In one image, the ornate shopfronts of Collins Street are boarded up, while the Paris End of Melbourne appears under siege. Guarding the thresholds are groups of men. From the detached standpoint of nearly one hundred years later, we can admire the noir appeal of their fedoras and formal suits. In another, equally grainy photograph, a large crowd flees from several uniformed men.

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

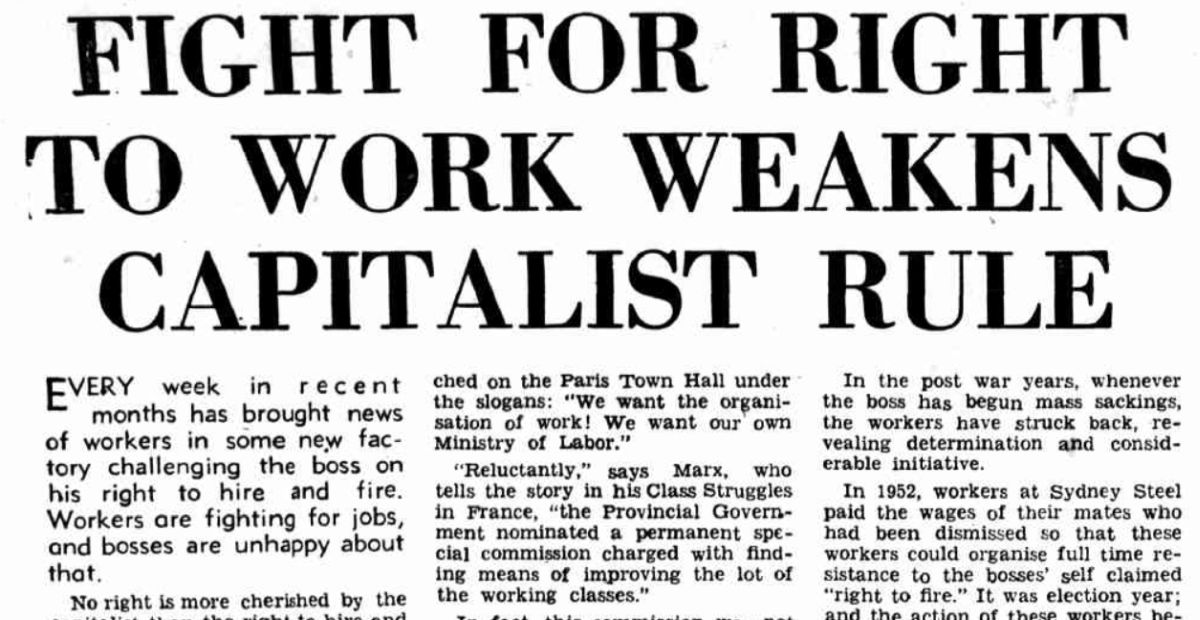

Dating from 1923, these and other photographs were taken during Victorian police strike, a protest that virtually shut down the centre of Melbourne for almost three days.

It was – and still is – extremely rare for members of the police to be the ones standing behind the picket line. In the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, with the police the very target of protest, the idea seems particularly foreign.

Yet the scenes themselves have the pull of the familiar. Depictions of civil order barely maintained by the protectors of private property. A brave few exerting control over the throng. You could easily picture the uniformed men parting the crowd in high-vis, and wielding tasers rather than batons. But the photographers and newspaper editors who selected the pictures for print, weren’t falling back on decades of conventions on photographing protests. In the early 1920s, Australian press photography was still very much finding its feet.

While other important labour protests around that time, such as the 1917 New South Wales Strike, were set both inside and outside of Australia’s largest cities – in railway yards, harbours, mines and the surroundings of other industrial workplaces – the Victorian Police Strike was set entirely against the backdrop of a modernising city. Coinciding with the rise of press photography, it offered Australian newspapers the opportunity to further capture disruption unfolding in an urban setting, where the vast majority of protests take place today.

The coverage focused keenly on visual spectacle – especially scenes of seemly reckless violence and public nuisance. The recognisability of the themes, subjects, and even composition of many of the Victorian Police Strike photographs suggests a traceable lineage.

If we are currently seeing the twilight years of printed newspapers in Australia, the early 1920s was the start of its peak. By 1923, twenty-six capital papers competed for readers. As academic Sally Young writes, many publishers had been reluctant to warm to photograph, which broadsheet papers initially viewed as a populist medium. However, by the start of the decade photographs were increasingly taking up space in the papers. Launched a year earlier, in 1922, The Sun News-Pictorial featured the office cat on its first pictures-only front cover, evidence that the ubiquity of ‘cute cat’ photographs is also not a new phenomenon.

While press photography was beginning to come into its own, another profession was on the brink of crisis. Police of this era were underpaid, received no pension or overtime, and – in Melbourne – were crammed in shabby rooms in the Russell Street barracks. Their inexperienced chief commissioner, Alexander Nicholson, was widely disliked. Many officers believed he owed his appointment to friends in politics.

Tensions only increased when Nicholson enlisted special supervisors – plain clothed ‘spooks’ – to spy on constables on the beat. On All Hallows’ Eve, twenty-seven constables refused to attend to their duties until the spooks were removed. A few days later, at the start of the busy spring racing carnival, over six hundred officers walked off the job. Former Overland editor Jeff Sparrow describes what unfolded over the Friday night in his book Radical Melbourne:

The news of the strikes brought thousands of curious Melburnians pouring into the city. For the most part, they shared the striker’s hostility with the scabs … In Swanson Street cars lined up bumper to bumper, as the angry crowds chased police on point duty back to the Town Hall, which then remained in a virtual state of siege for the rest of the evening … Police used high pressure hoses in an attempt to clear the Town Hall doors, before resorting to baton charges at 9:00pm.

Professional photographers descended upon the crowd. Images of the loyalists and strike-breakers dispersing and charging at the crowd dominated the papers.

Newspaper accounts characterised the crowd as ‘drunken’, ‘maddening’, preying on those attempting to restore order. Pictured raising his fists to an opponent, a loyalist sailor was described by contrast as having made ‘a plucky attempt to clear the streets at the height of mob rule.’

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Images of shopkeepers clearing up broken windows soon followed, as looters took advantage of the turmoil. At a time of economic crisis, at least thirty department stores, jewellers and other traders were raided.

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Like most other newspapers, The Age was quick to blame the looting on the city’s criminal element, reporting:

If the mutinous police had any public sympathy before Saturday, they have none now. Their only friends are the hoodlums and criminals. All decent-minded people stand aghast at the display of vandalism and crime which took place on Saturday, and for which the mutinous police must take full responsibility.

As it transpired, most of those arrested were actually ordinary working people. Moreover, as Sparrow writes, ‘the majority of injuries were not from the mob turning in on itself, but from the forces protecting private property.’ Nearly two hundred people were taken away by ambulance following police baton charges.

In the digital age, where a virtually limitless number of images can be taken of any given event, we see a similar media representation of participants as an angry or aimless crowd, or images that paint them as thugs and opportunist lawbreakers. Say, youths atop a police car or setting it on fire.

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Yet violent images of protest are sometimes counterbalanced by the visual documentation of moments of kindness, strength and community. In the case of the Victorian Police Strike, there is one exceptional photograph. Taken soon after an early strike planning meeting, it was published in The Argus on 3 November 1923 and depicts the officers as looking hopeful, even jubilant.

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

Courtesy: National Library of Australia

While none of the 636 police officers dismissed from the force were ever reinstated in the aftermath of the protests, authorities did largely concede to the organisers’ demands, bringing their wages and conditions near the levels of to their colleagues in New South Wales.