Anyone of a leftist disposition who spends long enough on the internet will sooner or later encounter the online figure that has come to be known as logicbro. There he is (for he’s almost always a he), accusing you of being ‘factually incorrect’, urging you to ‘get your facts straight’, and asserting that you are ‘emotionally driven and therefore prone to making sloppy mistakes’. He resides in the online right’s favourite haunts – reddit, 4chan, and the rest – but considers himself above politics. He takes special pleasure in deploying cold, hard rationality to ‘destroy’ his interlocutors.

Having taken introductory critical reasoning classes, bookmarked the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, and listened to the podcasts of Sam Harris, the logicbro feels equipped to dismantle the arguments of his preferred adversary, the Social Justice Warrior or SJW, whose logical fallacies, ‘intellectual dishonesty’ (a beloved phrase) and progressive biases he tirelessly decries. Brought up on the rhetoric of the New Atheists, the logicbro has embraced as his philosopher-king Ben Shapiro, the American commentator whose catchphrase ‘facts don’t care about your feelings’ – conveniently scaled for coffee mug and t-shirt alike – has become his mantra. His signature move, cribbed from the New Atheists’ playbook, is to say: ‘If your political agenda is incompatible with the facts I am merely describing, then that is your problem.’

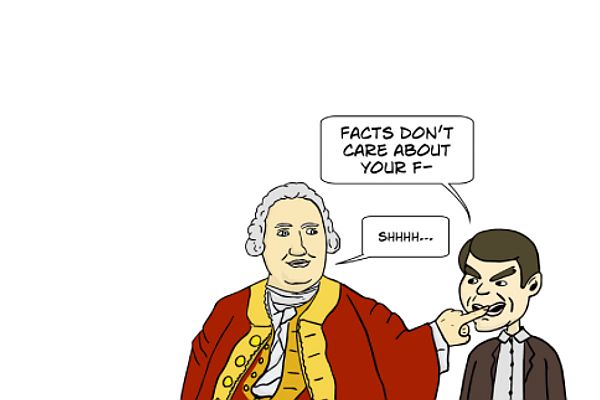

Shapiro appears in a meme-ish cartoon by Ryan Lake on the cover of Ben Burgis’ new book Give Them an Argument: Logic for the Left, the latest release by the always interesting radical publisher Zer0 Books. However, the book isn’t a Chapo Trap House-ish takedown of the logicbro. Rather, Burgis – a Rutgers University philosophy professor who wrote his doctoral dissertation on logical paradoxes –makes the case for the reclamation of reason by a Left that has become increasingly spooked by its (mis)uses. And no wonder.

The pronouncements of ‘rationalist’ New Atheist luminaries like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris – who once might have stood as defenders of the logic and reason seemingly abandoned in the white heat of the September 11 attacks – have long-since curdled into toxic sophistry. On what rational basis can the Muslim call to prayer be said to be ‘aggressive-sounding’ (per Dawkins)? Do every ten thousand Muslims who migrate into a Western country really harbor twenty Islamist terrorists (per Harris)? Not to mention the fact that the entirely illogical case for war against Iraq was stridently backed by another leading New Atheist, Christopher Hitchens.

It is, I think, no accident that the rise of New Atheism during the mid-2000s coincided with the founding of the platforms where its valorisation of ‘reason’ would be most perniciously taken up. 4chan appeared in 2003, reddit and YouTube in 2005, and it was here that the ridiculing of the bad ideas of the religious became both a parlour game and a badge of intellectual gravity for a particular kind of rightwing blowhard. As the YouTuber ContraPoints, a progressive transwoman, has argued:

What’s alarming to me is the way certain people on YouTube flex whatever intellects they have by attacking the most facile and ignorant arguments of religious fundamentalists and conspiracy theorists – arguments which any clever middle-school graduate could debunk – and then they emerge from this easy triumph filled with confidence that they’re fully equipped to tackle extremely complicated social and political issues without first doing any serious research.

It is no surprise that the online weaponisation of reason – a trait historically portrayed as male-gendered – should have filtered down from the New Atheist boys’ club to the internet’s most misogynistic corners (even if, in an interesting twist, the phenomenon is today being spearheaded by Shapiro, an observant Orthodox Jew, and Jordan Peterson, who appears to be some sort of Christian). In her discussion of the ‘masculinisation of reason’, feminist philosopher Herta Nagl-Docekal writes:

The traditional image of gender difference characteristic of Western culture ascribes reason to men and emotion to women. We see this expressed in the way abstract thought, objective judgment, and an orientation to general principles are seen as masculine character traits, while subjectivity, spontaneity, and an orientation to the concrete and particular are seen as typically feminine character traits. What this means for women, among other things, is that their faculty of reason is questioned—as witnessed by the familiar jokes about ‘women’s logic’.

In Give Them an Argument, Burgis explains why this gendered yoking together of reason with a lack of emotion, and irrationality with a surfeit of feeling, has left many progressives distrustful of logic as a persuasive strategy:

… both free market libertarians and creepy online ethnonationalists delight in contrasting their investment in ‘facts’ and ‘logic’ with the left’s alleged obsession with emotions. Many leftists quite correctly sense that the point of this rhetorical strategy is to turn a disturbing lack of empathy with the victims of rightwing policies into a virtue. Once you’ve been told enough times that you wouldn’t object to human rights violations in Palestine or on America’s southern border if you were less ‘emotional’ and hence more ‘logical’, it’s only natural to start to wonder whether there’s something very wrong with anyone who makes a big deal of valorising logic.

And yet, as Burgis asks, where does the ceding of this intellectual territory to an increasingly regressive online right leave progressives?

In the first instance, I would argue, it leaves them ill-equipped to make even the most basic of critiques based on the principles of logic. When, to take one notorious example, Jordan Peterson invokes the dominance hierarchy of lobsters to justify the unequal distribution of power between men and women in human societies, it is far from flippant to point out the fallacy that underlies such thinking (Burgis provides a handy list of others at the back of his book although, as he writes, it is not always necessary to know, on a formal level, why an argument you’ve just heard is a bad one).

More fundamentally, though, as Olivier Jutel has argued in this journal, the disinclination of progressives to engage in rigorous debate risks fostering a politics ‘that does not expand the quality of left thought so much as garner converts to a woke clergy’. (A veteran member of an Australian socialist organisation once told me of the time a young activist, corrected on some minor point of fact, earnestly accused them of ‘oppressing me with your knowledge’.) However damaging the same-sex marriage postal vote was, becoming an unnecessary referendum on the dignity of queer people just as its detractors knew it would, calls for a boycott – which surely, had they been more broadly taken up, would have backfired – were wrongheaded. as Dennis Altman wrote at the time, ‘we don’t always get to choose our battle grounds’. Similarly, it struck me that the signalling by progressives of their support for marriage equality within their own social circles was a strategy doomed mainly to rehearse a familiar Left-ethical position. Better to make the case for same-sex marriage’s lesser known social and economic boons, and better still for the benefit of those least likely to already support the cause.

This is not to argue that certain fundamental rights ought to be up for debate, or that the willingness of progressives to enter into such arguments is a political strategy worth pursuing. An enormous amount of time and energy has been wasted ‘debating’ the facts of climate change long after the science was established, not to mention shown to have been systematically distorted and concealed by fossil fuel interests (the false equivalence fallacy, whereby opposing positions appear to be logically alike when in fact they are not, isn’t one that Burgis addresses but that we should nevertheless be vigilant of). And it is, no doubt, galling for progressives, and especially those who identify as female, non-white, non-middle class, and so on, for the Left to have to constantly perform the emotional labour of telling the rest of the world why this or that shit is not okay.

But nor should we fool ourselves into believing that assertion without argument is capable of doing the same work as persuading on behalf of the goals that we care about. As the presidency of Donald Trump and any number of other recent shocks to the global body politic have shown, there is little comfort to be taken in the view that the moral rightness of the Left is self-evident, or its path to legislative reification certain or irreversible. The problem with the logicbro is not his claim to solid reasoning, but rather his use of its semblance to game his opponents and, ultimately, shut down debate for the Left – an irony lost on the libertarian right that commentators like Shapiro represent. But moral opprobrium in itself, whether directed at the insufficiently woke within our own communities, or the creeps, bullies, and fascists of the online Right, is not enough. If building a more just world really is our aim, then, at some point, we have to give them an argument.

Image: A detail from the cover of Give Them an Argument