To have endometriosis is to lose your job, friends, partners, independence. To have endometriosis is debilitating – and can be just as severe as some of the illnesses already in the public consciousness (multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy). To have endometriosis is to lose hope in a future for yourself.

This is the narrative that has been missing since the July launch of Minister for Health Greg Hunt’s awareness campaign around this chronic reproductive condition. It might be one of the few redeeming policy packages to come out of the current government – a public health awareness campaign targeting workplaces, doctors and health professionals, and the general public. While the effort is admirable (and possibly several decades late), there’s a giant economic elephant in the room, which means we’re not painting a realistic picture of the disease.

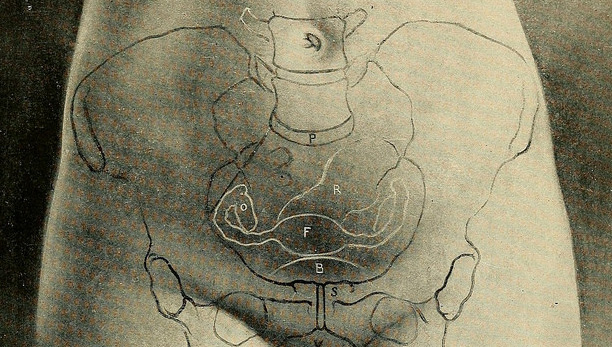

For those unaware, endometriosis is a condition where the tissue that is similar to the lining of the uterus occurs outside this layer. This can lead to endometrial growths forming not just on the uterus but on any organ in the body. These growths are benign but they can cause extreme levels of pain and they can stop organs from functioning altogether.

Endometriosis is incurable and, despite some claims, research shows that no existing form of treatment – including ablation/excision surgery, period-halting hormonal treatment or even hysterectomies – can guarantee that endometriosis won’t simply continue to form and grow.

In other words, there is no guaranteed effective treatment for endometriosis. While catching it earlier – the emphasis of the campaign – can make a difference in clarifying symptoms for sufferers, and some treatments may work for some, it’s no guarantee of a better quality of life.

So why did there need to be an awareness campaign? Presumably because many people will not have even heard of the disease, despite the current estimates that it affects one in ten women and over 700, 000 Australian women (probably quite a conservative estimate, given a long history of under-diagnosis).

On average, it is seven years before women are diagnosed with the illness. In part, this could be explained by the fact that the only current route to diagnosis is an invasive surgical procedure.

But the personal experiences of sufferers also points quite strongly to women not being believed or taken seriously by the medical industry.

I first went to a doctor at around age 19; my symptoms were presenting themselves as a UTI – except the UTI never went away. Ever, despite over 12 courses of antibiotics. I also had IBS-like symptoms; I went to GP after GP looking for literally any validation of these symptoms, which were increasingly making my day to day harder. At age 21, I gave up and fell into an extreme depression that made finishing my final year of university a living hell. By then, I simply assumed that I had quite literally been imagining my symptoms; that I was losing my mind.

Finally, at 26, after my symptoms had worsened significantly – I was experiencing painful cramping both during and outside of my periods almost daily – I stumbled upon endometriosis while googling.

After a few bouts of ending up doubled over in pain at work and having to rush to an ER at 5pm on the dot (because I knew over-the-counter painkillers were not going to cut it, and because I was still desperate for answers) and insisting to befuddled doctors that were examining me that I had endometriosis, I was eventually given a gynecological referral.

And even then I had to undergo expensive ultrasounds not covered by Medicare – which anyone on Centrelink would have been unable to afford – for doctors to consider a diagnostic laparascopy, the keyhole surgery for endometriosis. In between was the doubt and skepticism from doctors who were convinced that I had nothing wrong with me at all aside from a case of whinging too much about ‘normal pelvic pain’ (I would leave in tears).

Finally, a gynecologist signed off on the laparascopy, and I was diagnosed with Stage 4 Endometriosis (the final and worst stage of this disease).

What’s shocking is not my personal experience, but how unbelievably common it is.

Back to Hunt’s campaign.

While we can all appreciate the attraction of a celebrity face on an awareness campaign, it also shapes the way in which a disease is understood. Can you imagine, for example, Emma Watkins from the Wiggles talking about the pain a lot of women with endometriosis experience during penetrative sex on The Project?

For crying out loud: half of the celebrity faces in this campaign don’t even mention icky periods! And those who do portray the disease as a nuisance – the type of nuisance that only requires a few days off work a month!

Thus the problem is presented as merely one that requires negotiating something resembling period leave with a boss. While this would be an unbelievably progressive reform and a relief for many (and is already a legislative reform that has occurred in Italy, and is a policy here at Victorian Women’s Trust), the reality is far more grim and not one that wealthy women who own a children’s franchise can really capture.

There is an obvious contradiction in a Liberal government funding a campaign like this, when a good majority of women with endometriosis cannot work at all and spend many days a month bedridden and in pain. To make those facts part of the endometriosis conversation is to open up criticism of the government’s giant slashes to accepted Centrelink applications for the Disability Support Pension. Moreover, if even cancer patients are being rejected, how on earth do women with a disease that has been historically ignored or swept under the carpet – due to systemic sexism!! – have a remote chance of being taken seriously?

Where is the story about my friend, let’s call her Jessica, who after years of not being able to leave bed, of having to use the strongest painkillers available every single day, of losing money she saved from work and knowing she wouldn’t physically be able to endure something like Work for the Dole, walked into an ER and threatened the doctors with suicide if they didn’t perform a hysterectomy immediately? Jessica felt her life had become pointless – and that the federal government would rather see her on the streets than provide her with the support she truly needs.

I can’t imagine Mel Doyle faux-sympathetically groaning in agreement with that more unpalatable story on Channel Seven’s Breakfast.

But seriously, we need to stop running away from the inescapable fact that we cannot talk about any illness or disability without acknowledging the extreme poverty and materially uncertain conditions the Morrison government forces us to live in. We also need to stop hiding from acknowledging the structural sexism imbued within every aspect of the medical system.

Hunt’s promise of $2.5 million towards research into this disease does sound impressive – but it’s also the first serious research funding endometriosis has received in, well, ever. By comparison, far less serious problems such as research into male sexual performance are massively profitable areas with plenty of government investment. Only last year, the University of Sydney decided to tackle the starved-of-funding endometriosis by launching a study into the effect of endometriosis on men’s sex lives – that’s right, a disease that strips women of participation, agency and quality of life and which can make sex extremely painful only deserves funding because it might mean that men have less enjoyable sex.

Why are women so often ignored in the medical industry? Well, the answer goes back to the time-old question of productivity. Our mothers’ mothers were busy popping out child after child and while the nuclear family remains strong in informing the social reproduction of a society, women’s healthcare can be privatised at a micro-family level by the sheer reality that women were not the breadwinners and their lack of participation in the workforce made less of an economic dent.

Nowadays, a family cannot survive on a single income or at least this is significantly harder than several decades ago and we are having less children (by a long shot). To put it quite simply, when middle-class women who represent an important swathe of the current economy feel the brunt of endometriosis, so do our national productivity levels. These women raise their voices and are more likely to be heard, and, therefore, so are all women – but it’s important to make sure we get the story right.