In February 1856, a stonemason wrote anonymously to the Sydney Morning Herald in support of shortening working hours. He hoped that soon ‘not one’ of his fellow tradesmen would be ‘working under the burning sun of Australia for more than eight hours a day.’ By April, Melbourne’s building trades had won a world-first: an eight-hour day with no reduction in pay. A year later another stonemason, Charles Jardine Don, pressed upon his audience the indignity of not extending the shorter day to every working man: ‘would you have him work,’ he asked, ‘until his heart breaks under the burning sun of this colony?’

More than a century and a half later, workers still feel the heat. You wouldn’t think it, though, reading much of the media’s recent coverage of the state of the Australian economy. Recently, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the monthly unemployment figures for September, revealing that the joblessness rate had fallen to five per cent for the first time in nearly seven years.

The announcement was covered extensively in the media, and was music to the ears of our newly minted Treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, who said that the lower figure was ‘something to celebrate’. Leaving aside the fact that the record low rate was mostly due a 0.3 per cent drop in the number of jobseekers, Frydenberg is right: lower unemployment is, on the face of it, a good thing.

But focusing solely on strong unemployment figures obscures an increasing reality for workers. Unlike Melbourne’s nineteenth-century stonemasons, the economic squeeze many feel today is not from overwork but its opposite: underemployment. As costs of living soar and wage growth remains dismally flat, a growing number of people struggle to find enough work to provide a dignified, comfortable existence for themselves or their families.

Underemployment – having a job but wanting to work more hours – has been increasing in Australia, particularly in the last four to five years. The latest ABS figures showed that 8.3 per cent of workers were underemployed, not far off the record 8.7 per cent set last February. That amounts to over a million people in Australia who feel they need more work to get by.

The problem is accentuated for particular demographics: women’s underemployment rate is above ten per cent, while my own generation suffers the worst from a lack of work – around eighteen per cent of twenty to twenty-four-year-olds are underemployed. Nearly one in three casual workers want more hours at their jobs.

This is a fairly recent phenomenon in Australia, as Greg Jericho has extensively detailed in his Guardian column. Underemployment was not a significant problem in Australia until the 1990s recession, when it spiked to seven per cent from a rate that had previously barely risen above four per cent.

Even then, Jericho writes, underemployment ‘only really became an issue’ around the turn of the millennium, when the number of underemployed overtook the number of unemployed. Now, at least 300 000 more people want more work than those out of work entirely, and in the last decade the underemployment rate has never dipped below the 1990s high water mark of seven per cent.

As the last while has illustrated, Australia’s media, policy-makers and politicians overwhelmingly focus on the unemployment figures as a measure of the economy’s success. But, as Jericho has written, unemployment figures no longer accurately represent ‘the real-world experience of the labour market.’ Unemployment may be at a record low, but that doesn’t mean most people are comfortably employed.

This is because since around 2014, the unemployment and underemployment rates have decoupled. Though unemployment has been falling, underemployment has, for the first time, not been falling with it, making the former a less reliable measure of the health of the labour market and the economy as a whole.

Why are we faced with this problem? The rise in underemployment has been driven by the huge growth in part-time work, which has more than doubled since the late 1970s and now represents about a third of the workforce. Unsurprisingly, more part-time workers mean more people unsatisfied with the number of hours they work.

Significantly, most underemployed part-timers do not simply want a few extra hours a week to supplement their income. Average hours for part-time workers have increased in recent years, but underemployment is still rising. Part-timers want full-time work. Why can’t they get it?

Clearly, there is not enough work to create full-time jobs for everyone in Australia. One reason for this is that governments no longer pursue policies geared towards full employment. But the more fundamental reason for the increase in part-time jobs is that our economy is staggeringly more productive than it was thirty or forty years ago.

Since the 1970s, we have had what academic Joshua Crook describes as a ‘productivity explosion’: for example, increased computing power has boosted office workers’ productivity by eighty-four per cent since 1970, while in the 1990s and early 2000s, improved agricultural technology allowed the farming sector to increase its output per worker by nearly half in just over a decade.

These mind-boggling, technology-led productivity increases show no sign of slowing down. A 2015 report by the Committee for the Economic Development of Australia suggested that forty per cent of the workforce is employed in jobs that ‘face the high probability of being replaced by computers in the next 10 to 15 years.’ Rather than an ominous statistic about the end of work, the prospect of further automation should be seen as a boon for our nation’s productivity.

But instead of reaping the rewards of our massively enhanced productive power, ordinary people are left in a set of precarious situations: too little work for the underemployed, barely reduced hours since the 1970s for full-time workers, and sluggish to non-existent wage growth for all.

What is to be done? Taking a leaf from Melbourne’s stonemasons sixteen decades ago, Australia should reduce the full-time working week to thirty hours, with no loss of pay. A thirty-hour week would increase the number of full-time jobs available, lowering both underemployment and unemployment, and would have the significant added benefit of increasing leisure time for the majority of workers. Close to full employment would also tighten the ‘slack’ in the labour market, tipping the scales in workers’ favour and increasing our currently anaemic wages growth.

After nearly seven decades of a thirty-eight to forty-hour week as the legal and economic norm, such a change would be culturally momentous but practically quite simple. As Godfrey Moase has written in The Sydney Morning Herald, we could simply amend the Fair Work Act to gradually lower the definition of full-time hours to thirty over an eight to ten year period.

Such a provision, Moase writes, should ensure wages rise with the cost of living, so that full-time workers see no dilution in their real wages. Our workplace laws will also need to be reformed so that employers cannot simply reclassify workers as casual employees or independent contractors to circumvent the new regulations.

Other nations and organisations have already made tentative steps towards a shorter working week: a New Zealand legal firm recently trialled a four-day week on full pay and found their workers were less stressed and more productive; earlier this year, German metal workers won the right to temporarily reduce their working week to only twenty-eight hours (with reduced pay); and in September the UK’s Trade Union Council announced that a four-day week was a realistic goal within this century.

Like the stonemasons’ victory 160 years ago, the shift to a thirty-hour week will require a strong union movement, and the support of Australian society at large. But if any reform can galvanise support – particularly among frustrated, disenfranchised young people – it is a society-wide push to change the horizons of our working lives. It may seem like a difficult task, but from the Eight Hours Movement to the Harvester judgement in 1907, Australian unions and governments have set precedents for leading the world in creating momentous change for workers.

There is a promise that a job should provide a comfortable, dignified life and regular leisure time to do as you please, but many are missing out on this. This injustice is the twenty-first century equivalent of the ‘burning sun’ the stonemasons condemned in the nineteenth. By shortening the working week to thirty hours with no reduction in pay, we can reprise the possibility of full, well-paid employment for the increasing number of us who find ourselves underemployed, and win the time and money to go out after work and enjoy a cold drink in the shade.

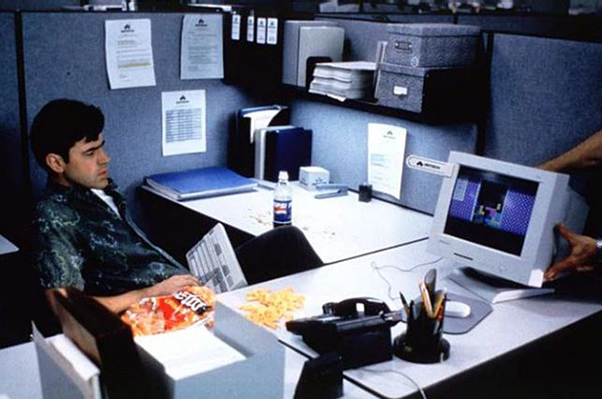

Image: Office Space, 1999