Stop tryna be God. – Travis Scott

Not every Pacific Islander feels a connection to the ocean. Although I recognise that the South Pacific Ocean is a deep spiritual place for us, the closest body of water I grew up around as a third-generation mixed-race Tongan-Australian woman from Mount Druitt was a dirt-black pond filled with dumped Woolies trolleys, mosquito eggs and a dead body. However, even within the suburbs of Western Sydney, I was constantly followed by the Island girl stereotype: ‘Will you wear a hula skirt and coconut bra at our wedding?’ my Anglo ex-boyfriend Matt asked me after three weeks of dating. ‘I thought all Islanders could sing,’ my Irish-Scottish music teacher scoffed at me when I told her my only musical talent was tapping a triangle off-beat. Growing up, I hated identifying as Tongan, so every time these stereotypes were attributed to me, I’d shake my head and say, ‘No, you don’t understand, I’m half White.’

It took me a long time to feel empowered by my Tongan heritage and even longer to become critical of the Western narratives surrounding it. I know now that typecasts about Pacific Islanders, and especially in my case, Pacific Islander women, are part of a colonial, imperial, capitalist and patriarchal construction of exotic primitivism, which is known as the ‘Pacific muse’. In The Pacific Muse: Exotic Femininity and the Colonial Pacific, Patty O’Brien defines this as the idea that

Pacific peoples [are] blessed by nature’s bounty, living healthy, natural lives in addition to being leisured, beautiful, and sexually alluring. Yet [when compared with reality] the contemporary Pacific is a troubled region, marred by poverty, environmental problems, poor health, and instability in indigenous politics across the region.

Much like the racist constructions of the ‘violent’ African and the ‘terrorist’ Arab, the ‘Pacific muse’ continues to be thought of in the West as a factual portrayal of South Pacific women.

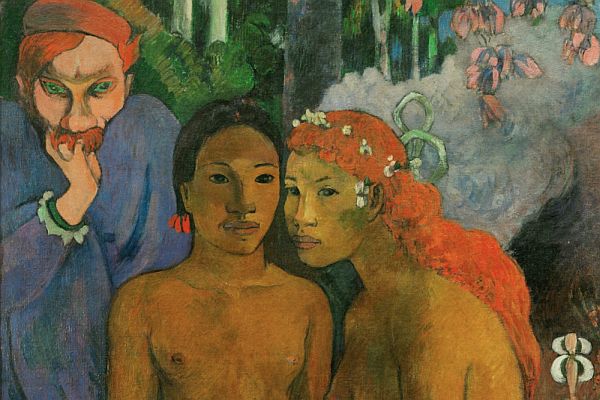

This stereotype of Pacific women is most noticeable in the artworks of French post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, who sailed to Tahiti in 1891. His motives were laid bare in a letter he wrote to Vincent van Gogh:

At the atelier of the Tropics, I will perhaps become the Saint John the Baptist of the painting of the future, invigorated there by a more natural, more primitive, and above all, less spoiled life.

It was the indigenous women of Tahiti that became Gauguin’s Pacific muses. In Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892) Gauguin depicts his thirteen year old native wife Teha‘amana lying nude in a bed of Tahitian cloths with Tupapau waiting above her. Gauguin wrote extensively about the painting in his fabricated travelogue entitled Noa Noa, where the occult local legends it relates to were lifted from Dutch ethnographic accounts as well as photographs of South-East Asian art he brought from France. In Noa Noa, Gauguin claimed that his painting depicts Teha‘amana’s fear of seeing Gauguin return home in the middle of the night and mistaking him for the spirit of death. I find this ironic because Gauguin took on three teenage Tahitian wives and infected them all with syphilis before dying of syphilitic complications himself.

All of Gauguin’s artworks about Tahiti contribute to the damaging stereotypes about the Pacific and the people who call themselves Polynesian – a sexual and racial fantasy forged from a position of patriarchal and colonial power. This is what it means to be constructed as a Pacific muse. The South Pacific islands are constantly viewed by the West as mysterious and paradisal palm-fringed and coconut-filled beaches, complete with Brown-skinned, savage-warrior men and loose indigenous women. However, as Patty O’Brien has outlined, every island in Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia is marred by imperialism, poverty, poor health, unstable governments, erasure of indigenous cultures and the immediate threat of global warming.

The most prominent and current example of the Pacific muse archetype can be found in the 2016 Disney animated film, Moana. Moana, which is loosely based on traditional and ancient oral stories about the ancient trickster called Māui, was directed by John Musker and Ron Clements. Both directors had previously worked on the animated Disney film Aladdin, which has faced strong criticisms by Dr Jack Shaheen in his book and documentary series of the same name, Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People. Shaheen argues that Aladdin depicts racist and orientalist stereotypes about Arab and Muslim people and lands, which has had-long lasting and damaging impacts on Arab and Muslim communities worldwide ever since its release, in 1992. When interviewed about the origin and success of Moana, Musker and Clements boasted about having conducted five years’ worth of research before undertaking the animation, including a three-week field trip to Fiji, Samoa and Tahiti. ‘The word boondoggle was passed around,’ Musker told the Hollywood Reporter after joking about his relaxing all-expenses-paid field trip to the South Pacific. Musker continued, ‘In the original version of the story, Moana was the only girl in a family of a lot of boys, and gender played into the story. But that all changed. It was decided gender shouldn’t be her problem, it should be realising her own self.’

Throughout the interview, Musker and Clements continually replaced the details in these indigenous stories for their own ideas and values on what makes a ‘good’ narrative. Disney is the second-largest media conglomerate in the world and has the power to shape how every country, continent and island understands Polynesia and its different cultures. In this way, Moana is a film that displaces hundreds of different South Pacific orations passed down for thousands of years in favour of a White male retelling. This reveals the glaring contradiction in the way these men always think: they want to know us and at the same time they want to tell us who we are.

In the same Hollywood Reporter interview, Musker and Clements were asked what Disney’s Moana has in common with Disney’s Jasmine, whom the two directors also ‘created’. Musker joked: ‘In a physical bout, I think [Moana] could take Jasmine [laughter].’ As a young woman of colour, it made me incredibly uncomfortable reading about two rich White men making jokes about who would win in a mud-wrestle between an Arab woman and a Polynesian woman. Perhaps it was subconscious on Musker’s part, but I couldn’t help noticing that – in comparing the physical capabilities of Jasmine and Moana – he had reproduced the stereotypes of Arab women as weak and submissive and Polynesian women as unusually strong, violent and aggressive. Are these men really the right people to be in control of a story about women of colour?

Whilst the Pacific muse stereotype impacts all Pacific peoples on an international level, the dominant portrayal of Polynesians, Melanesians and Micronesians in Australia today directly impacts our communities on a local level. I am referring specifically here to Chris Lilley’s ABC programs, Summer Heights High and Jonah from Tonga. Both mockumentaries feature Jonah Takalua, a fictional Tongan-Australian boy played by Chris Lilley in Brownface. In every episode, Jonah is depicted as an abusive, disruptive, gang-affiliated individual on welfare with learning difficulties and hypersexual cravings, which include lusting over his cousin. At the height of Chris Lilley’s success, many Tongans spoke out against his use of Brownface and racial profiling using the hashtag #MyNameIsNotJonah. Prominent and everyday Tongans like Miss Face of Beauty International Diamond Langi, Tokateu Lolotonga, Leitu Hevea, Salote Taulalau, Katie Pohahau and David Ware publicly spoke about their various and unique experiences as diasporic Tongans. Katie Pohahau proclaimed on Facebook:

I am a proud Tongan. I was never suspended from school. I am currently studying at ACU for my bachelor’s degree in nursing. Judging people does not define who they are. It defines who you are.

David Ware wrote on Instagram:

I grew up in a rough neighbourhood. I got in trouble with the police. I experimented with substances. I didn’t even finish 10th grade. I worked in factories and laboured in steel yards. I never got my licence ‘till I was in my 20s and guess what… my name still isn’t Jonah.

While Tongan-Australians spoke out against Jonah from Tonga, ABC TV’s Head of Comedy, Rick Kalowski, defended Lilley’s work claiming that ‘the series does not encourage or condone prejudice. It is important to note that no other Tongan characters in the show are presented in a buffoonish light, other than Jonah himself.’ He was wrong. Each of Jonah’s friends, Leon, Joseph, Thomas and Ofa are the same-illiterate, hypersexualised bullies as Jonah. In every other scene, Jonah and his friends are being harassed by White teachers for being disruptive, requiring assisted-learning programs and being bullies. On every account, in every character connected to Polynesian identities in Lilley’s work, we see the same blatantly racist and stereotypical portrayal of Brown-skinned people. But even if Kalowski was right and it was just Jonah himself, one lead White man in Brownface enacting racist Tongan tropes is one White man too many.

When non-Polynesians represent people from the South Pacific, they play God with our lives and stories: they construct fantasies about palm trees, oceans, fresh air, fit Brown women in coconut bras and large Brown men yielding spears. At the heart of this issue is the fact that we are not the storytellers. As Nalini Mohabir wrote in the Guardian, ‘independence does not need to be a grandiose process of disconnection and severing ties.’ Rather, it is the possibility to ‘reclaim ancestral legacies and envision new futures – futures that do not belong to the limited choices laid out by colonialism that foreclose true independence, but a more hopeful map for the next generation that opens up the spirit of liberation.’ Whilst I have no real connection to the South Pacific Ocean as a place, I do have a bond to the shores of Mount Druitt. My life as a Tongan-Australian is lined with Maccas and KFCs, 7/11s and abandoned buildings, the textbooks I borrowed for class at Western Sydney University library, Starbucks and a 24-hour Kmart, derro housos where TNs hang from powerlines and a Westfields where every second store is stocked up with bumbags for the adlayz and phreshies just like me.

Image: Paul Gauguin, ‘Barbarian tales’ (detail)