Explaining the politics of the Clash, lead singer and chief lyricist, Joe Strummer, stated: ‘I think people ought to know that we’re anti-fascist, we’re anti-violence, we’re anti-racist and we’re pro-creative. We’re against ignorance’ (New Musical Express, 11 December 1976). In the lyrics for the band’s first single, ‘White Riot’ (CBS, 1977), Strummer implored white people to learn a lesson from black people by collectively standing up for their rights. And, although he did not say ‘black and white unite and fight,’ it was clear he meant black and white people should together fight their ruling elites. He and the Clash did their best to make good on this anti-racist commitment during their first and only tour of Australia, some six years later in 1982.

As well as having Aboriginal band No Fixed Address open for them at one gig, the Clash did this by agreeing to have veteran Aboriginal rights activist, Gary Foley, speak at many of their shows during playing their version of the Willi Williams’ song, ‘Armagideon Times’. Foley was an internationally recognised Aboriginal rights activist known for his work in establishing the Redfern Aboriginal Legal Service and the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra. Alongside a number of other Aboriginal activists such as Isabel Coe and Dennis Walker, Foley organised against state and federal policies which made Aboriginal people foreigners in their own land, and called for Federal Parliament to recognise First Nations sovereignty.

Playing ten gigs in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney in February of that year, the Clash had a stop-over in Sydney on their way to play four shows in New Zealand and before coming back to Sydney to start a seven-date residency at the Capitol Theatre. The band held a press conference during their stopover to publicise the residency, their tour and their politics.

There are different, somewhat conflicting accounts of what happened before the Clash left for Auckland and after they returned to Australia. In the official band biography The Clash, bass player Paul Simonon told of staying at Sydney’s Sebel Townhouse Hotel and being

woken up by a knock at the door. Three Aborigines were standing there, wanting a chat. They asked if they could come up on our stage to talk about their situation. So, I got Joe and we had a meeting and, of course, said yes. We realized the power that we had ‘cos we could let these guys talk to people who wouldn’t normally pay any attention to them. But when we played New South Wales, while one of the guys was on stage giving his talk, the police were at his house, beating up his wife.

By contrast, per the account that Shane Maloney and Chris Grosz made in the December 2013/January 2014 issue of The Monthly, Gary Foley was sitting in his home in the Sydney suburb of Redfern one Summer afternoon when ‘some Pommie bloke rings up and says he’s Joe Strummer from the Clash’. Strummer then invited Foley to the band’s hotel to educate him on Australian politics. According to Maloney and Grosz: ‘The pair hit it off immediately, and Strummer ended up asking Foley to share his thoughts on stage during that night’s gig at the Capitol Theatre.’

Lending slightly more support to Simonon’s version of events, Strummer made no attempt to contact any Māori rights activists in order to find out about politics in New Zealand or to give them the same access to the band’s audiences at any of their four gigs (where they also performed ‘Armagideon Times’) so that they could talk about the exploitation and oppression they suffered. Indeed, there was pressure on Strummer and the band from Clash fans – but only to play the South Island. A successful petition led to an extra gig being held in Christchurch at its town hall on 8 February. During the tour, Strummer went busking with his ukulele in Auckland and made no mention of Māori rights in an interview at the city’s train station or at their first gig there.

Whatever the truth of whether Strummer invited Foley or three Aboriginal activists approached Simonon, in late 2002, upon Strummer’s death, Foley recalled: ‘No doubt there were young women who turned up at the shows and were keen to bed him, but he always deflected them from those sorts of thoughts and tried to encourage them to think about local political issues and engage them in broader political questions.’

Long before the term ‘intersectionality’ had popular currency, Foley not only explained the historical roots of the racism and oppression that Aboriginal people are subject to but that the struggle to liberate them must also be a struggle liberate women and the working class. At the final show in Melbourne show on 23 February, his message was enthusiastically received, as a bootleg recording of the gig demonstrates. The New Musical Express (27 March 1982) noted a similar response at one of the Sydney shows.

At the Melbourne gig, for example, Foley stated

[I]f we’re going to build an Australia of the future, where everyone is free, where no one is oppressed, then you are going to have to understand that the struggle against racism, sexism and exploitation is one struggle. Next time the unemployed people march, get out there and march with them. Next time women are marching for their rights, get out there and march with them. And the next time Aboriginal people in this state are marching for their rights, be there with them too!

For Foley and his fellow Aboriginal activists, the opportunity to speak to a new audience was potentially invaluable as they prepared to put Aboriginal rights centre stage through protests at the forthcoming Commonwealth Games in Brisbane. Foley thought that speaking to Clash fans might ‘incite some of these young punks to join in’. Maybe his rousing rhetoric did the trick, as Maloney and Grosz reported: ‘That September, there were so many demonstrators against the Commonwealth Games that Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen declared a state of emergency.’

Among the major studies of The Clash and Joe Strummer and where the Australian tour is covered, Marcus Gray and Chris Salewicz offered only fleeting mentions of it. Consequently, it is useful that two more recent studies, found in edited collections on The Clash, have emerged. Both cast doubt on the size and longevity of the impact of Foley’s foray into the coveted Clash community. One is by Gabriel Solis, a scholar of African American music and of Indigenous musics of the Southwestern Pacific, and the other is by Alessandro Moliterno, a campaigner with Australian Progress. They largely utilised newspaper reporting from the time. Lingering perhaps on some of the most standard interrogations of activism’s very function, they argue that while it was believed to be a worthy initiative, there were definite limitations. Was it a case of just (p)reaching to the converted? Were the numbers attending the shows too small to make a difference? Was the rhetoric of Foley and Strummer simply not enough to turn apathy into alacrity and interest into activism?

Although it seems Solis believed that Foley spoke at more gigs than he actually did, he points out that Foley did not attempt to link the different struggles together at the Brisbane show, preferring to use the framework of black power and black nationalism – a framework he had learnt from the Black Panther Party when some of its members visited Sydney.

Beginning with his declaration of ‘I’m a black Australian’ at this Brisbane show, Foley charged that

Our people have lived in this country for fifty thousand years. And until two hundred years ago when some bloke by the name of Captain Cook came out here. … When you arrived, when white men arrived in this country they either shots the blacks, poisoned their water holes [or] murdered them right, left and centre … and those that were left were rounded up like dogs and cattle and stuck on these places called Aboriginal reserves, which were nothing less than concentration camps.

Using this framework may have seemed to be a case of pushing away potential support, especially in the most racist of states within Australia at the time. Ironically, Solis argued that this more confrontational approach may have been used because the punk scene in Brisbane relatively more advanced and, thus, he thought more receptive to this message of The Clash than in any of the other major Australian conurbations. It was also he thought because Brisbane was the only city to see the emergence of the Black Panther Party of Australia. Nonetheless, Solis emphasises that Australian punk bands did not readily embrace the agenda of Aboriginal rights, nor Aboriginal people punk. In an age before the rise of the internet and social media, this may not have been helped, he reasoned, by the underreporting of the tour itself in the Australian media. By contrast, Moliterno argued that there was something of a media blackout – not so much of the shows themselves, but of Foley’s speeches. The most extensive coverage of this aspect of the gigs was provided back in Britain, albeit a few weeks later, by the New Musical Express of 27 March 1982, and found limited distribution in Australia.

What identifiable – qualitative and quantitative – imprint remained once the Clash left for shows on other foreign shores in south east Asia? By this measure, we might argue that the initiative proved to be relatively disappointing and dispiriting, but success in challenging prejudice and raising awareness cannot always be directly and easily measured. Besides, Foley’s efforts have to be seen as part of his lifetime’s work and a much bigger project he shared with Aboriginal rights’ activists. Nonetheless, what lessons can be learnt?

Firstly, it should not be concluded that music – especially the live, visceral and febrile gig – does not matter for advancing progressive political purposes, nor that black and white unity in action is not possible or meaningful through such a medium. Publicly planting your progressive flag in the ground is a first step for any possible subsequent action, and showing support to a cause or campaign helps establish its wider public legitimacy as well as providing sustenance for its activists.

Secondly, we are reminded the scale of the activities and the scale of the aims should be aligned. While the tour was more than an ordinary, one-off benefit gig, it would be unrealistic to expect a significant advance in the fight for Aboriginal rights just because the Clash – even at their height of worldwide fame – lent their support to it for two weeks. If music is to play a big role or have a truly great impact, it needs to be on something like the scale of the Rock against Racism movement of 1976-1982, which saw numerous gigs organised up and down the length of Britain. The singular high-point of this successful struggle against the Nazi National Front was a performance in London by the Clash alongside reggae band Steel Pulse in front of 100,000 people in April 1978, at the conclusion of a march. The likes of Billy Bragg and many future senior left and union activists attended this event and testified to how it convinced them not only to become active anti-racists and anti-fascists, but also socialists.

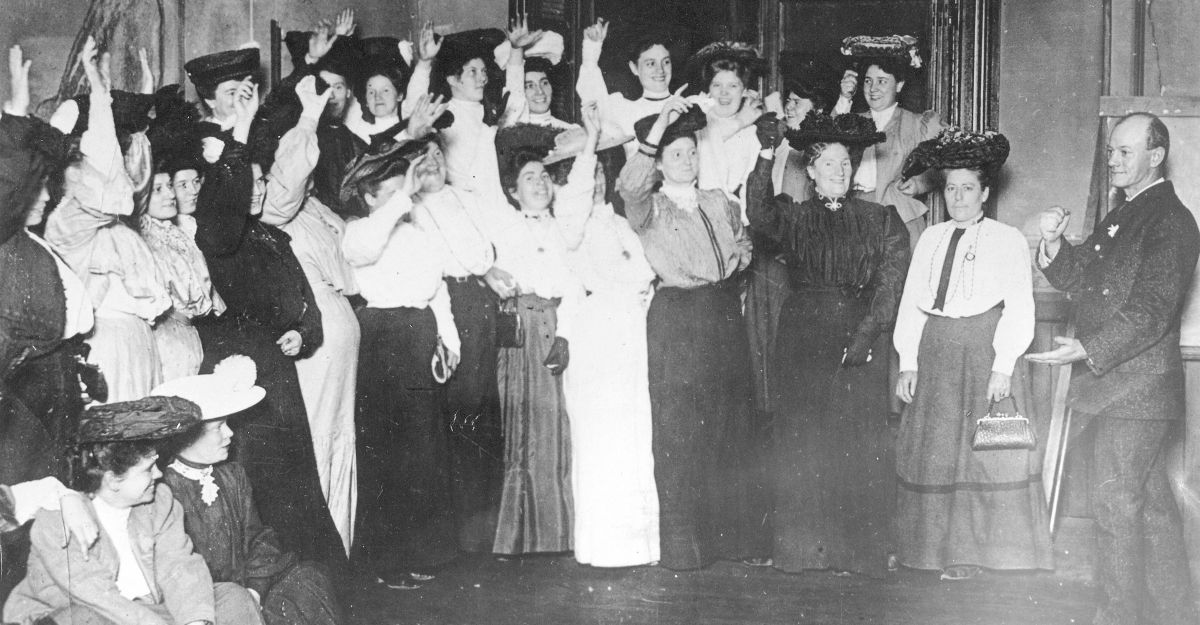

Image: The Koori History Website