political function of lies and liars. Absolute Friends opens with middle-aged former student leftist, now destitute ex-teacher Ted Mundy working as a self-employed tour guide at a castle in Bavaria. He scams clueless tourists with ‘illicit improvisations’ about German history after making sure nobody is recording him. Set against the invasion of Iraq and the growth of the security state in the wake of September 11, Mundy’s soliloquies about the history of kings stand in for the power of a bold, confidently delivered lie to sway a compliant media and a distracted public.

Predicting the rise of spies as a consultant class of grifters, The Tailor of Panama follows a scam artist and gifted storyteller whose life rests on a series of lies and who becomes useful to British intelligence by spinning total fabrications. Everyone from his handler to the senior bureaucrats have their snouts in the trough, so no-one looks too closely as his lies bring the situation closer to war. As the demands for intelligence escalate, his story must get taller until it precipitates a US invasion.

Tailor eerily predicted the runup to the Iraq War, in which a series of sleazes and addicts like the CIA asset ‘Curveball’ provided the gossip that ultimately formed America’s case for war. In The Loop – another brilliant satire of Britain’s destructive secret role in world affairs – features a similar plotline, in which an intern’s arguments against invading Iraq are cut from a crucial document, and her arguments in favour are passed off as hot intelligence.

Le Carré shows us the propaganda function of intelligence. If the political will is bent towards militarism and imperialism, then any data pointing against those outcomes will be carefully excised from the finished product, leaving only useful lies.

#NotAllArmsDealers

Occasionally a le Carré novel just has bad politics. The Night Manager follows a veteran recruited by the British Government to bring down an international arms dealer. The premise is that England – in reality the world’s second-largest arms exporter with £11 billion in sales, one third of which go to authoritarian states like Saudi Arabia for its genocidal war in Yemen – doesn’t like the international arms trade and wants to stop it.

It’s a rare goofy step and a shockingly misjudged conceit for a novel, based on an apparent residual belief in the goodness of Britain’s international mission which is thankfully largely absent from the bulk of his work.

Le Carré today

The state’s use of informants and agents provocateurs cuts at the social fabric that lets people trust each other and build movements. Spies are instruments of geopolitical influence wielded against weaker countries and perceived overseas threats. They are scouts for empire, and witch-hunters tracking dissidents and exiles abroad. Though le Carré sometimes fell short of fully understanding this function, he remains a vital literary authority on the covert application of state power. His key insight is the vulnerability of virtuous, principled people to recruitment and exploitation in the malicious designs of the powerful.

As sabre-rattling escalates and increasingly hysterical claims of foreign influence are used as pretexts for military build-up – in Australia and elsewhere – John le Carré’s novels will not stay in the last century. They will remain as prescient and timely as ever, and only become more essential to our understanding of how secret power is wielded against the forces seeking a more just world.