Mental health care is in crisis in Australia. It would be almost impossible to find someone who didn’t hold that view. And there are, obviously, many organisations working hard to change that, including R U OK? Day, which happens to be today. Founded in 2009 by Gavin Larkin, after he lost his father to suicide, the organisation aims to promote awareness about depression and suicide – an admirable goal, and many people feel the campaign has helped them connect with a wider community.

But for some Australians, R U OK?’s approach is intrusive and damaging (something many mainstream newspapers as well as bloggers have commented on in, for example, 2010, 2013, 2015, several times in 2016, and in 2017).

Part of the problem is that R U OK? is not a service provider, but rather a public health promotion organisation and as such, they operate in an informal space. But as they have received over $2.7 million of taxpayer funding since 2011, I think they warrant further scrutiny. I had communications with Brendan Maher, the CEO of R U OK?, in the preparation of this article.

Susan: ‘I see the point in having RUOK. But modern society is all about asking so the asker feel better, not to actually help the askee.’

Victoria: ‘All she wanted to do was to make herself feel good by asking the question to someone – anyone would have done. On top of all the shit I was dealing with, I felt unworthy of help and like I was being used like a gimmick.’

Janet: ‘(I was) struggling with study in an online course … trying in vain to contact the tutor/ lecturer … get sent an email with instructions on how to support Ruok … nothing to say how can we help you. Kicker is it was a mental health course.’

R U OK?’s focus, according to its ‘policy and strategic context’, is to help the person asking ‘R U OK?’ to foster a sense of connectedness. If this leads to better outcomes for the person who isn’t OK, then that’s a good thing – but what happens when a superficial or ingenuous question with no follow-up leaves a person feeling worse?

While the organisation claims to foster a sense of belonging, it’s entirely possible that the welfare of those being asked – those who are not OK – is not improved by this question, especially when the asker may be ill-equipped to deal with an honest response.

Dave: ‘I understand the intention behind it but for me personally, the lead-up to and the day of RUOK Day is very difficult. It’s even harder if people know you have a mental disorder. It’s triggering and makes me even more hypervigilant, because I need to be on guard all the time because I don’t know if a random stranger or someone who knows me will ask me and I don’t know how to answer. RUOK Day is very intrusive for me and it puts a lot of pressure on people who are already very vulnerable.’

Claire: ‘(My daughter) said last day she felt singled out by the whole class (of Grade 9s) “checking in”. Then, because ASD, she didn’t have an appropriate response. She doesn’t lie. But she knew she was dealing with her shit – but didn’t need the intense interest or teasing.’

As the campaign only focuses on how to ask, R U OK? has no resources available about how to answer. September can be a difficult time for some people, braced to face an onslaught of questions about their medical history and private lives.

While R U OK? promotes asking genuine questions in an appropriate context and workplaces being sincere in their R U OK? Day festivities, there are many anecdotes about times processes haven’t been followed, and when there is no back-up plan. In such situations, vulnerable people are left to defend their personal and medical privacy for themselves, without support from a campaign (that compromised their privacy in the first place).

Linda: ‘I agree that it’s a great initiative but it has no substance behind it, which can make an asking so much more dangerous.’

Stella: ‘I have my own loooonnnnggggg story. Basically I’ve learned to just rely on myself. For people to say “ask someone for help”, “get a babysitter”, “ask a parent if they can take your kid to sport” is a mild trigger for me.’

Anita: ‘A few years ago when I was not ok, I skipped tafe on RUOK day because they were basically having a big party – balloons and a bbq and live music, and I knew I would cry if someone asked me if I was ok. It definitely made me feel isolated at the time.’

On 13 September, broadcast and social media will be a sea of R U OK? advertising, and our workplaces and educational institutions will be full of yellow balloons and cupcakes. The day is ‘pretty hard to miss’, but this forces people who can’t cope with the question to withdraw further.

When a mental health advocacy day causes people’s mental health to be negatively impacted or encourages people experiencing depression to isolate themselves, then something is clearly wrong. With R U OK? Day’s focus on the person asking the question not the people being asked, the organisation appears to have missed the mark.

Carmel: ‘In my case, on the odd occasion that I actually told my story to someone, they were so overwhelmed they couldn’t cope and didn’t want to be near me anymore. Best thing to do on RUOK day is say yep I’m fine and then cry in a corner.’

Victoria: ‘Firstly, even though the premise of checking in with people is a good one, it’s not much use asking someone if they’re ok if you don’t have the capacity to deal with the someone answering “no I am not”.’

Jezebel: ‘I don’t want someone I don’t like or know well asking me cos I doubt I will keep my cool. I’m already getting hassled to make sure I wear yellow on the day.’

R U OK? distributes information about how to respond when the answer is ‘no, I’m not ok’ and Maher claims that the ‘How to ask’ page is the most frequented on their website. Its advice about how to have a conversation when someone who isn’t OK includes information on how to prepare for and navigate a meaningful conversation, all of which is good advice, but it’s miles removed from a staffroom party with yellow balloons.

Where is the information on what to do if the response is more complex or severe? The website urges people to ‘check in’ if the person has been ‘not OK’ for more than two weeks, but doesn’t include informtaiton on how to manage a conversation with a person who has been ‘not OK’ for more than two months, two years or two decades. While early, peer-to-peer intervention is the focus, R U OK? doesn’t have any resources available to assist when it is long past early intervention.

I asked ‘Which of your resources give the person asking skills to manage if the answer is more than just “No, I’m not ok”, but “No, I’m not ok and I can’t afford to see any psychologist until January next year” or “No, I’m not ok and my mental illness has been classified by my psychiatrist as treatment resistant” or any other number of serious and ongoing responses which referral to a helpline or GP is woefully insufficient to support?’ Maher responded, ‘This is not a question I can answer.’

Of course, anecdotes are not a reliable indicator of the overall impact of any campaign; for that, robust statistics are required. According to R U OK’s post campaign evaluation, its negative feedback is very low – but this claim needs to be interpreted with caution.

First, because the statistic is from their own online survey. Of the possible 61 questions on the survey, only 9 of them specifically ask about the respondent’s experience of being asked about being OK. While the analysis did note that the number of people who said they answered ‘yes’ when the answer really was ‘no’ had decreased from previous years, the numbers themselves were too small to be statistically significant. It’s also likely that people who had had negative experiences of R U OK? Day would choose not to fill out a survey largely focused on the benefits of the campaign.

R U OK? Day’s media sentiment report similarly claims very low instances of negative feedback, but does not differentiate or comment on if the media was focused on the asker, the respondent, the brand, events or other topics so this is also not a reliable indicator of the overall effect the day has on those who are not OK. The campaign does not collect statistical information on social media or comments on online news articles, so experiences of those being asked aren’t captured in a comprehensive and reliable way there, either. None of the anecdotes quoted here, or relevant tweet threads, are included in this data, and the organisation doesn’t actively seek them. The breakdown of feedback about R U OK? Day on social media is simply unknown.

Both the campaign evaluation and the media report claim high numbers of people who have positive experiences of the campaign. Reducing the stigma of mental illness and suicide and fostering community are worthy goals. But an accurate understanding of why being asked ‘R U OK?’ might be distressing is critically needed.

R U OK? have involved many experts from leading mental health institutions and cite evidence-based strategies and resources for help givers; it is reassuring that there is a sound, professional basis for their resources and campaigns. The organization also monitors its social media accounts (by R U OK? during the business hours and by Lifeline after hours) and adheres to Everymind’s Mindframe guidelines about the responsible portrayal of suicide. The organisation also counters much of the criticism that they receive, suggesting, for example, that people should ask every day and in a genuine way, with their own resources.

Clearly Australians need all the help we can get when it comes to mental health support. For many people, a heartfelt, meaningful conversation or a few sessions with a counsellor might be enough to help them get OK. But let’s be real: you can’t have a meaningful conversation when your privacy is under the microscope at a yellow-themed office shindig.

We need to rethink the hype, and prepare ourselves with adequate responses for those who are not OK.

(Note: all anecdotes are shared with permission and have been assigned pseudonyms. If you’re feeling distressed, please consider contacting a health professional, trusted friend or family member, or Lifeline on 131 114 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 46 36. If life threatening, please call 000 or the emergency number in your country if you are reading this from outside Australia.)

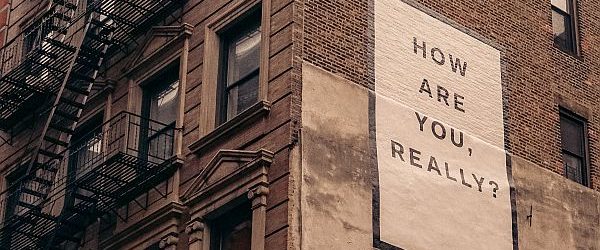

Image: Newtown graffiti / flickr