Withing ten minutes of watching the first episode of the Netflix documentary series Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem and Madness, I texted a like-minded friend to ask if he knew of it. ‘You must watch this,’ I wrote. He responded almost immediately: ‘we just started now and I AM IN’. Our incredulous text conversation continued on and off for days.

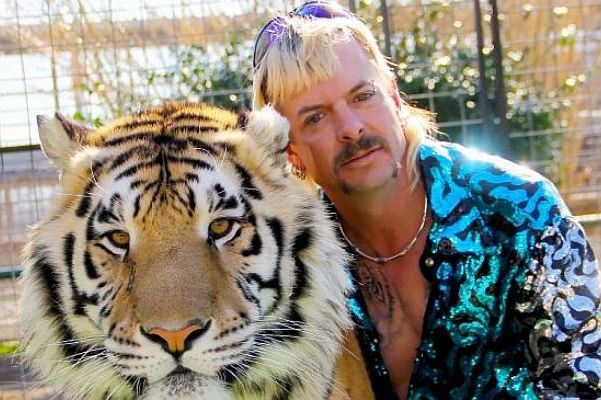

A Netflix-subscriber-wide glee (or horror, or obsession or any number of complex emotional responses combined) quickly made the seven (or eight) part true-crime series about American ‘big cat’ zoo owners the streaming service’s most popular show in several countries. Tiger King centres around the bizarre Joe Exotic and his inept murder-for-hire plotting against fellow Panthera enthusiast Carole Baskin, with a Greek chorus of lengthy interviews with astonishing supporting characters from this subculture. Exacerbated by the enforced homebodiness of a global pandemic, the online discussion, meme-making and thinkpiece-reading has been, to many, a welcome distraction. My husband and I took two hours to watch the first episode because we had to pause every few minutes and react to what we had just seen. ‘There’s so much to unpack every moment that it’s like reading James Joyce,’ he observed.

If this tells you anything – apart from how annoying it would be to watch TV with the two of us – it’s that Tiger King operates on two pop-cultural levels. The micro: we gaze astonished and delighted at a glamour shot of three meth-addicted married men printed on a microfleece blanket; and the macro, in which the show emerges as a perfect synthesis of several different mass media genres stretching back over the last century.

Here’s a truism from introductory sociology: people like to create in-groups and out-groups, and the obverse of solidarity is ‘othering’. In popular cultural contexts, this can mean pointing at things or people ‘we’ consider strange, humorous or thrilling. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, people gathered in large groups at fun fairs or circuses to look at physically unusual people or animals. The development of mass media meant that we could do this one step removed: we no longer needed to look into the eyes of the subject that is being exploited.

Yet it’s too pat to assume that the screen merely distances us from ‘weirdos’, allowing us to other them more neatly and completely. Films like Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) or the Maysles brothers’ Grey Gardens (1975) walk an uneasy tightrope, inspiring shock, empathy, laughter, identification and amazement all at once.

Where is the line between a fascinating subject and the exploitation of the Other drawn? In Tiger King, Joe Exotic – a megalomaniacal polyamorous southern gay tiger-zoo owner with a penchant for magic shows, drugs, guns, criminality and feeding his pizza restaurant customers expired Walmart meat – combines so many layers of othering as to become an irresistible subject for practically any audience.

Joe is also obviously obsessed with being famous. He spent years filming almost everything that happened in his Oklahoma animal park; he regularly created music videos and broadcast internet television shows about his animals, his life, and his intense hatred of Carole Baskin, owner of Florida park Big Cat Rescue. In creating these texts, he falls squarely within the milieu two late-twentieth century media inventions much-derided by people who have never tried watching them: of talk shows and reality television.

One of Tiger King’s most garrulous interview subjects is a man who spent some time trying to make a show from footage he’d taken in the big cat park. This reminds us that talk and reality shows are only ‘unscripted’ to the extent that their subjects ad-lib their reactions: as anyone who spent any time watching Jerry Springer or Maury Povich knows, at some point a cheating spouse will be remonstrated with on stage, or a man will dance mean-spiritedly when a DNA test informs him he is ‘NOT the father’. Reality shows have even more explicit plots, manipulating footage to create stories or drama out of the most minor of conflicts, or filming (fashion, travel, cooking, drag, love) competitions between variously skilled contestants.

Going on television to achieve your life’s ambitions runs the gamut between foolish and strategic. No one could say that having a wedding cake flung at you on stage is going to solve your marital problems, but winning Top Chef is certainly a way to improve your career prospects. At this point, it’s hard to decide whether Joe Exotic has won the PR battle against his own frankly awful actions, but he certainly has given it the college try.

Tiger King differs from reality TV, however: it gives us the Other cloaked in the high-end documentary dress of an Errol Morris or a Werner Herzog. The production values for this, and for other recent documentaries of the ‘disturbing’ variety such as Wild Wild Country or Leaving Neverland, speak to us of seriousness, of significant subject matter: lengthy drone shots, conceptual soundtracks in the style of Philip Glass, gorgeously framed interview subjects. What jars (and delights?) us in the case of Tiger King is that the high-cinema style framing is used for a jet ski montage. It’s like Kenny Powers refracted through Ken Burns.

We’ve known for decades that ‘high culture’ and ‘low culture’ are an increasingly false dichotomy, the bleeding edges of each mingling together to such an extent that it’s hard to tell which is meant to be which. In Tiger King, the waters are so muddied that it’s impossible to work out if there is an auteur involved. Have the filmmakers managed to bend the world of Joe Exotic to their own vision? There is an argument to be made that, in dressing up this sordid tale, they have exploited his milieu for classist laughs, just as Joe exploited his own tigers and amputee workers for money and power. But the increased mainstreaming of weirdness in documentaries shows exactly how much value we put strangeness and surprise, and if anyone knows that, it’s the self-mythologising Joe Exotic. The big cats may not wind up having the last laugh, but he probably will.