When historian Geoffrey Serle first coined the term Anzackery, in 1967, he did so to question the notion that the Anzac legend and other features of modern Australian nationalism would suffice as the ingredients of a new national identity in the wake of Empire. The use of Anzac history and imagery as a means to forge a new team identity is a prominent theme in the much-vaunted recent documentary series The Test: A New Era for Australia’s Team. In the opening minutes of the first episode, viewers are provided a brief description of mateship by former captain Steve Smith, his words accompanied by a sweeping view of Anzac Cove at Gallipoli. The symbolism is obvious: here is an Australian team determined to clothe itself in the spiritual garb of the ‘Anzac tradition’ in order to embody a sheer, essential ‘Australianness’.

This was a team caught cheating in the most brazen way in South Africa in 2018, an episode widely regarded as a slap in the face not only to the games’ rules but also to the Australian sense of ‘fair play’. The television series is an attempt to ‘win back’ the Australian public after the fallout of the sandpaper scandal. Its narrator even tells us that ‘this is a story of hope, faith, and belief: the long and difficult journey of trying to revive and rebuild the pride of Australia’. Redemption, then, is the key theme of the series, and to do this the team has predictably turned to the past and traditional tropes of national identity.

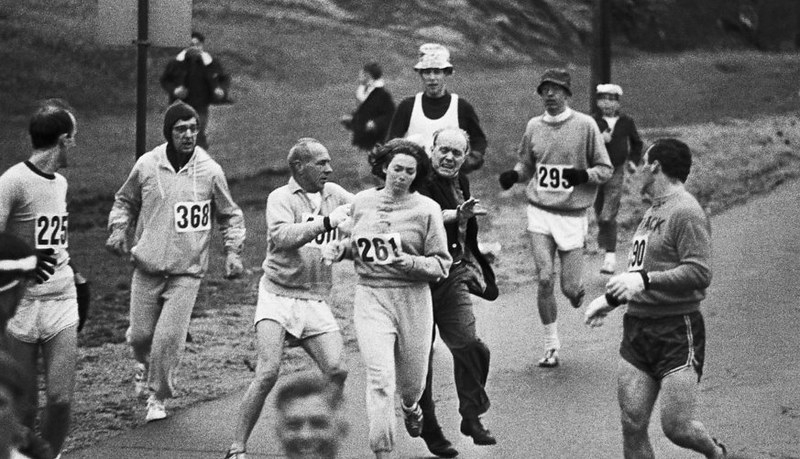

However, this is by no means the first time an Australian cricket team has invoked Anzac. In 2001, then-captain Steve Waugh famously took his touring side to Gallipoli ahead of the Ashes series, even re-enacting a photograph of an impromptu game of cricket held there in 1915, replete with team members donning slouch hats. The gesture was at best cheesy, at worst tasteless, but the symbolism of the photograph is hard to miss – an attempt to demonstrate that the team were cut from the same Anzac cloth and that, while the job they were on their way to do in England could never compare to that done in 1915, there was a spiritual connection between them. The tradition was continued by Ricky Ponting ahead of the 2005 Ashes when he took his side to key battle sites on the Western Front, including Villers-Bretonneux and Pozières.

In the early hours of the morning before the 1999 World Cup final, in which Australia faced Pakistan, Waugh had penned a poem to inspire his players which drew upon the Anzac legend:

So let’s make a pact to fight as only we can

And show the ANZAC spirit where it all began/It will be a time we’ll never forget

And one where we can all say I’ve got no regret.

Around the turn of the century, then, and at the very same time that prime minister John Howard’s own embrace of Anzac was in full swing, Waugh had begun to consciously instil in the Australian cricket team not only a desire to publicly pay homage to the Anzacs – engaging in performances like the photo re-enactment – but also the belief that their respective journeys to Europe, and to character, overlapped.

This is a viewpoint echoed by fast bowler Pat Cummins in The Test. Reflecting on the team’s visit to Gallipoli in 2019, he notes:

So many people talk about the Australian culture and their identity being founded in that Gallipoli campaign – we were just newly federated. It kind of felt like a link to us players. We’re a newish side going off overseas, trying to find our identity. We didn’t have to look too much further than all the great traits a lot of those diggers had over there.

Cummins is essentially claiming that this scandal-hit team, desperate to forge a new identity, is following in the footsteps of the Anzacs not in deed, but emotionally and psychologically. Over the course of eight episodes, the viewer is subjected to a barrage of predictable lines about ‘making Australians proud of us again’, ‘being good Australians’ and embodying Australian values. The first shot we see of the Western Front battlefields during the current side’s visit there in 2018, for example, is of a cross draped with the Australian flag at Pozières. Justin Langer goes on to explain that ‘all those things that we know about being Australians – that Anzac spirit – wasn’t lost on us … We’re actually representing Australia here.’

This sets the tone for the entirety of the series. Tim Paine’s verbal jostle with Virat Kohli during the 2018/19 series against India becomes ‘Anzac banter’, according to Langer. ‘Mateship’, too, is given a repeated airing. In one of the most bizarre moments of the show, the term melds with corporate jargon as Paine presents a slideshow entitled ‘Our Expectations’ featuring the qualities deemed essential to the new-look side. All are prefixed by the word ‘elite’, so we have: ‘elite honesty’, ‘elite learning’, ‘elite humility’, ‘elite professionalism’ and – yes – ‘elite mateship’.

In an effort to escape the derision of 2018 and its aftermath, the team has turned to a familiar and time-tested Anzac motif, but it only serves to reinforce a team ethos that is poorly defined and shrouded by platitudes and management-speak. Reaching into war’s back catalogue in search of redemption means that a fresh, unique identity heading into this so-called ‘new era’ of Australian cricket remains elusive.

The Test is a PR exercise and its omissions are predictably glaring. Most notably, the issue of what actually led this immensely talented team to cheat in South Africa and the ongoing questions associated with it are never addressed. Instead, the viewer is taken through a tediously familiar narrative, littered with Anzackery and generalised notions of what it is to be ‘Australian’ as the team charts a heroic path from despair to triumph in the space of little more than a year.

The real merits of the documentary are the behind-the-scenes look at players’ reactions to the ups and downs of the game while it is in progress. And therein may lie the message: that it might be time to just get on with the game and set an example through on-field actions, rather than constant appeals to team ‘culture’, ‘identity’ and ‘values’. After all, this is the same team that failed to live up to these ‘Australian values’ in 2018 which they now present as central to the ‘new era’. The reality is that the ‘new era’ is nothing more than a return to the belief that Australia’s cricket team ought to reflect a set of wider, supposedly ‘national’ values. The Anzac legend again serves as a crutch for the team to lean on, providing the spiritual substance on which it sets out its stall.