ASIO lied to me! Should I be shocked?

I had asked if I had an ASIO file.

In May 2014, after over 30 years of membership of a socialist group, when I applied for my file, ASIO, via the National Archives, denied that I had such a file. I mean the audacity of it! I have been arrested four times, charged twice. One good-behaviour bond and one conviction. I even had an interview at work for a security clearance in January 1996, with two ASIO agents, where I declared my aforementioned membership and my clearance was denied. (Hardly great for public service career advancement.)

My local Labor MP in Canberra, Steve Dargavel, called me in 1997 – I’ve hobnobbed with all and sundry on the left – to tell me that my name appeared on the Victoria Police list of ‘undesirables’ after The Age exposed that the Operations Intelligence Unit was still keeping files, after nominally being disbanded by Labor in 1983.

Steve was being friendly and informative, but was also miffed that my name and not his appeared in the online list – along with the organisers of the Teddy Bears Picnic. (I kid you not.) I was also batoned on my hand by Victoria Police in September 2000, at the World Economic Forum, when they had to ‘rescue’ WA Premier Richard Court and his driver from the crowds surrounding his car.

– Northcote residents against Kennett’s cuts. (Tom is on the right-hand side, with short hair and ski jumper)

So back to me and my file. Finally, in December 2016, the National Archives wrote that I did indeed have one. With that one bureaucratic fiat of an email I officially became a person of (as you will see) littler interest.

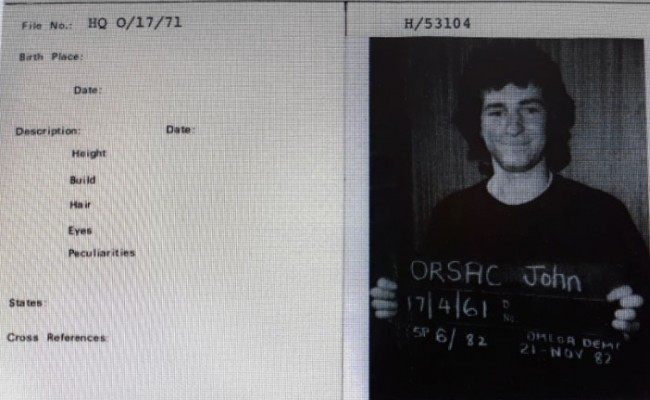

Skimming five thick redacted folders from 1982–1991 (even though the National Archives, under the 20-year rule, listed my file as continuing until 1994), looking for some gold dust about myself and my file number 0/17/71, is time-consuming.

What stands out, apart from the initial shock of violation of one’s life and privacy, is that after being a member for 34 years, ASIO’s surveillance has not impeded my activity as a socialist.

I have gone about the business. Age and life have just wearied me a little.

Not one article of what I have ever written for my group’s papers or magazines has been collated nor commented on. I am very miffed as I have a rather fine history of writing and a very incomplete index of it all. Would have been handy.

So while they have a file on almost anyone new to the left, these files are pointless. Indeed, they are a monstrous waste of time and resources.

What ASIO looks for, supposedly, is a ‘capacity towards violence’. Even if you get that label, you still can go unimpeded. You will most likely be, for instance, watched at demonstrations. According to my file, the Australian Federal Police sends lists from demonstrations of all known members of all left groups. It was nice seeing our rival left groups’ comrades’ names as well as ours.

Again, a monstrous waste of time and resources.

It’s almost as if because ASIO exists, the agency has a life of its own, outside any rationality. It is an amoeba. It just keeps on going. And collating information, reams of it, justifies the agency’s existence to its paymasters and is ‘make work’ for its agents and informants.

Who attends picket lines seems to hold no interest to them. I have attended scores, but the routine day-to-day of the class struggle is not as worthy as flashpoint ‘protests’.

– Protesting against Pauline Hanson 1997 in Canberra. (Tom is in the big overcoat with the megaphone, pointing)

As a 2008 Sydney Morning Herald article, rehashing the details of The Age 1997 story, noted: ‘Surveillance information was kept in a secret electronic database that had files on more than 1,200 Victorians ranging from gay activists to politicians, trade unionists, students, ethnic community leaders and environmentalists.’

ASIO’s brief has meant targeting the Labor side of politics, as if somehow even they are ‘disloyal’ to the conservative state. The far left is just lumped in for good measure. As I have written elsewhere: ‘ASIO entered a twilight zone of defining anyone left-wing, including the Labor Party, “subversive”.’

Conceivably, people who were so important to ASIO, whose hands were soiled with leftist ideas, might be too tainted, too extreme to hold the levers of state power. And yet one of those with a Victoria Police file was Peter Garrett, singer for Midnight Oil, and in 2008, also a federal cabinet minister.

Victoria Police’s files were estimated at ‘more than 1,200’. But David McKnight, in his books on ASIO, notes: ‘Until 1971, ASIO maintained a list of 10,000 “undesirables” to be interned in the event of war or a national emergency.’

That, I would argue, is the missing element from David Lockwood’s question in Overland #220, as to why ASIO wasted its time on him and the International Socialists, the group we were both members of at one time.

ASIO has a completely bureaucratic police mindset when it comes to understanding social explosions. Their approach is to simply round up all the potential ringleaders and intern them, a la Santiago stadium in Chile in September 1973.

Spies will never stop a genuine mass upheaval in society. The Okhrana could not save the Russian Tsar in 1917. SAVAK (trained by the CIA) could not save Iran’s Shah in 1979. The KGB could not save Gorbachev’s Stalinism. The Stasi, which had a spy for every 6.5 East Germans, could not save Honecker’s East Germany.

Suharto finally fell in Indonesia in 1998, without the military or his secret police lifting a finger. The same applied to Hosni Muburak’s regime in Egypt in 2011 (although the ‘deep state’ around the Egyptian military was able to appoint el-Sisi as President, when they felt the balance of forces swung their way).

The capacity for violence argument ASIO makes is completely dishonest. Writer and feminist Anne Summers was spied upon, even though her file had written in it ‘capacity for violence—nil’.

In 2005, ASIO organised the deportation of US antiwar activist Scott Parkin, who was, like refugees, assessed as a ‘threat to national security’. Then head of ASIO Paul O’Sullivan later admitted that Parkin had never been involved in any violent or dangerous protest activity, nor had he been convicted of any crime in the US.

While I somehow earned the label of honour for a ‘capacity for violence’ from two arrests in the 1980s – ‘Melbourne … members who have a history of physical violence are MB, PM and Tom Orsag’ – the labels are totally arbitrary. My file number has a ‘C’ added for that ‘capacity’. As do all those members listed, as well as the whole file for the International Socialists.

A British transplant – DG – appears in my file in 1989.

He impressed with his powerful and skilful oration. (Agent Comment: I do not know DG well enough to comment upon his propensity for violence. However, I believe he would have a capacity similar to JS, TO’L and MA in being able to rouse a crowd to violence if he so desired.)

So the agent doesn’t know DG ‘well enough’, but due to his ‘powerful and skilful oration’, believed he had ‘a capacity’. What a Kafkaesque world ASIO lives in.

Everyone who works for the police can be ordered to enact violence on people as part of their job. Yet that doesn’t seem odd to ASIO. To them, state violence is normal.

The Melbourne and Sydney offices of IS in the 1980s had their phones tapped, too. That meant all calls were recorded and where the call came from was recorded, also. As I travelled between both branches for a short while in 1984–85, I appear on both branch lists of attendees. As do my movements – either when I relayed them to someone, or when other people talked about them.

Every mention of your name gets you a new page in your ASIO file. But hey, who am I to tell them how to spend their time.

The IS offices themselves were bugged, which means that conversations between two people were taped. I found political chats with other comrades about various issues in my file. Most comments by other comrades and third parties about me were recorded, especially in my early days as a member. Most were kind and some not so, but those summing up my naivety were warranted.

The entrance to the offices also had cameras photographing people going into meetings. There may have even been hidden cameras, as files often featured a blacked out image of whoever was chairing the meeting. I got to chair a meeting back in the day. So that’s redacted, with my name underneath. This also happened to other people’s photos where my name appears as an attendee.

The mention of anyone’s phone number or address was recorded, as was anyone else’s mentioned in casual chit chat. So most times, agents knew where I lived.

ASIO also had a long-term informant in each branch, maybe more than one. You can tell because that person knew the names of most members and their aliases and they were noted. Informants would get a copy of the documents (from surveillance) and would then provide the full list of those who attended national conferences.

Back in the day, with branch committee minutes published and attendance noted, one’s name appears quite regularly alongside everyone else. Details were recorded if you called the office. If you called a person of interest for them, you might be recorded.

When the group was small, as it was when I joined, ASIO had tabs on every member already. You were walking into a surveillance zone.

Once you were a branch contact you are automatically added to their files. Once it is clear you have joined they go to mad lengths to establish your identity – full name, address, phone number.

My unusual surname caused them problems when it came to opening a file on me and they got it wrong in the first instance, before contacting the state car licencing body for my address, Telstra for my phone number, and the Australian Electoral Commission to confirm my address and who else lived in my house.

As the house I first lived in when I moved to Melbourne belonged to my maternal grandparents, this caused them all sorts of headaches. They eventually worked it out. My birth certificate was accessed for my mother’s maiden name. Obsessive.

As the group grew, the informer’s job became harder as more new people had to be identified, written up and described.

When the first Gulf War approached in 1991, the case officer made a list of possible violent people who could lead the masses. Such are their stupid fears.

ASIO’s whole history and record is one of illegal activity, such as break and enters, phone-tapping, and considering itself above the law. Its bias against the left is a product of its role as part of the state’s repressive apparatus.

This machinery of the police, military and the upper reaches of the public service bureaucracy are institutions for defending the local capitalist class against threats from mass social movements, workers’ struggles as well as foreign enemies and competitors.

ASIO’s unaccountable and secretive nature means it is able to operate as a law unto itself, even ignoring the wishes of governments, especially those of which it does not approve. Gough Whitlam and Jim Cairns were to find this out in 1972–75, when a group of hard-line ASIO officers plotted to discredit Whitlam in his dealings with ASIO’s then director general, Peter Barbour.

Because it is a part of a state that defends the capitalist system, ASIO shares the ruling class’s world view, values and methods. Many of its staff have been former military and police officers who brought with them values ingrained in their previous careers.

ASIO is a tool for the rich and powerful to maintain their control over society. It shouldn’t be trusted. Its history of right-wing bias, political interference and contempt for the requirements of the law show that the best thing we could do is disband it.

Lead image: from Tom Orsag’s ASIO file.