In 1994, Keith Windschuttle published The Killing of History: How a Discipline is Being Murdered by Literary Critics and Social Theorists. The book’s ungainly title conveyed a breathless urgency, implying an impossible present in which the discipline is at once alive and dead (at what precise moment is one being murdered?). Appropriately, it embodied conservatism’s central contradiction – the belief that the Left constitutes an immediate existential threat to societal wellbeing, and that the Right is on the cusp of oblivion and must be saved now or forever lost. Therefore, each battle is to be fought with the desperation and tenacity of the Charge of the Light Brigade or the final act of an Avengers sequel: it must be understood that absolutely everything – which usually means an ahistorical reading of Western Civilisation – is on the line.

In The Killing of History, Windschuttle fears the destructive onset of the ‘new humanities.’ Among this movement’s principles, he writes, is that ‘different intellectual and political movements create their own forms of relative “knowledge”,’ and that ‘truth is also a relative rather than absolute concept.’ It is ironic, then, that on Sunday, Windschuttle published in Quadrant – the magazine of which he is editor-in-chief – an essay premised on the assumption that the quality of a claim to truth depends on its compatibility with a system in which the powerful deserve their power.

The contention of ‘The Borrowed Testimony that Convicted George Pell’ is that the Pell case resembles that of Reverend Charles Engelhardt, a Philadelphia clergyman who died in prison in 2014, before the credibility of the victim and star witness who led to his conviction was thrown into doubt by a 2016 investigative report in Newsweek. Windschuttle lists seven similarities between Pell’s case and the American case, including that in both instances the boys were caught drinking wine in the sacristy, forced to kneel before the accused and perform fellatio, and were the lone witnesses. That these features do not seem especially conspicuous – given that both cases rested on stories of sexual assault by a member of the clergy in a church, and that predation often follows similar patterns – does not appear to bother Windschuttle. He is sufficiently convinced by his own detective work to conclude that ‘the two accounts are so close to being identical that the likelihood of the Australian version being original is most implausible,’ and that therefore, Pell’s accuser was ‘repeating a story he had found in a magazine – or repeating a story someone else had found for him in the media’ (the case had been first covered in 2011 by Rolling Stone, which he helpfully dubs ‘an American magazine dedicated to popular culture, targeted at teenagers and young adults’).

Windschuttle concedes that his conviction that the story of Pell’s sexual assault is ‘a sham’ ‘does not mean the accuser was deliberately making it up.’ This rhetorical manoeuvre brings to mind the arguments made by Republicans during the battle for Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination. Attempting to dodge the appearance of cruelty, they patronised and ignored Christine Blasey Ford rather than stating outright that they disbelieved her. Perhaps, they suggested, she had simply convinced herself that Kavanaugh attacked her. The position evinces a false generosity, contingent on a refusal to commit to the legal tenet that testimony is, in fact, evidence, when such a commitment becomes inconvenient. The testimonies against Justice Kavanaugh and Cardinal Pell are inconvenient because they reveal the fraudulence of the ruling class’s insistence that there can be such a thing as neoliberal meritocracy.

To read Windschuttle’s tempestuous defence of Pell is to witness the conspiratorial logic of contemporary conservatism forcefully deployed. It is increasingly obvious that the ideological ground occupied by Quadrant, Fox News, Quillette, The Australian, Sky News, Infowars et al. is founded on the same essential creed: under the banner of identity politics, the Left is undertaking a deliberate campaign to police speech and behaviour in order to create a society in which conservative dissent is erased (the belief that the Left is currently well-organised enough to accomplish such a task is not the least specious element of this paranoid fantasy). This creed masks a white nationalist vision, concealing frequently racist arguments within a vocabulary of rights and free speech. It’s no coincidence that, in 2002, Windschuttle published The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One, in which he maintained that Indigenous Australians had no concept of ownership, and that therefore it makes no sense to describe colonised Australia as stolen land. He has also repeatedly argued that there never was a Stolen Generation. These debates tend to return to questions of race because the structure that publications such as Quadrant exist to sanitise and justify is white supremacy.

The safeguarding of Pell’s innocence is another manifestation of this anxious desire to secure the power structures as they are, that is, a world in which old white men can dine with one another in peace, safe from resentment and safe from the law. Those who’ve rallied to Pell’s defence are irked by the revelation that a Cardinal who stalked the halls of the Vatican, consulted with prime ministers and dined with US agency chiefs at Michelin-starred restaurants can be punished like some ordinary citizen. Even more humiliating than being imprisoned is being stripped of one’s emblems of supremacy. What chills Pell’s defenders is the prospect that, very occasionally, the armour of privilege does not provide total immunity.

Of course, juries can get it wrong and the question of whether trial-by-jury should be the predominant system for meting out justice is worthy of debate. But it’s disingenuous for Windschuttle to hold that, in defending Pell, justice is his primary concern. If that were the case, he could have considered what has led to Australia’s police and courts to preside over a prison system in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people comprise 28% of the prison population despite accounting for around 3% of the general population. He might have wondered why, as of 2018, all juvenile prisoners in the Northern Territory were Indigenous. Or perhaps he should have contemplated the data showing that only one in ten reports of sexual assault in Australia result in a conviction. But evidently, in the pages of Quadrant, justice is relative.

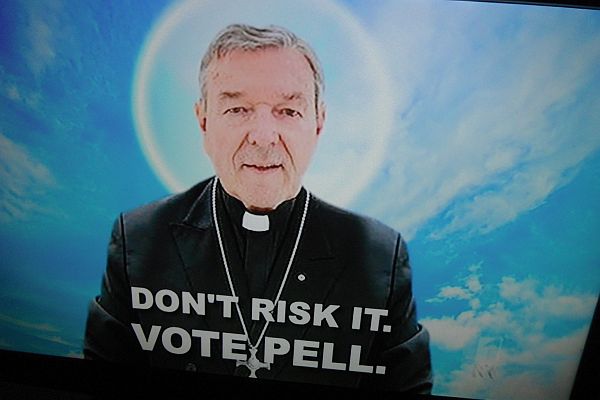

Image: RubyGoes