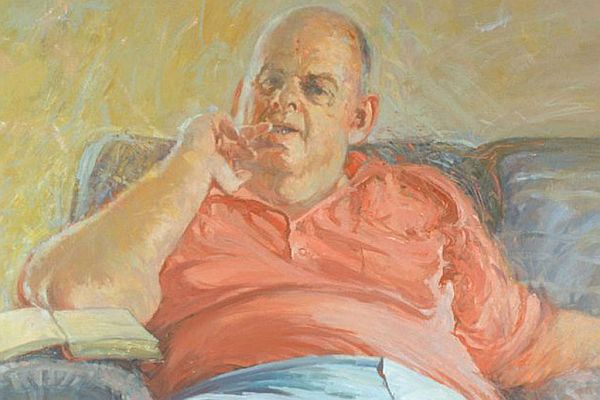

When monuments fall, they create ripples, shockwaves, fragments, pyroclastic flow – pick your metaphor. Les Murray was definitely that. Over his long career, he produced more poetry, more critically well-regarded poetry, and – stranger still – more commercially profitable poetry than pretty much anyone else in the Australian landscape. Unlike the famous expatriate coterie of his peers (Peter Porter, Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes, Clive James and so forth), he did it mostly from his own paddock, without modulating his principles to fashion or his prejudices to progress. You could think of Murray as the problematic old bastard grandad some of us had, if he’d been an internationally renowned poet. Structurally rarer, Murray’s work created and sustained an entire idea or moment or myth of Australia pretty much on its own. Let’s be blunt, there just aren’t that many writers who can pull off a feat of that magnitude.

Setting out to write this, I’m attempting to navigate a fair few pitfalls and some possibly irreconcilable priorities, and politics. I’m a poet working in European poetic traditions. A lot of us try to escape or elide that in a number of ways, but settler Australian poetry is European poetry written in and about the Australian continent, it always has been and it continues to be. Forms are not neutral, and these versions of poetry have philosophical and political lineages, and loyalties that are antithetical to – and hostile towards – other ways of thinking and writing, particularly towards the poetries that have been here a hell of a lot longer than we have. This isn’t virtue-signalling, whatever the hell that actually means. Take any prominent definition of the term you like, for instance Roman Jakobson’s

Poeticity is present when the word is felt as a word and not a mere representation of the object being named or an outburst of emotion, when words and their composition, their meaning, their external and inner form acquire a weight and value of their own instead of referring indifferently to reality. (378)

and you’ll find it riddled with binary logics that don’t have any substance in Aboriginal poetics and cosmology. It shouldn’t need stating, but just taking a different poetics and trying it on like Lawrence of Arabia’s keffiyeh, or a possum-cloak, and stitching it to some of the more mythopoeic moments of Greek myth or Judaeo-Christian theology, is also a deeply shit idea.

In the Australian context, this was most famously attempted by the Jindyworobak movement of the 30s and 40s, which was mostly centred around Rex Ingamells. The name comes from the Woirurrung language from around Melbourne. It means to ‘join’, or ‘annex’ – as in Poland, 1939. Not inconsequentially, they found it in a 1929 book by James Devaney called The Vanished Tribes.

Murray was proud to call himself the last of the Jindyworobaks, a problem I’ll discuss in substance below. For now, I want to emphasise the closure, the antinomy that continues to structure settler writing in Australia, in which any simple assumption of formal cadence implies and reifies colonial possession. As far as I can see, this is the deep grammar of settler writing. There is no direct or simple egress from this predicament, and anything that looks like it is selling you something that belongs to someone else. As Derrida has it:

There is no sense in doing without the concepts of metaphysics in order to shake metaphysics. We have no language – no syntax and no lexicon –which is foreign to this history; we can pronounce not a single destructive proposition which has not already had to slip into the form, the logic, and the implicit postulations of precisely what it seeks to contest.

This isn’t a tangent, or a theoretical cufflink-flash. It’s one of the central problems of Australian Poetry™ and one of the salient issues with approaching Murray’s work.

I write from many of the same traditions that informed his poetry, and in a technical, aesthetic sense, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t think that some of it’s very good, and occasionally even brilliant. But I’m also writing as a Marxist with deep commitments to the possibility of a decolonial future for this country, in which Aboriginal land rights, culture, poetry, and philosophy are honoured as the vital forces they are, and it’s equally true that Murray went out of his way to elaborately fuck over exactly these kinds of progress.

So, a discursive tangle. Unlike a lot of people in the scene, I never met Murray, so I’m even less interested than I would otherwise be in writing the kind of roseate well-fuck-it-he’s-dead-here’s-a-nice-poem kind of eulogy that’s doing the rounds – though I note some of them are admirably balanced and incisive. But to be honest, I’m also uninspired by the idea of a conventional paint-by-numbers leftist critique of his politics. It’s too easy, and he was too complex and too influential a figure to dismiss so simply. So, in terms of critical praxis, this is going to be eclectic to say the least. Borrowing one of Murray’s metaphors, I think I’ve demonstrated I can swing an axe, but strong poetry often knows more than strong poets – Murray said that somewhere, and so have a lot of other people – so hopefully Murray’s working forest can live and breathe and echo with other voices and other politics. The politics, of course, is the big fucking problem.

***

There have been substantial arguments between aesthetics, politics and ethics since at least Plato and Aristotle, and they’re probably not going anywhere quicker than the earth’s biodiversity. On the one hand, we obviously can’t separate the art from the artist or the artist’s politics. On the other, as Barthes demonstrated, the author is dead even when they’re alive, and their work is transposed, reinterpreted and repurposed in myriad acts of reading far beyond their original contexts or politics. On the third hand of this rapidly mutating argument, it’s naive to think that morally indefensible art can’t be compelling or beautiful. The more important pragmatic question, I think, is who’s in the room to make these fine distinctions, and who is pushed or driven out of that room by content or ideology.

In his celebratory review of Murray’s most recent – of many – Collected Poems, Geoff Page argues in The Sydney Review of Books that Murray’s politics were ‘idiosyncratic’ and shouldn’t be simplistically labelled or dismissed. In a brilliantly thorny review of the same book for The Monthly, Nam Le agrees and so – sort-of-to-a-limited-uncomfortable-extent – do I. Sometimes poetry should make you uncomfortable. But when I, and Geoff and Nam enter into this kind of discursive contract, we’re conceding to terms not all that different from the (mostly male) 60s and 70s destructive mythologies of libertarian artistry that Murray despised so much. And felt himself so much above.

Bluntly, I’m conscious of all those other, different, writers to which we never grant the same kinds of special pleading. Certainly not in the pages of Quadrant, anyway. And at the reading end, who is afforded the time, or the care, or the thought, or the labour to appreciate or learn from the formal innovations of a work where the content demands so much of different kinds of reader? Some of the lazier equations between reading and emotional labour that get made are frankly just stupid. But writing as an educator in AusLit, how do we approach most of Murray’s landscape poetry, let alone something like ‘The Conquest’ (1972), knowing that even the most nuanced interpretation can’t palliate a text that legitimates – or sometimes even celebrates – genocide and dispossession? This last point is probably the one that’s gonna stick. I’m going to try to think through some of these problems, looking at some of his most celebrated and some his most criticised poems, within and without their historical contexts. Given Murray’s bone-deep commitment to his own frontier brand of individualism, I doubt he’d mind too much, and in the event that I end up pissing-off Everybody instead of just Half Of Everybody, he’d be positively delighted.

As the plethora of eulogies published by mainstream sources in the last week demonstrates, in the late twentieth-century Murray was probably the one living Australian poet most people here or abroad associated with Australia and/or Australian poetry. Unofficial poet laureate writes ΠΟ with a handful of salt. The personal tributes I’ve seen from a wide range of people who knew him indicate that he was also often kind and generous, particularly to younger and/or emerging writers. But, straight-up, he was also a rigidly narrowminded ideologue who universalised his own experiences of class, grief, sexuality, and mental illness into an effectively militant metaphysical and political narrative.

Murray’s childhood was awful by most (white) standards, his grandfather was a mean son of a bitch, and his mother died of pregnancy-related complications at the age of thirty-five, when he was twelve. For most of his life, Murray blamed the class-snobbery of a doctor at Taree hospital for refusing to send an ambulance but – as so often with Murray’s mythologising – the truth was muddier, sadder and more human. His father Cecil refused to drive her to hospital or explain her situation to doctors or relatives for a range of traditionally masculine and familial reasons. Grief reduced Cecil to a husk, and for much of this period Murray was either caring for his father or wandering the farm alone, abandoned to the psychological wasteland of his own loss.

Pseudo-psychoanalytic criticism has a lot of bullshit to answer for over the last forty years, but in Murray’s case it seems clear that some of the darkest strains of his work link to this period, and foment in his next years at Taree High, where he had an Objectively Shit Time. At points here, and throughout his youth he would take a rifle and walk or ride through the bush shooting most things that moved. He wrote about it in a number of different registers. In Poems Against Economics (1972), there’s an entire poem about a first world war rifle ‘SMLE’ (Short Magazine Lee-Enfield), and in an otherwise unpublished poem included in Peter Alexander’s borderline-sycophantic 2000 biography, he writes about a hawk:

He pivoted and hung, and hunted

Till I shot him with my dark

Rifle from where I sat my saddle:

I see him yet, a wrecked thing drifting

Down the ringing air, and IFull of deepest heart’s own winter

Ride to pick my eagle up… (70)

The taint of regret recalls Coleridge, but what hangs in the poem’s echo is the violence itself, more like Ted Hughes’ ‘Hawk in the Rain’. Murray’s and Hughes’ poetry have many things in common, incidentally, and the latter was responsible for Murray being awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 1998. In European traditions from Homer down, lots of poets have been fascinated and compelled by violence, force, action – it’s not uncomplicatedly a criticism, to my mind. In ‘The Abomination’ (1969) the speaker transforms the morning task of killing trapped rabbits into a chthonic ritual, sacrificing an animal to the infernal embers of a stump-hole fire. On the text’s surface the rabbit is already dead, but there’s a visceral sense of horror or shame in this poem’s bowels that speaks other contemplations:

… Here I killed

one final time, and slung my heavy bag

to approach the blaze – as I had known I would.Behind the black terrazzo of old heat

Light glared from crumbling pits. Old roots are tough

But when they catch, their blinding rings each deep

And rage for months and suck your breath away

If you kneel before them too long, peering in…as I knew I had by the pallor of the sky.

Scrambling up to go, I told myself

no harm in this. I was just looking down

to see how far back the earth might be unsafe.

it wouldn’t do to break through on such heat.Budded with light on light, the butts of glare

in their fire-burrows were a deeper fact

that stared down my evasions, and I found

a rabbit in my hands and, in my mind,

an ancient thing. And it was quickly done.Afterwards, I tramped the smoking crust

heavily in on fire, stench and beast

to seal them darkly under with my fear

and all the things my sacrifice might mean

hastily performed past all repair.

This poem gets interesting at ‘as I had known I would’, as it leans towards a compulsion or a ritual. Within its own pastoral lens, it enacts a kind of nekyia, an ancient Greek form of cultic communion with the nether-world. However, rather than to ghosts per se, the speaker fearfully seems to offer sacrifice to darker atavisms. This one also recalls Hughes – the final image of ‘Pike’ (1995): ‘… the dream / Darkness beneath night’s darkness had freed,/ That rose slowly towards me, watching.’ What is the abomination here, the act, the glimpsed depths of hell, or the possibilities of the speaker’s own mind? As a prodigious linguist, and a catholic, I expect Murray knew that abominatio comes from the hatred or fear of corruption from pagan idols but, like Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz, the speakers in these poems finally know where the horror comes from. This last point is part of an implicit critique made by John Kinsella in ‘The Hunt’ (1998) (a poem dedicated to Murray), in which rural brothers pursue one of Australia’s crypto-mythological big cats to pay their dues to the patriarchal symbolic order. They succeed, after a fashion, but – like the speaker of ‘The Abomination’ – they’re left with a classical sense of miasma, an indelible stain of transgression.

This ugly vein of Murray’s work probably reaches its most feverish in his angriest book Subhuman Redneck Poems (1996), interestingly enough also the one that got him the TS Eliot prize. Here and elsewhere where he writes about high-school trauma there’s an almost childish depth and purity of pain, and unrefined fury, that bleeds off the page, even from texts written decades after the experience. Probably the worst, in several senses of the word, is ‘Rock Music’. This poem is an easy target for a polemic, it attracts Murray’s critics, and his acolytes tend to give it a wide and diplomatic berth:

Sex is a Nazi. The students all knew

this at your school. To it, everyone’s subhuman

for parts of their lives. Some are all their lives.

You’ll be one of those if these things worry you.The beautiful Nazis, why are they so cruel?

Why, to castrate the aberrant, the original, the wounded

who might change our species and make obsolete

the true race. Which is those who never leave school.For the truth, we are silent. For the flattering dream,

In massed farting reassurance, we spasm and scream,

but what is a Nazi but sex pitched at crowds?It’s the Calvin SS: you are what you’ve got

And you’ll wrinkle and fawn and work after you’re shot

though tears pour in secret from the hot indoor clouds.

This poem is obviously fucked. Like Sylvia Plath’s ‘Daddy’ – technically a very strong poem – it translates a global atrocity into a metaphor for private loss and private trauma. I doubt anyone can find a poem that manages that without grossly trivialising the former. At a conceptual level the text’s connection are distorted, spasmodic almost. It pivots too smoothly from to the fascist mastery of a particular aesthetic to a closing image that blurs the agony of the solitary teenager with that of the gas chamber. The inequity of eros elides race, slaughter, genocide, ie: the whole Shoah. As I said, this is an easy target, but poets get remembered for their worst as well as their best.

Other commentators, including sympathetic ones, have noticed a discomforting affinity between this theme in Murray and the digital men’s rights’ activist or ‘incel’ phenomenon (which should only ever be used in scare quotes). But this does slant towards self-awareness of a kind in his work. From the later poem ‘A Torturer’s Apprenticeship’: ‘But for the blood-starred spoor/ he found, this one might have made dark news.’ Ironically enough – given Murray’s problems with feminism –this gradual progress from subterranean rage and confusion that gradually moves through the difficulties of self-awareness and forgiveness, particularly notable in his second verse novel Freddy Neptune (1998), could be read and taught hypothetically as a powerful critique of the insidious dangers of toxic masculinity.

***

‘An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow’ is among Murray’s most anthologised and syllabised poems, such that it’s hard to encounter the actual poem through the culture-fog and even the poet came to resent its popularity (Alexander, 74). It’s from The Weatherboard Cathedral (1969) but what strikes first is the poem’s deliberately belated temporality: historically, its urbanities make more sense in a Slessor poem from the 30’s. Content-wise, it’s about an anonymous man who weeps in Martin Place and effects an almost Christic halt to the bustle of Sydney:

The man we surround, the man no one approaches

simply weeps, and does not cover it, weeps

not like a child, not like the wind, like a man

and does not declaim it, nor beat his breast, nor even

sob very loudly – yet the dignity of his weepingholds us back from his space, the hollow he makes about him

in the midday light, in his pentagram of sorrow,

and uniforms back in the crowd who tried to seize him

stare out at him, and feel, with amazement, their minds

longing for tears as children for a rainbow.

In terms of imagism, this poem has its moments – ‘pentagram of sorrow’ and, later, ‘his writhen face and ordinary body’ – but this poem gets its effect from the strength of its content, aligning suffering and vulnerability with a striking depth of dignity. Today, I’ll only note that it would be strange to find only one person weeping in Martin Place.

You’ll also find a lot of landscape or ‘eco-poetic’ poems among his more celebrated. ‘The Gum Forest’ from Ethic Radio (1970) has some brilliant image-work:

Foliage builds like a layering splash: ground water

drily upheld in edge-on, wax-rolled, gall-puckered

leaves upon leaves. The shoal life of parrots up there.

Leafing (another Murrayism) through his books at random, you find rural imitations and pretty execrable Robert Burns impressions shouldering up against discursive and preachy ‘philosophic’ poems like ‘Politics and Art’:

Brutal policy,

like inferior art, knows

whose fault it all is.

The sentiment of which is kind-of true I guess, but doesn’t putting it in a poem contradict the whole point &c? And most lingeringly, some of the stark, estranged-eye imagery we associate with Modernism. This section is pretty good, ‘Antarctica’ (2007):

the planet revolves in a cold book.

It turns one numb white page a year.

Round this in shattered billions spread

ruins of a Ptolemaic sphere,

***

During the bathos of the stupidly titled ‘poetry wars’, Murray would come to be polarised against the American inspired experimental poetry exemplified at the time by people like Adamson, Forbes, and Tranter, but he and Bob Ellis shared a room for a time and, like many others, he squatted in a Sydney Push share-house in Milson’s Point. At school, his exclusion from the cult of beauty and popularity impelled an embrace of another cult, the cadets, and with it his fascination with all things military. Here, too, a few abrasive encounters with the ’68 poets – hardly saints themselves, cf. Kate Lilley’s Tilt (2018) – accreted into the binary mythos of Murray’s world-view. This can be thought of as a more sophisticated and more paranoid version of the old Sydney and the Bush dichotomy. At one pole, he saw everything he hated about modernity: sneering cosmopolitanism, cynicism, atheism, fascism, communism, feminism and a lot of things about sex. At the other, there was honesty, spirituality, humility, tradition, and – weirdly enough – Indigeneity again (which I’ll discuss more below). In other words, it was bullshit: a towering heap of the formation he despised so often in others – ideology, but nonetheless an ur-narrative which his otherwise subtle exegetic mind could acrobatically deploy to justify some deeply contorted loyalties. You can find some evidence of this adolescent logic in most of Murray’s books but, as mentioned above, it’s most obvious in Subhuman Redneck Poems (1996). Some of these poems are so fucked up that they don’t warrant the name or the attention – hate is a powerful stimulant but even Murray’s abilities could strain trying to turn it into art. Here’s an excerpt from ‘The Demo’:

Whatever class is your screen

I’m from several lower.

To your rigged fashions, I’m pariah.

Nothing a mob does is clean,not at first, not when slowed to a media,

not when police. The first demos I saw,

before placards, were against me,

alone, for two years, with chants,every day, with half-conciliatory

needling in between, and aloof

moral cowardice holding skirts away.

I learned your world order then.

Murray’s sense of affective exclusion and sexual exile blurs groups into a single, hostile entity and a protest against oppression turns into a mob, definitionally a force of oppression. This etiolated sense of victimisation explains a lot about Murray, and perhaps about Australian conservativism generally. Murray’s 1999 poem ‘A Deployment of Fashion’ starts by resonantly criticising the rampant misogyny of Australian public life, but ends up defending Pauline Hanson and somehow translating Helen Darville into a crucified victim instead of the kind of vicious hack who who pretended to be Helen Demidenko to make her racist book sound less racist and recently salivated on twitter over the prospect of Greta Thunberg having a spectrum-meltdown.

As Le emphasises, strong poets create their own myths and define their own subjectivities. While Murray’s subjectivity was intricately informed by his earlier experiences of social relegation – some of which I share and sympathise with – for much of his career that myth was articulated from a position of power, prestige, and hegemony. As Le puts it, he was top dog. In their excellent study of the culture wars The Virtual Republic (1997), McKenzie Wark makes the same point about Murray’s idea of a vernacular republic:

A key point Murray makes in his ‘republic’ essay is that various squabbling factions of the Ascendancy will never admit that they all belong to the same class. Each claims to speak for the public interest, and each tries to exclude other claims to articulate the common world. My only dissent is that I think we need to include Murray himself as well, even though he would like to appear as the ‘peasant mandarin’ somehow outside that social class of talking heads who populate the world of appearances. (265)

More, this myth, with the intricacy which a mind like Murray’s could give it, lent cover and capital to the saurian minds at Quadrant, which far from a site of relegation was for much of that time the mouth-piece of the conservative wing of a ruling political party.

This passage from Wark wasn’t written specifically about Murray, Quadrant, or The Ramsay Centre for that mind, but it works all the same:

I don’t miss the cold war, but clearly some people do. Needing some polar axis to cling to, in needing to believe someone is still listening, old cold warriors crank up the old drill of the ‘present danger’. Only the Reds aren’t lining up on the other side any more. So ghostly images of them have to be conjured out of half-remembered ‘security assessments.’ (209)

Quadrant was funded by CIA Kulturkampf loot shelled out to prevent the cultural spread of communism in the pacific. Under the inaugural editorship of the poet James Macauley, it established a legacy of embattled contrarian and conservative Catholicism, which Murray’s contribution as the magazine’s literary editor between 1991 and 2018 continued.

Quadrant’s always had a reactionary slant but there were periods when it was a serious journal devoted to actual discourse – and in turn capable of being taken seriously by a fair-minded reader. In 2007, the pseudo-historian Keith Windschuttle – think a semi-academic version of John Howard – assumed the editorship. During his crazed tenure, Quadrant gradually warped into something closer to the murky parts of reddit than a journal of critique. Even Murray’s polemical writing is nowhere near as bad as the average piece of barbarians-at-the-gates pearl-clutching you’ll find in Quadrant. His essays almost always maintained argumentative subtlety and a degree of irony, but nonetheless he was happy enough to suspend those standards by association and, by doing so, dignify truly indefensible positions.

This isn’t a new take: when Murray invited him to submit poetry to Quadrant in 1990, Tranter replied:

the publishing of literature in Quadrant [has] other purposes than the disinterested support of writing … the poetry has always been at the best window-dressing, and at the worst a way of making the magazine’s other purposes look as though they had the implicit support of its best literary contributors. (in Alexander, 240)

I don’t uncomplicatedly support de-platforming or the like as a reflex action, but from where I stand, the decision taken in 2014 by then Poetry Editor of Overland Peter Minter not to publish poets who also published in Quadrant was irrefutably the right one. It’s Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance – if you can’t accept the diversity of voices in the room then fuck off out of the room.

There are worse, much worse, contortions in Murray’s relationship with Indigenous culture. On the one hand, he claimed to respect a particular archival version of Aboriginal knowledge, but it was a purely historical or anthropological version which precluded a material acknowledgement or engagement with the ongoing realities of Aboriginal experience. The nakedly expropriative way he deploys cultural terminology – think of the ‘dreaming silence’ in which the persona contemplates his Scots ancestors in ‘Noonday Axeman’ – rigidly positions ‘the Aboriginals’ as a subject of rather than a participant in literary discussion.

Inevitably, this takes me to one of Murray’s best-known poems, the much celebrated ‘Buladelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’ published in Ethnic Radio (1977). According to Le, this is ‘the seminal poem of modern Australia’ and if Murray had written no other good poetry, it would still render its collection ‘one of the great books of the modern world’ (in terms he borrows from Clive James).

According to a deeply problematic essay Murray published in Meanjin in 1977, he was inspired to write this poem by the anthropologist Ronald Berndt’s translation of one of the Wonguri Mandjigai people’s Dreamings, The Song Cycle of the Moon Bone. Murray praised this translation for the way it renders Aboriginal poetry ‘deeply in tune with the best Australian vernacular speech’ and that priority is a big part of the problem.

In an article I published last year in Australian Literary Studies, I argued that Australian Literature is intricately involved with the containment and erasure of Aboriginal people, as a late stage of what Patrick Wolfe calls a logic of elimination. ‘The Buladelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’ is an extremely sophisticated version of that elimination: it appropriates the cadence and the ideas of Aboriginal culture to describe and praise the white Australian society which tried so hard to eliminate it.

The Jindyworobaks were culturally and politically misguided, but thankfully they were also on the whole shithouse poets. Murray was similiarly misguided, but his poetic mind was generally exceptionally strong, and this poem is technically a good one in a number of ways.

There are big claims being made about Murray and his times, here’s mine: ‘The Buladelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’ poem is also uncomplicatedly evil. It’s a chilling glimpse of the complete success of the logics of elimination identified by Wolfe. It illustrates an Australian culture of successful genocide, one which has completely absorbed the signifiers of the culture it destroyed. Given the way canons work, Murray’s poetry probably isn’t going anywhere, and I imagine this poem will continue to be read and taught, but, if so, it should be taught in tandem with the real thing: writing from the culture it steals from. Bill Neidjie’s Story About Feeling (1989) comes to mind. And, most importantly, it should be taught as an example of the ways in which Australian writing has participated and continues to participate in the legitimation of a colonial project on the Australian continent, and as an example of poetry’s unique power to tell beautiful lies.

***

A book where Murray did meaningfully contribute to ethical representation is Killing the Black Dog (2009), his vivid memoir on living with major depression. Today, most people with neurologically diverse experiences don’t conceptualise mental illness the way he did. Nonetheless, this book contributed to a destigmatised conversation. When the symptoms of my own conditions were first presenting, in my late teens and early twenties, I, like Murray, was a working class kid trying and failing – sometimes literally, if we’re talking about marks – to navigate the bastion of slick privilege that was and continues to be Sydney University. That book spoke to me, and the marrow-deep rage of some of his worst poems makes terrible sense in stages of psychological extremity. Its targets are undeserved, and its connections are false, but it’s bitterly true that there are few further exiled from the communities of human kindness than the mad. Of course, the book couldn’t have given the same comfort to the many other kinds of people who struggle with mental illness in modern Australia, most of all the Aboriginal people who continue to be horrifically over-represented in prisons, asylums, and suicide statistics.

***

So, what now? Murray leaves a legacy of strong writing which, like much Australian literature, is tainted by indefensible principles and politics. These are the facts of our history, and we know too much now to simply celebrate it, even when it’s well-written. On the other hand, ignoring or repressing this legacy plays into the hands of the cult of forgetfulness that already dominates Australian historical sensibility, and concedes a lot of ground to the wonks at the Ramsay Centre – who, I note, include both ‘The Buladelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’ and The Song Cycle of the Moon Bone in their hypothetical curriculum. For the settler mind, this is a conceptual problem, an antinomy, a contradiction between laws or axioms. For my money, white Australian thought doesn’t have an answer and is probably structured so as not to have an answer. Every piece of competent art – or writing about art – to some extent legitimates, allegorises and reifies the context in which it was produced. This is true even of the best and most critical Australian writing, in a local version of the paradoxes of political art identified by Jacques Ranciere and Fredric Jameson. In attempting a sophisticated critique, exorcism and recapitulation of a certain version of the textual product labelled ‘Murray’ on the shelves of our bookshops and libraries, I imagine I’ve done the same thing.

To end on a hopeful note, and with the Uluru statement in mind, the breadth and vigour of diverse writing published here in the last twenty years is changing things. Conspicuously, the boom of Indigenous literature represented by people like Alexis Wright, Melissa Lucashenko, Tony Birch, Jeanine Leane and younger poets like Alison Whittaker and Evelyn Araluen seems like it might be gesturing to a time when we can appreciate the good in Murray’s work without endorsing the rest, and without silencing other voices – in the same way we can talk about Eliot’s mastery of cadence in The Waste Land without subscribing to his antisemitism. For me, we’re not even close to being there, and it will be an Aboriginal critic who decides when we are. If that’s a cop out, then it’s a cop out.

***

Embittered Postscript: I came up with this critical experiment before the catastrophic national idiocy we witnessed during the recent election. In light of that, I’m sad to say that the movements towards balance and synthesis I’ve attempted above seem grossly optimistic, naive, and pretty much fucking utopian. Rather than just delete them, I’ll let them stand as spectral gestures of the possibility of a just and decent Australia honestly committed to addressing the wrongs of its past, and the fragility of its future. The one we glimpsed – just glimpsed – in moments of the Whitlam, Hawke, and Keating governments. But for now, they need a bleak, sober, sad revision: Murray lived, he wrote some good poems, he was very wrong about some very important things, and he died at a venerable age that most Aboriginal people today will never approach. In the words of Murray’s lord, let the dead bury the dead.

Alexander, Peter f. Les Murray: a Life in Progress, Oxford UP, 2000.

Bourke, Lawrence. A Vivid Steady State: Les Murray and Australian Poetry. New South Wales UP & New Endeavour Press, 1992.

Clunies Ross, Bruce & Hergenhan, Laurie ed. The Poetry of Les Murray. Australian Literary Studies & University of Queensland UP, 2001.

Hughes, Ted. New & Selected Poems 1957-1994. Faber, 1995.

Jakobson, Roman ‘What Is Poetry?’ v. 3; O. Paz, The Bow and the Lyre, trans. R.L.C. Simms, 1973.

Image: David Naseby, Les Murray (detail)