Over the past six weeks, as Aotearoa faced the threat of COVID-19, communities and individuals around the country responded in a myriad of ways. Early stages saw panic buying whereas some thought the whole thing was a bit of a joke, laughing at those in face masks, and laughing even more at any suggestion they should cancel their holidays. Others still were irritated at the intrusion into their plans and insisted they had a right to continue their daily affairs. My own East Coast community and many others responded early with direct action to stem non-necessary travel by reminding people directly of the alert level laws as they entered our region.

In the past two weeks, political forces and some factions of the media have branded our action as ‘unlawful roadblocks’ by ‘vigilante groups’. Like so many cases, attacks are founded on fear, which is, in turn, rooted in ignorance, and so to understand our motivations, you must first understand our history.

As strongly as the term ‘unprecedented times’ has featured in recent weeks, facing deadly epidemics is hardly unprecedented for Māori or our nation. Waves of epidemics decimated Māori from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s. Most of these were either introduced by early explorers or through imported animals, or originated as a result of unsanitary colonial settlements. Low immunity to introduced diseases left Māori at highest risk, and the consequences were grave: from first European contact to 1840, Māori lost an estimated 30 per cent of our entire population, mostly to epidemics. A further 30 per cent were lost in the twenty years that followed. The influenza epidemic of 1854 killed over 5000 Māori. Further epidemics continued to batter us through the 1800s and into the 1900s.

There are stories of the death rates for small communities being so high, that eventually they could not contain them in the urupā (burial ground), resulting in mass graves. In many urupā around the country today, you can still see the graves of children and their young parents – rows of them, still cared for, still remembered.

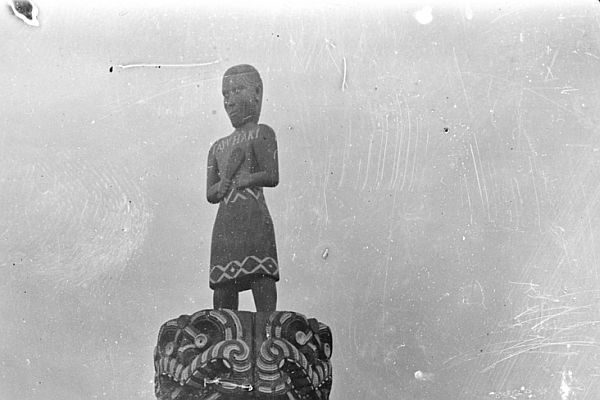

You see, we don’t forget our dead. We hang their photos in our meeting houses, and we sleep beneath these photos of young babies, in christening gowns, who never made it to adulthood. The young mothers and fathers who passed away before becoming elders. We immortalise their stories in carved pou on our marae so that we speak of their experiences when we gather. We keep our ancestors close, their memories live on with us, and their lives become our lessons.

Pou whakamaumahara (memorial) at Te Kōura marae, Maniapoto, in memory of those who died in the 1918 influenza pandemic, carved by Tene Waitere of Ngāti Tarāwhai. A similar pou was carved for Te Ihingarangi marae, Waimiha. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

Pou whakamaumahara (memorial) at Te Kōura marae, Maniapoto, in memory of those who died in the 1918 influenza pandemic, carved by Tene Waitere of Ngāti Tarāwhai. A similar pou was carved for Te Ihingarangi marae, Waimiha. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

Nor are our responses without precedent. When the first wave of the global epidemic of 1918–1920 came through, Māori were again hit hardest, losing nearly 5 per cent of an already decimated population – one of the highest influenza death rates in the world. In addition to low immunity, political bickering and a fear of economic disruption led to state inaction, the price for which were thousands of Māori lives. When the second influenza wave came, small townships took action. In the Coromandel, checkpoints were set up at all roads coming into the district, and temperatures were taken. In Te Araroa, my own ancestors also manned the entry points to control traffic coming through. Consequently, Coromandel and Te Araroa were two of the very few townships around the country that escaped the ravages of the second wave.

When you consider how closely Māori hold our ancestors, our reverence for history, and the scale of the loss we have suffered from epidemics, it is easy to understand the unease Māori communities felt when COVID-19 arrived on our shores. When you further consider that not only has the state historically failed to protect our ancestors, but that the common Indigenous experience of colonisation includes the use of disease as a genocidal weapon, then you can understand why we could not wait for anyone to come and save us.

When we heard that the COVID-19 risk factors were illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, heart disease and chronic respiratory illnesses, we already knew that this related to nearly our entire population. Research and reports aside, we know this because we live the reality every day. We are the ones burying our loved ones from chronic illness year after year. We are the ones struggling to navigate a health system that was never built with us in mind. We didn’t need a statistician to paint a picture for us. We already knew, in our bones, what COVID-19 meant for our families. In a horrific and potent reminder of our history, Pacific people in Los Angeles are dying twelve times faster than white people from coronavirus, for exactly the same underlying factors of chronic illness listed above. If you have ever looked to the face of your elders, people that you have looked up to for strength and guidance since childhood, and seen genuine fear for their lives, then you will understand that being a protector is not really a choice: it is a duty that was carried and defined by our ancestors well before we came along. It is framed by the knowing, from our own lived experience, that nobody will come to do this for us, and nor could they do it as effectively as us, for nobody knows and loves our people and place as we do.

The Māori duty to protect has served both Māori and non-Māori people of this nation multiple times throughout history. It led to thousands offering their lives during both world wars, in service to the Crown and nation. It led to Māori households taking in and feeding non-Māori during the Great Depression. It led Māori gang affiliates to offer their direct protection for Muslim families to pray safely after the Christchurch massacre. It led to marae opening their doors to the entire community in the aftermath of the Christchurch Earthquake. Indeed, most marae also serve as civil defence centres for communities across the country. The Māori duty to protect runs deep, and has risen to the benefit of Aotearoa time and time again.

Keeping our communities safe from Covid-19 has not been easy work. Our people have worked through the day and the night, through sun, rain, and 4 am hailstorms to protect our community members, Māori and non-Māori alike. We have diligently monitored and reported back on our data to our communities, councils and Crown, and used that data to forge grounded, relevant solutions. We have faced off against meth dealers and belligerent breachers who refuse to have their activities curtailed. We have been faced with the heartbreak of whanau who have lost a loved one and not been able to grieve or farewell them as we usually do. We have seen distressed parents desperate to get to their children and brutalised partners escaping their abusers. In all of these instances, we have called upon police, health or social services to provide support for those in need. Lockdowns and traffic monitoring are not, as it turns out, as simple as they sound.

From the outset, we have extended our hand to Crown agencies to work alongside us in the protection of our communities. We have always wanted the advice and support of experts to carry out our duties in the safest way possible. Like all relationships with the Crown, it has not been without challenges, and it is still a work in progress, but in supporting our protection of our communities, New Zealand Police have stepped into their partnership responsibilities in their fullest sense.

This has, of course, become a low-hanging fruit for right-wing politicians and media commentators to stoke the fires of racism, decrying any kind of roadside community service as unlawful vigilantism, even when done with the support and presence of police, council and health services. National Party leader Simon Bridges has said: ‘There is no scenario, and it is Law School 101, where a member of the community is acting lawfully by stopping another Kiwi on a road in New Zealand’.

Let’s be clear: Simon Bridges has never spoken up against traffic management in front of schools. He has never complained about community traffic management for the Tauranga Triathlon. He has never decried community traffic management for farmers’ markets as unlawful vigilantism. He is choosing this context because it is an easy target for a bully, desperate to remain relevant in the face of a powerfully popular government. It is a cruel, boring and sad reality that attacking Māori has become the default campaign tactic of the right every electoral year, but this year, with such immediate life or death consequences, the heartless right-wing of New Zealand politics and media have proven that, even in the face of extreme adversity, they are simply unable to rise above the lowest form of themselves.

Conversely, the actions of Iwi and hapū have shown that in leading out these protective direct actions for the communities under our care, we can take from the precedents set by our ancestors over time, and apply them in a way that protects both Māori and non-Māori. We will not stand aside and again become a global statistic. Our duty to protect has served the nation multiple times, through war, disease, economic depression and natural disasters. The only thing that seeks to stand in the way of us continuing to serve and protect our communities in this way is racism, and we cannot let it win.

Consider joning the petition in support of community checkpoints.