In Melbourne last month, a near-empty courtroom running on coronavirus protocols featured large screens on which barristers read for hours from complex pieces of legislation. Two hundred kilometres away, in Western Victoria, a group of Indigenous people and their supporters sat near their ever-burning campfires under 800-year-old sacred trees, not saying much at all.

There couldn’t be two scenes more alien to each other, yet so intimately entwined.

The case in the Victorian Supreme Court was a challenge to the determination of the Victorian Roads Corporation (formerly VicRoads) to push a highway upgrade through fields and forests to the east of Ararat. The proposed route cut through the traditional lands of the Djab Wurrung people, and a group of Djab Wurrung and others have been camped there for nearly two years at an embassy and a few other key sites, occasionally clashing with road workers and police.

However, this court case didn’t involve the Djab Wurrung: it was brought by two landowners from the same family whose land was compulsorily acquired for the highway, along with a community action group known as KORS who have opposed the route of the highway for nearly ten years.

The three-day case, was argued – as cases involving government decisions often are – on highly technical grounds: why was that route chosen for the road? How was the decision made? Exactly who made it? Could the court even legally rule on it?

At the same time, the issues were startling in their simplicity: everyone agreed that a count of trees made for an environmental effects statement before the road route was chosen had been wildly inaccurate. It stated there were 221 ‘large old trees’ along the route; that number was in fact closer to 1500. There were also mistakes made in relation to the habitats of the threatened striped legless lizard and the critically endangered golden sun moth, both of which exist along the road route. VicRoads had known about the miscount for somewhere between eleven and eighteen months before notifying the landowners and the general public, respectively.

The landowners and KORS wanted the whole route decision nullified and reconsidered. Landowner and plaintiff in the Supreme Court case MairiAnne Mackenzie described the proposed road as a massive barrier through the landscape. ‘Strangling the land by adding new barriers to it guarantees that saving a few jewels in National Parks won’t be enough,’ she said. ‘If people aren’t interested to look after their own environment, there’s not much hope.’

The Roads Corporation and the State Government claimed in court that the tree miscount didn’t make much of a difference in the choice of road route, or, even if it did, that the court didn’t have legal grounds to change the decision. Unsurprisingly, the court’s decision will take some time to make.

To the traditional owners of the land, the matter is moot. Their understanding of their country comes from a framework not so much scientific as cultural and holistic, drawing on thousands of years of coexistence.

Speaking before the case was heard, protest leader Zellanach, or ‘D.T.’, Djab Mara, described how he felt about the future of Djab Wurrung land being decided in a Melbourne courtroom: ‘I feel sick. Physically feel sick. Because detachment is making the rule of law on a land that they’ve never been attached to.’

The protestors at the embassy talk about following the ‘lore’ of the land which, Djab Mara says, ‘really is mother earth’s law, which is the law of Djab Wurrung.’

We take the law of the land, we take the law from the land, so we take everything that’s involved with the land into account.

But when we talk about, I guess, L-A-W, Westminster law, that’s really man-made law, really it comes from Church of England law, so it’s made up … whereas our lore of the land never changes.

The judges are all making decisions based on the rule of law … man-made law. Our lore comes from creation. It makes me physically sick because it’s not even about law, it’s about strategy in the court of law. It’s all strategy.

That legal strategy, for better or worse, is probably the only reason the highway extension hasn’t gone ahead yet. While the protestors are fiercely determined and have been able to draw on a wide network of supporters and allies, the court cases have been instrumental in preventing the road from being built – so far.

In September 2019, a pending Federal Court case, combined with a swarm of protestors on site, helped force a deal. The State Government temporarily agreed not to proceed on a large part of the works, in exchange for being permitted to build a smaller section (about 3.8 kilometres) that did not cut through the most sensitive areas. That section of road is now well advanced, but the future for the rest of the route is unclear.

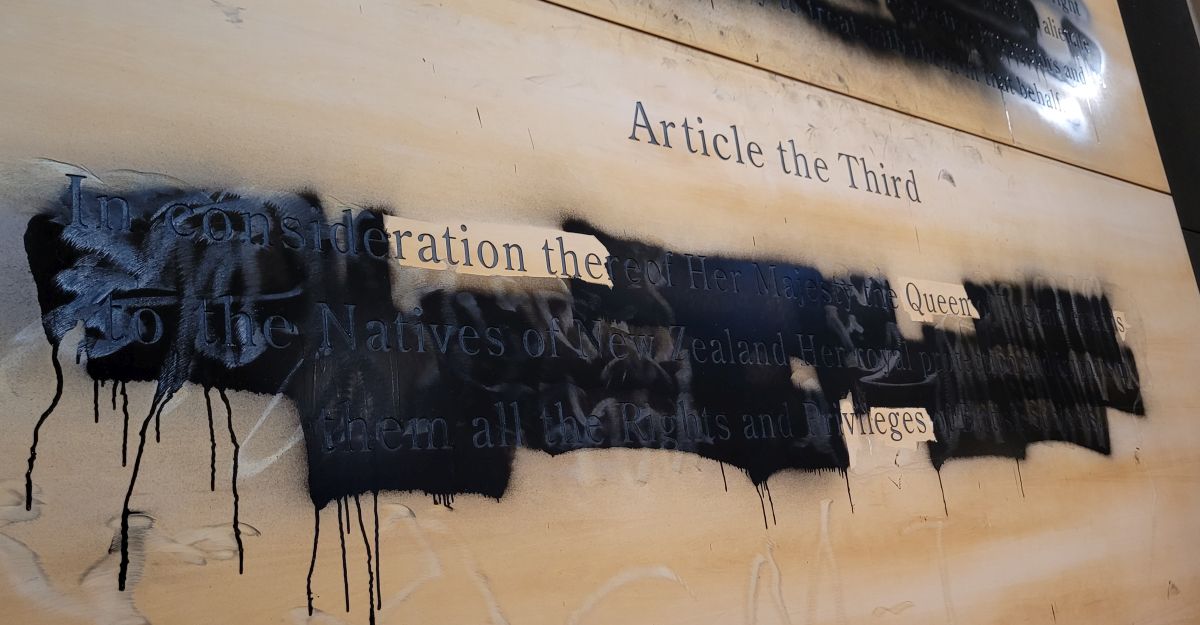

Unlike the present case, which only looks at environmental matters, the Federal Court case was brought by Djab Wurrung people, including elder Aunty Sandra Onus, and was based on the significance of the land to Indigenous people. When it was heard, back in November, the court ruled that Indigenous heritage matters had not been properly considered and sent the matter back to the Federal Minister for the Environment for a new decision – the second time the court had done so. The minister’s decision is still pending: it will cover the importance of the sacred trees – some of which are birthing trees, some of which bear pre-colonisation axe marks, and others which are claimed to be mortuary trees – as well as the significance of the landscape itself and the dreamings it contains. It’s possible, however, for the minister to agree that yes, all these things are important, but still say that the interests of the nation, in the form of faster travel times and claimed safety improvements, override heritage.

That case, this most recent Supreme Court case and numerous other small legal challenges and queries have been largely run by a tenacious lawyer named Michael Kennedy with a handful of pro bono barristers and others, working with the landowners and Djab Wurrung people who oppose the road. (There is another group called Eastern Maar, the Registered Aboriginal Corporation for the area, which no longer opposes it.)

While Kennedy and Zellanach Djab Mara don’t always see eye to eye, they have a common goal: to save the trees and the landscape around them. The mechanism for that could be Indigenous heritage; it could be the environmental issues; or it could be the moral authority that accrues from simply sitting, day after day, year after year, on a piece of country as your ancestors did – much as the Gurundji people did during the 1966 Wave Hill Station walk-off.

Last year, Djab Mara put it this way: ‘We have to be in the faces of these people because otherwise – silence is acquiescence. So I’m going to be in your face every single day, you people are going to know about me every single day. You’re going to be educated every single day. We’re not going away, we haven’t gone away in 250 years, you tried to wipe us away, we come back generation after generation, yeah?’

The most recent case was heard on the first three days of the Supreme Court’s move to ‘e-justice’ because of COVID-19. The judge still sat on the bench, but the barristers appeared on video links with dodgy audio that sometimes dropped out; submissions were made in writing instead of argued in court, and there were numerous small technical glitches that the court bore with patience and the exaggerated formality of the law.

Meanwhile, up on Djab Wurrung country, the protest camps prepared for what may be a long winter, and they adapted to COVID-19, too. They issued guidelines for visitors – don’t touch what you don’t need to, maintain social distance, wash your hands, bring your own utensils and cups – and asked supporters to do what they could remotely instead of visiting.

And they kept on waiting.