Dr Debbie Bargallie’s Unmasking the Racial Contract: Indigenous voices on racism in the Australian Public Service irrupts into the socio-political climate with urgency. Based on Bargallie’s doctoral research into systemic racism experienced by Indigenous employees in the Australian Public Service (APS), the book employs critical race theory to examine discrimination and disproportionately low career outcomes of Aboriginal staff.

Unmasking the Racial Contract is motivated by the author’s own experiences and is framed by detailed interviews or yarnings with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers. There is an unrelenting hopelessness to these stories, but Bargallie’s method is designed to incite change.

In the foreword Dr Jackie Huggins AM describes reading it as if it were her own biography and many First Nations and PoC readers may feel similar. Yet the book’s strength lies in its ability to unsettle white privilege and the invisibility of racism in workplaces like the APS. This is achieved by exposing the ‘racial contract’, a concept advanced by Jamaican academic Charles Mills to illustrate how social and moral contracts are not neutral but rather theorised by white philosophers unable to recognise their white supremacy as a political system. References to pivotal Blak and PoC authors feature heavily, creating a reciprocity that strengthens the argument while simultaneously addressing racial exclusion in the academy. Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson, Bronwyn Carlson, Sarah Ahmed, Frantz Fanon among others forcefully echo through to both affirm Bargallie’s theoretical position and highlight her indebtedness to these writers and thinkers.

Articulating my own response to this astute account was unexpectedly challenging. It was disorientating to witness the ease to which racism is permitted in institutions like the APS, whose reputational appearance is based on diversity and inclusion. The racism experienced by the 21 participants feels dismally ordinary, making it difficult to imagine change and equally infuriating to accept that these stories still exist, and that books like this still need to be written. But in 2020 racial equity both professionally and personally remains imbalanced. It enters an environment where racial injustice persists occasionally gaining traction when mainstream consciousness is reawakened by global phenomenon but unable to see the racism that surrounds us. As Amy McQuire attests: ‘Australia is outraged at police brutality in the US, but apathetic to the lives of black people in their own country.’

McQuire’s reflections are an important entry into Bargallie’s research, which exposes white Australia’s misinterpretation of racism and the erasure of everyday racism and racial micro-aggressions. As Bargallie writes, ‘a common misinterpretation is to think of racism only as acts of extreme violence perpetuated by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan – rather then the more subtle, hidden and everyday racism.’ This enables a workplace culture that ignores the impact of casual remarks or the exclusion of Aboriginal opinions and values because they are very rarely understood as racist. One of the most unsettling aspects of the book is the cumulative effect this treatment has on Aboriginal staff exasperated by white employees’ inability to interpret it as racism to begin with. This gives way to workplace environments where NAIDOC morning teas and reconciliation working groups are familiar markers of progress while the inequitable treatment of Aboriginal staff remains invisible.

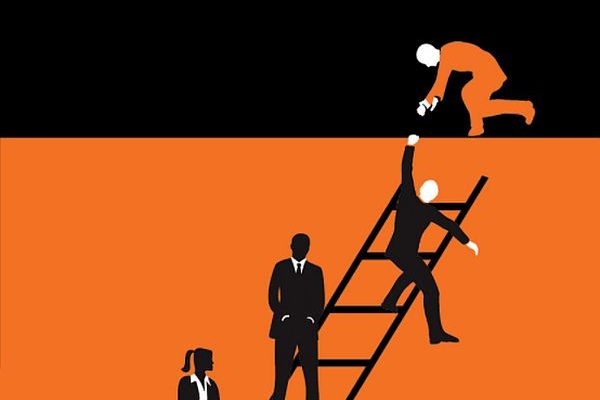

As well as suffering all sorts of daily indignities, the Aboriginal staff interviewed rarely achieved their personal and professional goals. Many left or remained in lower-rung roles with poor job satisfaction. They had overwhelmingly entered the public service with the desire to make a difference but were rarely empowered to turn it into a reality. Many associated their employment with tick box-diversity schemes, without a commitment to genuine investment in their careers.

Bargallie acknowledges the bleakness of these accounts but explains that she ‘wrote this book to break the silence on racism’, a necessary step to dismantle the Eurocentric approaches to Aboriginal employment in the APS. Finishing the book left me with an overwhelming compulsion to distribute it amongst the problematic institutions I know but was equally conscious that Blak and POC writers were starting to question whether this consciousness raising is sufficient to deliver transformative change.

This uneasiness is articulated in Alison Whittaker’s searing essay So White So What, which argues that white audiences often consume Blak texts for cultural capital or to appease guilt rather then deeper introspection and action. Whittaker describes for instance the superficial responses to Professor Aileen Morten Robinson’s Talkin up to the white woman, writing that ‘twenty years after the book was published, the vague and dripping over-praise of the work I get from non-Indigenous lovers is a turn-off, and the speed at which they devour it is not at all believable. Patronising. A flip through.’ The thought of white readers ‘flipping’ through Unmasking the Racial Contract as organisations repeat the ineffectual diversity strategies meticulously detailed is a bleak reminder of the enormous work required to break the cycle of racism in this country. But Bargallie is acutely aware of the effort required to support the canon of critical race texts. Rather then remaining static, these works often feel part of a continuum or call to action emphasising the critical weaknesses of employment programs and approaches to defeating racism.

In a recent article for The Conversation, Bargallie questions the Morrison government’s announcement that it would promote Indigenous Australians to top rank positions in the APS, arguing that it ‘may be well-intentioned, but it is also one in a long line of attempts to boost Indigenous employment.’ She concludes: ‘Structural change is also necessary. This requires non-Indigenous leaders relinquishing their automatic right to power and control – adopting principles of solidarity to work with us, not against us.’ These are the values our workplaces should aspire to rather then the image-focused strategies of diversity quotas that project progress while hiding systemic prejudice.

As I write this review, Scott Morrison’s words echo in the background, announcing his administration’s latest Closing the Gap agreement. With the experiences of Bargallie’s interview subjects firmly etched in my imagination, I find it difficult to accept how these fatigued government initiatives consistently ignore the structural change required. Would the gap begin to close if a significant number of Aboriginal people were empowered into meaningful high-paid careers with decision making power in the APS and other institutions? I think it would, but in the meantime it remains open, just as the failure to resolve the debilitating impacts of racism and inequitable power distribution continues. Bargallie’s book is a significant archive into the lived experience of workplace racism and demands reading. First Nations people will find respite in the collective affirmation that structural racism is violent even when it’s rendered invisible under the facade of reconciliation plans and diversity agendas. I hesitate to predict its impact on white readers but cling to the hope that its words will unsettle their entitlement and challenge the inaction encapsulated by that oldest of phrases in the Anglo Australian vernacular: ‘I’m not racist but …’