When Pound structured poetry into three forms (melapoeia, phanopoiea and logopoeia) in the 1930s, it’s unlikely he could have anticipated the confessional, tag-and-shareable, anti-intellectual iteration of online poetry in the 21st century. #instapoetry, Pinterest poetry and Tumblr poetry, often created by the same individuals and shared across platforms, do not lure audiences through the phonology and musicality of their choice of words (melapoeia), nor do they work to throw images upon the ‘visual imagination’ (phanopoiea). They certainly cannot be said to practice logopoeia, the vehicle of obscure metaphor and ‘dancing intellect’. Rather, these poems push a direct, targeted meaning which is arguably without poetic or intellectual interference.

What’s most notable about these contemporary poems is that they’re hugely, unprecedentedly, absurdly popular. If anyone told me ten years ago that a female poet would sell over three million copies of her debut collection, or that the same poet would reach the Amazon top three best seller list with the follow-up, I’d have scoffed right onto their copy of Eat, Pray, Love (later choking back tears, scrounging my last ten dollars to buy cheap wine). This has, nevertheless, become the reality of celebrity popular poetry in this decade – if you’re young and inspiring and beautiful enough.

If you didn’t already realise, I’ve been talking here about the Taylor Swift of poetry, Rupi Kaur, who inspired an audience of more than 700 to shake it off at a reading in Toronto in 2016, while Pulitzer Prize winner Junot Díaz read in another corner of the same library to a much smaller audience. Perhaps that had something to do with his power-abusing predatory behaviour towards women; regardless, the movement away from traditional poetry towards a more accessible, openly emotional style (dominated by female-identifying or gender diverse writers) signals a major trend that is worth taking a closer look at.

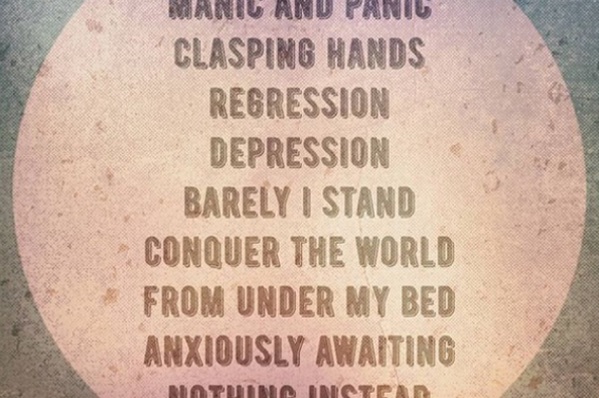

So what do these poems look like? How do we identify them? For starters, they’re defined by where they are found – on social media. And all of the usual requirements for a successful social media post apply – they must be snappy, able to be appreciated at one glance. They must be visually attention grabbing. Above all, the content must address the shared experiences and emotions of humanity in order to be shared digitally between users and across platforms – and it must do so quickly enough not to lose the interest of the devoted scroller.

This results in poems up to about sonnet length, but usually of only around four to six short lines with frequent line breaks. The enjambment is so prevalent that most poems could easily, when stretched out, be simply a statement sentence or affirmation. ‘What never was / what could have been, / was more to me / than anything else’, posts award-winning instapoet and novelist Lang Laev. Laev boasts over two million social followers. Erin Hanson, an early 20s Australian instapoet, is unavoidable if you type ‘Australian poetry’ into the Pinterest or Instagram search bars. Her work is full of simple rhyming couplets, obvious imagery and gentle themes.

Kaur’s works, as well as those of a number of her contemporaries’, are illustrated with line drawings which arguably guide any possible interpretations of the work. Mixed media works which combine text and image can function in three ways: the image can work as a straightforward visual illustration of the textual content; the text can operate as a descriptor of the image (captioning, for example); or the two can work in a symbiosis to create a new meaning which would not exist if they two media were separated. These works seem largely to fit into the first category, and at their most successful, verge into the third as presenting a combined entity.

It’s no surprise that instapoets are using mixed media to get the message across. (This isn’t the first time a group of writers has taken to mixed media work in order to grasp at the representation of strong emotions. Robert Essick describes the difficulty writers experience when struggling with the use of traditional media to convey meaning, using the term ‘representational anxiety’.) The form itself suggests the visual – a square digital canvas where layout, typeface and design are vital to draw the eye in an over-saturated forum of sharing and distributing. Before the content is even read, the audience needs a moment of recognition that this is *a poem*, that it will share or illuminate something.

Many posters use typewriter text to signal their presence and advertise a vintage literary aesthetic in a digital age. Rather than being intended for a monograph book format, these works are made to be shared on Pinterest, Instagram, Facebook timelines, or, in the increasingly shrinking real world, printed and exhibited as a personal statement of identity on an office cubicle pin board. Most people have had a ‘Word Porn’ image flit across their timeline, crying out unattributed literary melancholy or personal affirmation to the world. Aligning this sort of work with pornography just works to highlight its single-purpose, gratifying nature.

In the few years since #instapoetry has boomed, these works have replaced ‘Hang in there baby’ style motivational posters as the most popular way to signal personal strength and affirmation and to curate a public persona online. Sharers are most commonly female millennials, who according to studies experience high rates of anxiety and depression, especially those who identify as lonely. They’re also highly tech-savvy – most millennials would have been given or have bought their first mobile phone in high school, and followed the development of browser-based social media from ICQ and Myspace to phone apps like Snapchat and Telegram. Time is money, and most millennials simply don’t have the free time to pursue vigorous reading outside of long work hours and study commitments, socialising and the far more readily accessible entertainment options of Netflix or idle phone scrolling. Anything that fits onto a phone screen, and can be taken in without too much attention or commitment, is at a premium.

In my research for a 2017 ASAL conference paper on this topic, I briefly spoke with an #instapoetry fan to get some insight into why these works are so compelling. Carina is thirty-one years old, university-educated, multilingual and classically well read. She’s a big Rupi Kaur fan, and feels that the latter’s book Milk and Honey helped her through a particularly tough time in her life.

‘I guess the reason I respond to them so well is that her words often perfectly capture and encapsulate feelings I’ve had myself,’ she tells me. ‘They are simple, artless, accessible. They aren’t pretentious or trying to be clever, they are just thoughts, but distilled and presented with a clarity that makes them incredibly attractive to me in the chaos of my life right now.’

‘The “gold’” one actually made me cry,’ she says, ‘because it is so simple, so clear, it encapsulates a moment of compassion and insight that in my current experience of pain and “feeling lost” felt very touching and real.’

Carina believes the popularity of the style comes down to accessibility. ‘I don’t have to think too hard. It’s there, it speaks to me openly and clearly,’ she clarifies. ‘It speaks the words I need to hear… The words I wish I had said or written. Her poems are an extension of my voice, or what I would like my voice to sound like. As much as I adore Shakespeare’s sonnets or Dickinson’s tortured genius, they are obfuscated, they require effort and attention to decode. Sometimes it just feels good to be heard and understood.’

This level of trust and emotional connectedness to a writer or work can be risky, though. While Kaur’s work delves into female trauma (emotional abuse, menstruation, rape and other commonly avoided ‘hard’ topics come up in her work frequently), a number of other poets skirt around real issues and instead address easier shared emotions and experiences – breakups, loneliness, self-doubt – almost exclusively from a female perspective, despite a number of male writers entering the fold.

‘Just enough / madness / to make her / interesting’, writes conspicuously male instapoet Atticus, who keeps a secret identity and wears a mask at his readings. Atticus writes about women’s feelings far more frequently then he writes about men or himself: ‘She was afraid of heights / but she was / much more afraid / of never flying.’ Another male instapoet, r.H. Sin, similarly treads the waters of female emotion with confidence. Sin describes himself as a feminist. His book She Felt Like Feeling Nothing is described on Amazon as ‘a safe space where women can rest their weary hearts and focus on themselves,’ a ‘poetic reminder of women’s strength.’ The description also steers clear of indicating that the poet is male.

A cynic might suggest that a particularly vulnerable female audience is being exploited by male writers using emotional manipulation and tropes to appeal to, and profit from, shared female experiences of which they have no first hand knowledge. Or perhaps they’re genuine.

Certainly instapoet ‘Tyler’ isn’t being genuine – better known as Thom Young, the prize-winning Texan poet noticed the boom in online sharing of ‘short, trite poetry’ and started an experiment, writing his own version of this ‘pop poetry’, accordingly seeing his social-media following skyrocket.

It’s clear that this poetry follows a formula and constitutes its own poetic subgenre. Currently, we appear to agree to call it #instapoetry (which conveniently both reference the medium – Instagram, though not exclusively – and the immediacy of the content) but we don’t have much of a lexicon for how it is working. If we might return to Ezra Pound’s triad of terms and their incapacity to describe the machinations of our #instapoetry, perhaps we might need to add a fourth term. I like to think that Ezra wouldn’t have minded a little experimentation.

My first offering to the spontaneous brainstorm between myself and my wordsmith mother was solapoeia (a nod to a psychoterratic neologism coined by my environmental philosopher dad Glenn Albrecht), which references the solace (noun 1. comfort or consolation in a time of great distress or sadness) given by the emotionally open and raw nature of the works. We then threw out the mouthful empathopoeia, which self-evidently comments on the empathetic shared experience in writing, reading and redistributing the poems. Another option, egopoeia, centres the narcissistic 21st century self as the focus of the works and recognises the desire of the reader to have the poem help them directly in some way, rather than addressing the wider world. The last, which we were happy to settle on – at least for a while – is the term therapoeia, which places the healing aspect of these works at the forefront.

After all, that’s what it seems to come down to – readers in this decade don’t want poetry that brings them down. They want to be uplifted, healed and restored by just a few well chosen (free) words. In a turbulent political and social climate, readymade self-love and acceptance is being offered. If that’s where poetry is headed, there’s no hope for some of us cynics. But we can all agree that this surge in the readership of poetry – artless or no – means big things for the form, and promises a generation of new poets and readers who might one day want to swim further out into the deeper dark ocean of poetry.

Header image: dismalpoetrywriter / H. Marshall – Instagram