A recent UN Committee on gender inequality examined Australia’s implementation of the primary convention of women’s rights and gender equality. As covered in The Feed, the Committee reported that it was ‘extremely concerned by cuts to women’s shelter services, financial and legal services.’ Committee expert Nahla Haidar noted: ‘continuing to cut is obviously going to create more vulnerability.’

In 2016, the Federal Liberal Government announced plans to cut $35 million in funding to community legal services for victims of domestic violence over a three-year period. In 2017, it was reported that the federal government was also planning to cut $110 million in funding to women’s refuges. Amanda Keeling noted for the Women’s Electoral Lobby that the 2018-2019 Federal Budget was ‘an opportunity to provide refuges with funding certainty and reduce the number of women and children living with violence. But there was nothing for those housing services in the Budget, and more women’s lives are at risk as a result of Government inaction.’

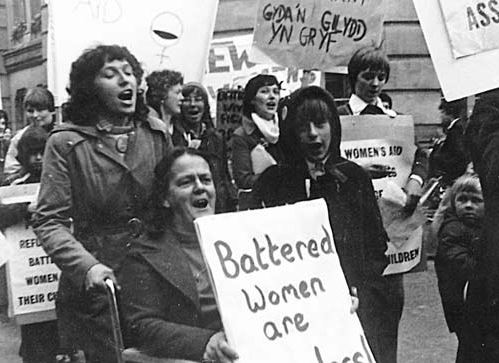

In On for young and old: Australian Intergenerational Radical Lesbian Feminist Anthology, Radda Jordan writes, ‘we now take for granted that domestic and family violence is on the national agenda.’ Feminists of the Women’s Liberation Movement fought to create and maintain the first women’s refuge in Melbourne, known as Halfway House, between 1974 and 1976. The story of Halfway House’s fight for funding shows the importance of the role of contemporary women’s refuges and of their need for federal funding.

The first women’s refuge in Melbourne opened in 1974. According to the Women’s Liberation Halfway House Collective (WLHHC), in Herstory of the Halfway House, 1974-1976, ‘the need for a Half-way [sic] House had been discussed for a long time in the Women’s Liberation Movement’, as the Women’s Liberation Centre ‘constantly received calls from women needing somewhere to stay for awhile, often in desperate circumstances.’ In April 1974, a meeting was called to ‘discuss the setting up of a halfway house… a halfway point for women between their old lives and new ones.’ Ultimately, the women’s Halfway House would provide short-term accommodation to women and their children.

In the beginning, the WLHHC sent ‘hundreds of letters… to groups and individuals both within and outside the Women’s movement’ in an attempt to find a house that would serve as a suitable refuge. On 12 August 1974, an anonymous woman offered the WLHHC her house in Kew for twelve months. Due to hassles from neighbours, some members of the local council and ‘friction with the owner,’ in 1975 the WLHHC moved from Kew into a house in Ormond. The lease for the Ormond house was short however, and by the end of 1975, the WLHHC had leased a house in Fitzroy.

Jean Taylor notes in Brazen Hussies: A herstory of radical activism in the Women’s Liberation Movement in Victoria 1970-1979, that ‘over the past thirty years… Halfway House changed location several times.’ Throughout their thirty years of operation, Halfway House has received financial donations from personal acquaintances and women from the Women’s Liberation Movement, to unions and other political groups. Publicity has also encouraged the general public to donate.

Not long after the WLHHC established the Kew house as a refuge, the WLHHC realised that they would not be able to operate on donations alone. Not only did they need money for the upkeep and maintenance of the house, but the Collective also lent money to its residents for ‘bonds and other accommodations outside the Halfway House.’ According the WLHHC, women struggled to find suitable accommodation as the ‘only money most women had was their pension cheques’ and these rarely seemed to arrive on time. During this time, the WLHHC drew up a proposal to ask for $100,000 to go towards ‘buying a suitable house and to cover maintenance and basic running costs for the first year.’ The Collective proposal also requested ‘$15,000 to cover salaries, office expenses and overheads.’ Up until this point, all of the women who contributed to Halfway House were volunteers. The proposal was sent to numerous government departments.

In an attempt to highlight the need for government action, the WLHHC reached out to the press. They also refused to accept women who were referred to them by any government agency, in an attempt to ‘pressure the Government to recognise its responsibility to homeless women and children.’

In February 1975, it was announced that the WLHHC would receive an interim grant of $14,600 from the Hospitals and Health Services Commission. However, according to the WLHHC, the State Health Department viewed the women with ‘suspicion, if not downright hostility.’ The State Health Department ‘held up’ the money. By May, the WLHHC had run into debt, as they had been ‘spending money on the basis of the promised grant.’ The women planned to organise a demonstration in front of the Victorian Health Department to protest the red tape and bungling. However, before they could demonstrate, two thirds of their total grant was provided, on 28 May 1975.

Due to their first grant being interim, the WLHHC prepared more submissions for funding and met with the Homeless Persons Assistance Program. After consulting other women’s refuges and ‘lengthy discussions,’ the WLHHC decided to join the National Confederation in September 1975, as they offered the WLHHC ‘some protection against further hassles with the Victorian Health Department.’

The next amount of funding came from the Community Health Program in October 1975. $51,098 was given to the WLHHC for the 1975-1976 financial year. However, this was ‘less than half’ of what they had requested. The money from the funding went towards rent, salaries, running and maintenance costs and capital costs. There were some aspects State Health Department would not fund, one of which was ‘anything to do specifically with children.’ The WLHHC sent numerous submissions to cover the cost of looking after children. In March 1976, the Children’s Commission had announced that the Halfway House would receive a grant of $5,123, ‘to be spent mainly on the salary of a child care worker.’

The funding that the Halfway House received from the government was inadequate in covering the costs of the refuge. According to the figures provided by WLHHC, between 1974-1976, 907 women and 1949 children had made requests for accommodations. Only 202 women and 304 children were approved for temporary accommodation at Halfway House. Thirty-eight women and fifty-two children were provided temporary accommodation in the private homes of the WLHHC. 667 women and 1593 children were unable to receive help from the Halfway House due to inadequate funding, attempts to avoid overcrowding, and because they had been referred by government agencies.

In considering the inadequate funding allocated to Halfway House in 1974-1976, and the $35 million and $110 million cuts to women’s and community services in 2016 and 2017 respectively, it seems that little has changed in the government’s attitude towards funding women’s refuges in the last forty years. While the 2018-2019 Budget itself did not provide any relief to women’s refuge and women’s homelessness, the Liberal Government promised to set aside funding for ‘women’s economic security to be delivered in September.’ But we have to do more than just hope that this promise will mean that women’s refuges will receive better funding. We need to make our voices heard.

Women who have experienced domestic abuse are often asked why they did not leave sooner. But if government does not take responsibility for funding safe places for women and children escaping domestic violence, then what opportunities has it provided to some of our most vulnerable members of the community?

If you feel strongly about this issue and want to help, the Women’s Liberation Halfway House is still in operation and they continue to accept donations. The YWCA’s housing program also provides housing to vulnerable women and children in Melbourne and Geelong. The YWCA accepts donations and memberships, and they also provide the opportunity to volunteer.

Image: Women’s Liberation