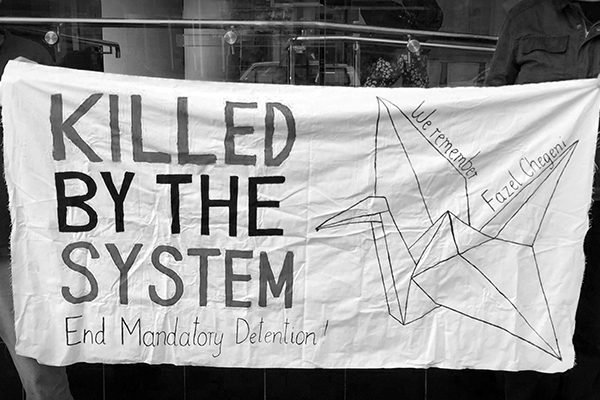

Over the last month, the Deathscapes project, for which both authors work as Chief Investigators, has produced daily dispatches from two successive inquests into racialised deaths in custody. The first of these was into the death in custody of 26-year-old Dunghutti man David Dungay, in Long Bay gaol, held in Sydney from 16-27 July. The second, held in Perth from 30 July-10 August, investigated the death of the Kurdish refugee Fazel Chegeni Nejad, aged 34, held in custody at the North West Point Immigration Detention Centre on Christmas Island.

Both inquests were enabled by a recommendation of the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody:

That all deaths in custody be required by law to be the subject of a coronial inquiry which culminates in a formal inquest conducted by a Coroner into the circumstances of the death. Unless there are compelling reasons to justify a different approach the inquest should be conducted in public hearings. A full record of the evidence should be taken at the inquest and retained.

The establishment of the Royal Commission and the release of its recommendations are considered a turning point for justice in Australia. The requirement that a coronial inquest be held, in public view, and that a full record of evidence be taken and retained for the future were key measures calculated to establish principles of accountability and transparency on the part of the law – specifically to Aboriginal families and communities, but also to the communities and families of all who die in custody.

Despite the promise of justice held out by the prospect of a public inquest, glaring disjunctions persist between these uncompromising principles of accountability and transparency and the daily experiences of families and communities, as they observe the proceedings of a coronial inquest or gather outside court with their symbols of mourning, protest and resistance. These disjunctions are at the heart of the recent television series Seven Seconds, which explores the death of an African teenager at the hands of a white policeman, set against the backdrop of Black Lives Matter activism on the streets of New Jersey. On his recent visit to Sydney, Hawk Newsome of Black Lives Matter pointed to the similarities between Eric Garner’s death on the streets of New York and David Dungay’s death in Long Bay, signalling the global relevance and reach of the BLM movement.

Following Newsome’s visit, and concurrent with Deathscapes’ dispatches from the inquests, we found ourselves closely watching Seven Seconds, whose strongest effects are a series of visual juxtapositions between the interior of courtrooms and police stations and the surging upheaval of demonstrators on the street outside; between the lives of families brought to breaking point by the death of a child, and a legal apparatus that is not merely indifferent, but infrastructurally inimical to them.

Hawk Newsome, a leader of Black Lives Matter, at the David Dungay rally outside the Downing Court Centre / Joseph Pugliese

Our daily dispatches, which evolved organically from our experiences of the courtroom, are intended to explore the inquest as an event that far exceeds the text of the coronial findings published at the end of proceedings. An inquest’s actors include not only its legal protagonists, but a cast that includes family members, supporters, protesters, bystanders and so on. As a public event, with its prescribed protocols, scripts, props and rituals, the inquest performs the ceremony of justice. As pointed out in the dispatches, in the case of Mr Dungay’s inquest, it presented an object lesson for his family in the justice of the settler state:

From day one of the inquest, the extended Dungay family has been in attendance in court with their children. There is one baby and a number of children and teenagers. They sit together or with family members. When the traumatic video of the death of Mr Dungay is shown – it has been shown every day of the inquiry thus far and it never gets easier to watch – different family members and supporters take the children out of the courtroom. They can be seen playing either in the foyer or downstairs on the large covered verandah of the Downing Court Centre. As the witness testimonies unfold, I reflect on the strong kinship bonds that bind the extended Dungay family and the care and love they show each other in this painful setting. I’m also compelled to dwell on the strength and maturity of these children. They are here in this court cutting their teeth on the infrastructural racist violence of the settler state and on its fatal and ongoing effects on Australia’s Indigenous people. They are here learning of the dangers they risk facing as they grow into adults. They are here, in a court of law, absorbing and building up their store of resilience and love in order to survive, defy and flourish despite the transgenerational trauma they experience in their everyday lives… Unintentionally, and well beyond its strictly judicial brief, this court of law of the settler state offers them yet another object lesson for their future.

David Dungay Dispatch Day 4, 19 July, 2018

In this article, written in the days immediately following the inquests, we explore the object lessons offered by the inquests for Mr Dungay and Mr Chegeni Nejad. We detail the routine operations of epistemic violence, and the disjunctions between the process and its violent and troubling effects, that became evident to us on several levels.

Infrastructural Processes and Epistemic Violence

The epistemic violence of the inquest takes place three levels. Firstly, the mundane, near imperceptible level of routine interactions; the daily indignities and racialised microaggressions that make up the everyday etiquette of the courtroom. Recently, an observer at the inquest for Ms Dhu remembered how court officials assiduously provided tissues for police witnesses, while the all-too-evident distress of family members received no such solicitous attention. On the contrary, family and supporters were subjected to frequent disciplining and made to feel as if they had no place in the courtroom. In the case of the inquest for Mr Chegeni Nejad (coincidentally held in the same courtroom of Perth Central Court as that for Ms Dhu), the three contributors to the Deathscapes dispatches were singled out and called outside the courtroom to have suppression orders personally pointed out to them, thus preemptively casting us as intending lawbreakers and interlopers who could be instantly identified.

Secondly, the insidious processes of smearing and discrediting of the victim that begins almost immediately following a racialised death at the hands of the state. In Seven Seconds, the teenager killed in the hit and run by a police officer is immediately subjected to allegations of drug dealing and gang membership. Similarly, in the inquest for Mr Chegeni Nejad, terms such as ‘drug seeking’, ‘alcoholic’ and ‘HIV’ were frequently used by Counsel for International Health and Medical Services [IHMS] and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection [DIBP], although there is little warrant for them in the available documentation. Neither were these damaging insinuations contextualised against the proven history of torture experienced by Mr Chegeni Nejad, and the possibility that he might have sought to alleviate the symptoms of consequent post-traumatic stress disorder.

Activist Pamela Curr, who knew Mr Chegeni Nejad during his period in Melbourne, remembered him very differently from the man described by IHMS and DIBP Consul. She commented, ‘We knew Fazel as a gentle, quiet man who couldn’t understand why he was still in detention because he was found to be a refugee. All he wanted was freedom and peace. He was in the community for eight months; during this time he spent his days helping others, riding his bike and looking after his friend’s dog’ (quoted in Fazel Chegeni Nejad Dispatch Day 10, August 10, 2018).

Vigil for Fazel at Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation (MITA), 2015

In marked contrast to the strong presence of a network of family, kin and supporters at the inquests for Mr Dungay or Ms Dhu, inquests for refugees and asylum seekers are inevitably lonely, starkly clinical events, far away from family. Fellow-detainees or asylum seekers and refugees in the community face a number of constraints in attending court. Curr, the only one present who had known Mr Chegeni Nejad during his life, commented on her shock at how ‘silenced and extinguished he was’ in the process of the inquest.

Day after day, the Deathscapes team wore small folded paper cranes to remember something of this extinguished Fazel, a gentle man who had made origami cranes to distribute to people in hospitals and care homes. Like the Dhungutti artworks the Dungay family displayed outside the courtroom, the cranes sought to bring into the inquest all that is not simply excluded, but denied, by the legal frame. The cranes represented Fazel Chegeni Nejad’s hopes of freedom, invoking the traditional Japanese belief that one who folded a thousand cranes would eventually achieve a single wish. Like his attempt to climb onto rooftops to experience a sense of freedom, the crane stood for Fazel’s hope of soaring above the razor wire and electrified fences that had confined him in various forms of detention for over four years.

Paper crane worn in court on Day 6 of Fazel Chegeni Nejad’s Coronial Inquest / Michelle Bui

The third level of disjunction we want to mark is that between the emotional truths and embodied knowledges of families and communities and the knowledge permitted within the purview of the law and the inquisitorial frame. As described in one of the dispatches:

In his evidence, one of the officers says that Mr Dungay was ‘trying to trick the officers’ through his repeated cries of ‘I can’t breathe.’ At this, members of the Dungay family rupture the ritualised white decorum of the court with a burst of heartfelt expletives. The expletives work to expose and mark what the family perceive to be the lies of the settler state’s carceral operatives. Each perceived lie is punctuated with the eruption of expletives. Throughout the course of the inquiry, these disruptive expletives become one way to mark the family’s unmediated agency: raw, angry and impassioned, they bespeak long histories of Indigenous refusal and speaking back to a racialised criminal justice system that rarely delivers justice to those who have died in custody or to their families.

David Dungay Dispatch Day 2, 17 July, 2018

These suppressed emotional truths of families and communities at the limits of the state trouble its confident declarations; they seep, disguised or barely acknowledged, into popular consciousness, to emerge in productions like Seven Seconds. In a key scene of the series, the police officer accused of the killing testifies about being so captivated by a sudden glimpse of the Statue of Liberty that he did not see the wounded body of the young boy before him. Critics have been quick to condemn the symbolism here as heavy-handed, but for director Veena Sud the statue embodies a fundamental truth about racial inequality in the United States: ‘The American dream was being extended to the immigrants of Europe but not to the black and brown citizens, many immigrants themselves, of this city, this country.’

Despite its at-times clichéd characterisations and plot lines, Seven Seconds offers no comforting narrative of a system that, despite all the odds, delivers justice for the family of a young black boy killed at the hands of a police officer. Rather, true to the real-life stories of Oscar Grant, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Amadou Diallo, LaTanya Haggerty and so many others, the series represents the unrelenting blockage of justice at every turn. It shows the powerful alliances within the criminal legal system (the unspoken fraternity of lawyers, judges, magistrates, police and prison officials) that conspire to deny the possibility of justice for the dead and the devastating, but unspectacular and continuing, consequences of that denial on black lives. The series, perhaps unsurprisingly, was cancelled after its first season.

For us in Australia, the disjunctions that unfolded in the course of these inquests brought into acute focus what we would term the deep levels of epistemic violence that are embedded in law and that are, precisely because of their infrastructural nature, largely invisible to law’s operatives – the lawyers, coroners, court clerks and so on – even as they are palpably visible to those officially ‘outside’ its formal circuits. Indeed, we were compelled to reflect on how often the most graphic instantiations of law’s epistemic violence were reproduced in its seemingly most routine practices and procedures. For example, in the multiple screenings, day after day, of the video footage showing Mr Dungay dying in the process of his violent transferral by the Immediate Action Team from one cell to another.

The forensic analysis of this video, that literally captures the last desperate breaths of young man before he collapses due to cardiac arrest caused by positional asphyxia, was detached and abstracted from the embodied violence it evidenced. The repeated screenings and the attendant forensic analyses became, for the family, yet another form of trauma they were compelled to endure. Here, routine legal procedure amplifies the effects of epistemic violence.

Statement read by David’s mother, Leetona Dungay / Joseph Pugliese

In the course of Mr Chegeni Nejad’s inquest, we reflected on yet another form of law’s epistemic violence, as his fellow inmates, some still in detention, were called to testify:

The detainees who testified today were determined and compassionate men who showed the same care for Mr Chegeni Nejad that he had demonstrated for his friend four years ago as they both embarked for Australia with hope in their hearts. The witnesses’ care was evident in their coming forward to give evidence despite potential personal consequences, and in the face of the shoddy obstacles posed by a legal machinery that remains deeply monolingual. For example, witnesses who gave their original verbal testimonies in their own languages received written transcripts in English just prior to the inquest – making it impossible for those who did not read English to refresh their memories of what had happened in 2015. Their difficulties were compounded by at times inadequate interpreting, by technological failures and by counsel who appeared unfamiliar with the basic protocols of interpreting. Some of the misunderstandings that transpired were received with titters by the legal bigwigs, but for others present they represented one more link in the chain of indignities we inflict on detainees.

Chegeni Nejad Dispatch Day 6, August 4, 2018

The erasure of linguistic difference, the presumption of universal literacy in English, the failure to provide adequate translating and interpreting services, and the legal fraternity’s sense that the ensuing linguistic misunderstandings were cause for amusement – all these factors exemplify the operations of epistemic violence in the course of law’s routine operations in the space of the courtroom. These different forms of the law’s violence, which underscore its otherwise unmarked raciality, must be seen as producing diverse forms of injustice and violence.

Clearly, not everyone is equal before the law when English, for example, is not the first language of a witness called to give evidence. Clearly, not everyone is equal before the law when some witnesses’ testimonies are potentially compromised by the court’s failure to supply adequate transcripts in their own languages. Clearly, not everyone is conferred the same level of dignity and respect within the court of law when, due to court’s own linguistic failings, the non-native speakers’ linguistic indignities are seen as little more than the stuff of comedy. Law’s epistemic violence, in such instances, is generative of epistemic injustice.

Reflecting on the many disjunctions and deferrals of justice we had witnessed at the two inquests, we remembered the inspiring words of Helen Ulli Corbett, a foundational figure of the movement to end Aboriginal deaths in custody, at the beginning of the Royal Commission:

The history of the national campaign demanding a Federal Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody was coordinated by Aboriginal/Islander families who had a relative die in prison or police custody or their supporters. They are a living testimony of what united strength is all about. The Royal Commission is one of the most recent and greatest achievements of our people. We have turned the tables! Both internationally and nationally we are putting European law up on public trial. It is now forced into explaining why our justice system allows so many of our people to die in their prisons and lock ups.

Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia Annual Report, 1987-1988

Almost thirty years later, the promise of putting settler law up on trial remains to be fulfilled by the accountability mechanism of the inquest. In the breech are the myriad forms through which marginalised groups seek to articulate their counter-understandings and painful lived knowledges of the law. Veena Sud commented on the significance of Seven Seconds:

I felt desperate to tell this story … It’s about time to hear people of color and women telling stories that speak to our experience, or close to our experience. We know these stories. The truth of them is ours to tell.

How do those for whom the law holds out little promise of justice, and on whom it inflicts further violence in the course of processes supposed to elicit the truth, tell the truth outside the law’s shadow, the truths that are theirs to tell?

Lizzy Jarrett, Auntie Deborah Campell, Leetona Dungay, Cynthia Dungay, Lisa Deluca and Simone Pash outside Downing Centre Court / Joseph Pugliese

Postscript

The coronial inquest into the death in custody of another Indigenous man has recently commenced in Adelaide. On 26 September 2016, Wayne Fella Morrison died after being violently restrained by correctional officers while on remand in a South Australian gaol. Morrison had no criminal convictions and it was his first time in custody.

In the course of the inquest so far, shocking video footage has been shown of the lethal practices of restraint deployed in the transfer of Mr Morrison from the gaol to the prison van. The footage stands as a virtual repetition of the David Dungay forensic video. At one point, the video shows Mr Morrison crushed under the weight of fourteen correctional officers: it is impossible to see his body under this seething scrum of officers. It is obvious that Mr Morrison, handcuffed, restrained in a prone position and placed under the oppressive weight of so many officers, just as Mr Dungay was, could not possibly breathe. By the time Mr Morrison was transferred to G Division in the gaol, a journey that took three minutes, he ‘was found to be blue and unresponsive’. Just as in Mr Dungay’s case, panicked attempts to resuscitate him failed.

Mr Morrison’s sister, Latoya Aroha Rule, spoke to the violent death of her brother while in custody: ‘It was distressing to witness the footage today of the final moments of my brother’s time on remand and to count the number of correctional officers involved in his restraint and in the transport van. It also saddens me to know he was wearing a spithood at the time of his death – similar to that shown in the restraint of Dylan Voller in images that shocked Australia [from Don Dale prison in Darwin].’

Dylan Voller attended the Mr Dungay inquest as a way of marking his support for the family and he spoke of David Dungay as being, in Indigenous culture, his brother.

The death in custody of Wayne Fella Morrison, 29-years old, occurred less than a year after that of David Dungay. Both deaths evidence lethal practices of structural repetition in the correctional management of Indigenous inmates. Both deaths bring into focus the serial nature of the violence deployed against Indigenous prisoners across Australian states. These two deaths, caught in the forensic medium of CCTV footage, stand as mirror images to each other. They bear testimony to violent truths that continue to remain unaddressed by Australia’s criminal-justice system.

Header image: Demonstrators highlight systemic issues outside coroner’s court / Michelle Bui