Text’s new edition of Helen Garner’s 1977 novel Monkey Grip is an opportunity to revisit the book’s influence on Melbourne. In addition to being widely considered a classic of Australian fiction, Monkey Grip is frequently referred to as an iconic ‘Melbourne’ novel. Certainly, it is a novel absolutely grounded in and shaped by place. Monkey Grip exhibits an intimacy with place that is built through local knowledge and the regular, routine movement through the spaces of one’s life. The city is much more than a backdrop to action. For Nora, the narrator and protagonist, it is the locus of the social encounter and emotional intensity on which the book’s narrative depends:

I chased them down Russell Street to Jimmy’s in the city. I ran in, eager for a sight of their familiarity. They were sitting at a table with Willy and Paddy, who had their backs to the door […] They were glad to see me and I sat down with them to eat. When we left the restaurant we walked up Russell Street, strung across the pavement, Gracie riding on Jack’s shoulders. I put my arm round Willy’s waist and he laid his over my shoulder […] Our boots beat the footpath in rhythm, and we walked back to Carlton in the cold spring night.

At the time, Garner’s focus on the domestic and on the geography of a local urban milieu was original in the field of Australian fiction: a Melbourne author writing about her community in the areas in which she lived her daily life. In her foreword to the new edition, Charlotte Wood focuses on these intimate landscapes in both Garner’s book and in her own reading of the book. Wood declares in her opening paragraph that Monkey Grip ‘makes me remember the person I was in my youth. Like all Garner’s work, it also makes me examine who I am now.’ Wood underscores that this is the reason for the book’s enduring appeal: ‘There it is, that willingness to own up and face the self, right from the start. As I said, Garner makes me look at who I am. I think this is why readers love her.’

Wood’s emphasis on the personal in the novel’s narrative and in her response to the book is important. After all, it is where Monkey Grip’s radical politics lie. Its narrative gave weight to the everyday lives of its characters, many of them women, by considering them worthy of literary treatment. As Wood points out, ‘Monkey Grip’s highly textured, perfectly rendered stray scenes speak of this loving impulse, to honour with delicacy and precision the beauty and pathos of ordinary life. Most especially, in this book, the ordinary life of women.’

Reading against the grain of appraisals such as Woods’ that focus on subjective experiences of Monkey Grip, there is another way of assessing its cultural and social legacy that acknowledges its impact on the city it portrays. Looking back, we can see that Monkey Grip gestures to a changing urban landscape in which the novel’s radical voice folded into increasingly normalised practices of counter-cultural inhabitation and property ownership in cities. In this light, the novel’s localism moves outward. Monkey Grip is also a globally familiar story of inner-city gentrification in previously working-class areas.

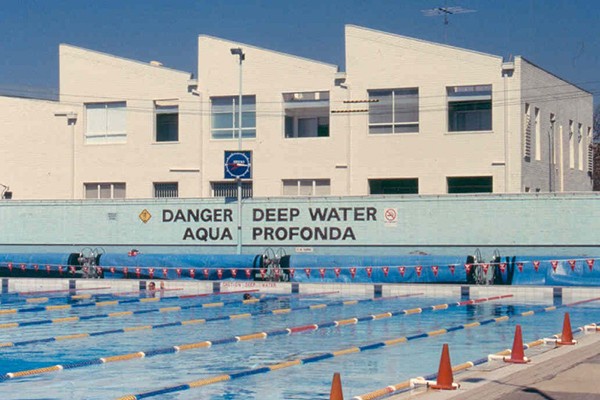

Monkey Grip is set in a counter-cultural community of the mid 1970s that emerged from the inner-city suburbs of North Melbourne, Carlton, Fitzroy and North Fitzroy – now known collectively and colloquially as the inner north. Nora moves back and forth along Lygon, Brunswick, Rathdowne, Napier and Peel Streets. The characters swim at the Fitzroy Pool, a still-popular spot. The book is scattered with the names of cafés, shops and venues, many of which survive and are now recognised Melbourne institutions: La Mama Theatre, Readings bookshop, the University Café.

Garner’s life is famously entangled with her writing. It is well known that she inhabited the places in which she located her characters, and that Monkey Grip reflected back the lives of her peers – the writers, artists, actors, musicians, students and academics who were drawn to Melbourne’s inner north by low rents. Garner lived in a terraced house in Carlton while working on the novel. The book was published by independent publishing house McPhee Gribble, who were located in another terrace house nearby on Drummond Street, Carlton. These nineteenth-century Victorian terraces accommodated the communal living portrayed in Monkey Grip. This way of living that reflected the ethos of Garner’s community is announced on the opening page of the novel:

There were never enough chairs for us all to sit up at the meal table; one or two of us always sat on the floor or on the kitchen step, plate on knee. It never occurred to us to teach the children to eat with a knife and fork. It was hunger and all sheer function: the noise, and clashing of plates, and people chewing with their mouths open and talking and laughing.

Amidst this collective focus, the novel also depicts the bourgeois milieu that underpinned its politically and socially radical aspects. Along with their shared housing, Garner’s characters inhabit spaces closely identified with inner-city culture and occupations in the creative industries:

Gracie and I went to the theatre and stayed there from seven in the evening until two in the morning. I danced […] Through the crowd I could glimpse Bill way up at the other end of the theatre, juggling three silver balls, his short dark head dipping and bobbing gracefully […] the theatre was full of people I like and loved and whose work was joyful to me.

Garner and her cohort were part of a gentrifying wave that began in Melbourne’s inner-city suburbs as the manufacturing industries that had previously populated the inner north moved out. The cultural milieu that Garner describes, combined with affordable real estate, were agents in the process of the inner north’s gentrification. David Ley’s work on urban transformation outlined that, ‘one of the strongest statistical predictors in the gentrification of post-industrial inner urban areas is a “first wave” of artists’. And, presumably, writers.

Today, Melbourne’s inner north is still associated with this lifestyle. Moving through the city’s streets or riding through Edinburgh Gardens in North Fitzroy just like Nora has become a reference point for contemporary creative practitioners in their portrayal of this part of Melbourne. Sophie Cunningham refers to it in her extended literary essay Melbourne, when she writes, ‘[a]s Garner has done some years earlier, I used to ride through the Edinburgh Gardens to the hundred-year-old Fitzroy Pool, a place where the water is not just deep but, as the sign says, profonda.’ Undoubtedly, it is no coincidence that Cunningham – whose literary career began in the offices of Garner’s publishers McPhee and Gribble – ended up in Carlton, just as it is no accident that Monkey Grip appears in Cunningham’s book.

Monkey Grip has also been folded into marketing vocabularies for the affluent suburbs in Melbourne’s inner north. The locations in the book now have some of the most expensive property in Melbourne. In 2011, the ‘old brown house on the corner, a mile from the middle of the city’ on the first page of novel sold for close to $3 million. The promotional material that accompanied this sale claimed that, ‘Helen Garner wrote the iconic Australian novel… while abiding [sic] under this roof’. Monkey Grip is, then, both a novel forged by place and an actor in the urban transformation of Melbourne’s inner north. The city Garner writes about isn’t only reflected in her writing. It’s been shaped by her novel and its resonance.

Image: ‘Aqua Profonda’ sign at Fitzroy Pool, Victorian Heritage Database