Notes from Anzac Day, 2018

1.

On Anzac Day I’m driving north in the pre-dawn dark, through the coastal villages of southern New South Wales. At ubiquitous cenotaphs, pedestrians are gathering for Australia’s annual meditation upon the legacy of war.

I stop on the main street of a narrow riverside town, where perhaps 150 people have encircled a temporary dais before its local war memorial. Medals gleam from the breasts of neat suit jackets in the first pinks and greys of sunrise. In a small, colloquial community, not ordinarily given to formality, the faithful reiteration of this ceremony is an objective oddity.

But there are no surprises at a Dawn Service. The primary function of ritual is continuity. A local politician recites a venerable checklist of Australian attributes – courage, sacrifice, mateship, endurance – indelibly fusing our contemporary congregation to those who on this same day in 1915, he says, ‘stormed ashore at Gallipoli for the love of country’.

2.

The conceptual scaffolding of Anzac Day begins to collapse the moment its central orthodoxies are reframed as questions:

Did the Anzacs die defending Australia? No. They were deployed by Britain, against a sovereign state, in a war born of intractable Eurocentric tribalism. The distant Ottoman Empire presented no threat to Australia. If symbolic of anything, Gallipoli was a reaffirmation of Australia’s deference. A deference which, from Vietnam to Iraq, finds continuity under the contemporary imperialism of the United States.

Were the Anzacs nonetheless honourable, selfless and heroic? It is conceivable that some young men left Australia with those inclinations. Perhaps a few maintained them throughout the enactment of war, or attempted to. But as a collective, the Anzacs were far from admirable. Even in the estimation of their British contemporaries, the Anzacs quickly gained a reputation for unchecked barbarism, for the summary execution of prisoners, and for the ‘sport’ of racialised bloodshed. In Egypt, for example, while awaiting deployment to Gallipoli, the Anzacs rioted, set fire to brothels, and ‘thrashed impudent niggers with whips’. In 1918, the Anzacs massacred the inhabitants of a Bedouin village in Palestine, before burning it – and the village of nearby nomads – to the ground. In Australia, however, evidence-based history can equate to cultural heresy, and recusant media commentators have occasionally been forced into physical exile.

Did the Anzacs, then, articulate something essential to Australia’s national character? Well, yes, perhaps they did. In the savagery of slaughter – and the Anzacs’ pretension to both racial superiority and divine mandate – the event of Gallipoli can be seen as congruous with Australia’s colonial trauma. The capacity for violence, for which the imperial resource of Australian soldiery was distinguished and exploited, was no historical aberration.

During Anzac Day, dissenting academics, journalists and historians will again remind us that, in 1788, the Australian continent itself was attacked by marauding invaders who, through a long and deliberate program of dispossession, sought to exterminate its robust, existent nations.

Memorials to European wars dominate the civic space and lexicon of even the smallest Australian town, but for the Frontier Wars there is yet no national monument, no commemorative day, no museum and no outpouring of government funds. White invaders inflicted brutal massacres, poisonings, kidnappings, rapes, slavery, infanticide and the destruction of language. From this base, they codified and institutionalised a racial apartheid, not officially dismantled until the mid-1970s and still throbbing within the DNA of contemporary Australia.

From the first spear thrown at James Cook’s arrival, Aboriginal nations fought this onslaught. In the defence of their country, the fact of Aboriginal resistance exponentially eclipses the Anzacs’ European campaigns on terms of both virtue and national relevance.

3.

But this is not a day for analysis. Through its morbid religiosity and nationalist fervour, the Anzac narrative insulates itself against the intrusion of historical accuracy. If the foundations of Anzac Day are demonstrably baseless, we must then consider the cultural function – and identify the beneficiaries – of its enduring emotional architecture.

Anzac Day has proved an easy mantle for the patriot, for whom the First World War ‘digger’ is an ever-popular avatar. Australian patriotism frequently invokes the ‘spirit of the Anzacs’ against both the minorities within its borders and the refugees without. Racism is by nature inarticulate, but grafting the overwrought vernacular of Anzac Day to an indefensible position furnishes the patriot with a blunt rhetorical readymade: the weight of folklore, the gravity of blood sacrifice and, perhaps most significantly, the abiding male fantasy of righteous violence.

This is no accident. Australia’s two ‘national’ days are tandem figments, inflicting their respective pageantries – in diametric symmetry – upon the collective memory. While 26 January falsely demilitarises Australian history, Anzac Day falsely militarises it. While the former reframes invasion and massacre as mere ‘discovery’ and ‘settlement’, the latter inflates and fetishises Australia’s ignominious role in a foreign military horror to inculcate a new epicentre of Australian identity.

Over time, a national inventory of the cultural ephemera that Anzacs supposedly ‘fought and died for’ is liberally expanded. At this particular Dawn Service, in this particular coastal village, I am told that that the Anzacs gave their lives willingly for democracy, for freedom, for equality, for a ‘fair go’; and have hence ensured the safety and affluence of all assembled. In truth, the Anzacs died for none of these things, their deaths were definitively senseless.

4.

Today, however, my destination is the Ceremonial heart of Anzac Day: the grand, fascistic promenade of Canberra’s Anzac Parade. Specifically, I want to observe a small event on the fringe of the National Ceremony. Now in its seventh year, the Frontier Wars March is led by Ghillar (Michael Anderson), Convener of the Aboriginal liberation movement Sovereign Union, last surviving member of the Aboriginal Embassy’s founding four and leader of the Euahlayi Nation. In his letter of intent (6), distinguished by its civility and restraint, Ghillar alerts the Australian War Memorial and Retired Servicemen’s League to:

colonial battles, the massacres, poisoning of waterholes and flour and other forms of killing that pervaded the whole colonial expansion throughout this Continent, popularly referred to as ‘clearing the land’ not just of trees and forest to create open land pastures, but to clear away the original owners and occupiers.

Ghillar explains that, as in previous years, his is ‘not a demonstration, nor protest’, but a ‘solemn March of Remembrance of those innocent people who dared to defend their sacred right to their Country’. He asks that his group be permitted to lay a single wreath at the National cenotaph, in memory of those who died in the Frontier Wars. He also requests that the Frontier Wars March, like other delegations, be announced before the conclusion of the official Ceremony.

The written response from Australian War Memorial Director Brendan Nelson is curt and evasive. He writes of the AWM’s recent efforts to recognise the fact of Aboriginal participation in the Australian military, but avoids discussion of the Frontier Wars, concluding that:

All attendees to the ceremony are welcome to place wreaths at the conclusion of the National Ceremony. As in previous years your group would be welcome to do so, however I can advise that this will not be formally announced.

What Nelson means, in practice, is that the Frontier Wars March will be held back from the Ceremony by a police line until the cameras are off and the show is over. Only then will it be permitted to find a path to the cenotaph, through an unceremonious confusion of empty plastic chairs and departing dignitaries. The Frontier Wars wreath will eventually be laid, and the occasional veteran will pause, mid-exit, to acknowledge the ceremonial smoke of the Aboriginal delegation with quiet applause. In spite of Nelson, this will be a modest act of symbolic significance.

While the AWM nominally commemorates ‘all who have served’, it does not acknowledge the Frontier Wars, explaining that:

The story of Indigenous opposition to European settlement and expansion is one that should be told, but which cannot be told by the Memorial. As defined in the Australian War Memorial Act 1980, the Memorial’s official role is to develop a memorial for Australians who have died on, or as a result of, active service, or as a result of any war or warlike operation in which Australians have been on active service.

In using the terms ‘settlement’ and ‘expansion’, the AWM butters the tired colonial euphemism for invasion with the notion of progress. The colonisation of Australia, it implies, was not sufficiently ‘warlike’. The AWM then excuses itself from any further engagement with the issue, explaining that:

Today, the Memorial’s Council continues to adhere to [WW1 correspondent Charles] Bean’s concept of honouring the services of the men and women of Australia’s military forces deployed on operations overseas on behalf of the nation.

Despite the Memorial’s continued expansion, and its apparently limitless public funding, its ideological charter is apparently hamstrung. Nelson is pleading technicality, but this is mere obfuscation from a Director who recently proposed that the AWM formally commemorate Navy personnel for their role in turning back the boats of asylum seekers. UNHRC condemnation aside, this inclusion would satisfy none of his, nor Bean’s, conveniently malleable criterion.

In truth, to sincerely acknowlede the Frontier Wars would disrupt the very premise of Anzac mythology: its contrivance, and annual reaffirmation, of a white-Australian origin story.

A quote from Bean is printed, incidentally, on Nelson’s correspondence to Ghillar. While this is no doubt a standard AWM letterhead, Nelson would have struggled to contrive a more insulting irony:

Here is their spirit, in the heart of the land they loved, and here we guard the record, which they themselves made.

5.

I reach Anzac Parade in the early chill of dawn and share a makeshift campfire with Bob, a Wiradjuri man, who provides a circuitous history of the Frontier Wars March, interwoven with his personal narrative. Contrasting the stiff and voluminous lines of uniformed military, the Frontier Wars March takes the shape of a small, respectful rabble; of fluttering banners and spirited children. The group’s dissenting placards do not contest Anzac Day; instead they simply date massacres in small, emphatic lettering. As I take my place in the procession, the nearest sign reads:

1825

Windamere Flat Massacre

200 Wiradjuri women and children forced

to jump to their deaths off a high cliff

Countless atrocities are likewise listed on two rolls of yellow fabric, unfurling to flank the March. Walking behind the official procession, we progress slowly towards the National Ceremony, pausing regularly for those ahead in the queue, whose wreath-laying has been deemed of greater merit; whose historical losses are apparently more deserving of commemoration.

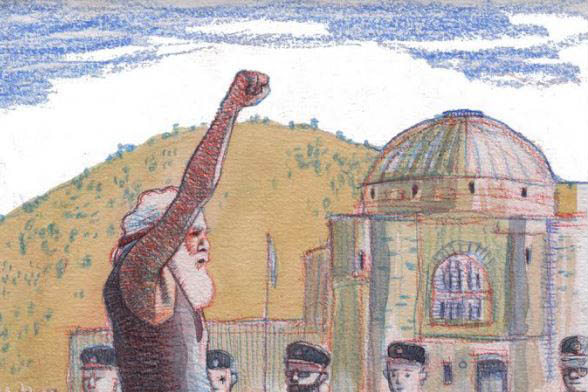

As we finally reach the War Memorial, police step forward to forcibly sever the Frontier Wars March from the official procession, but there is no attempt at resistance to what has apparently settled into an annual stalemate. From here, the Aboriginal delegation quietly observes the hymns, anthems and funereal intonations of a Ceremony from which it has been routinely excluded.

As former politician and diplomat Kim Beazley begins his Ceremonial Address, I break away from the March and mingle with a small media contingent being tolerated beyond the barrier. From this vantage point, I watch the faces of elders as they stand, restrained by a police line, fists raised towards a now biting midday sun. Their capacity for grace and forbearance is humbling. For those fighting to ensure the survival of over 60,000 years of complex and continuous habitation, an extraordinary outrage must rightly be tempted by Beazley’s opening words:

‘As we gather today our thoughts are not here. In our imagination we are looking back to 100 years. We are with our honoured ancestors.’

1917, Beazley states, was Australia’s ‘bloodiest year’. Yet, even in this embellishment, his is not an oratory of contrition or horror. Rather, in its evocation of the Anzacs’ bombs and bayonets, the foreign accolades, their military prowess and ‘impact on world history’, Beazley’s is the vicarious swashbuckling of a Boys Own Adventure, albeit delivered in the monotone affectation of a sacred rite. But this is standard Anzac liturgy; we’ve heard it all before.

Australia has spent over 500 million dollars, in the last four years alone, on the promotion of Anzac Day, and a further 500 million has been flagged for an expansion to the AWM. It is difficult to imagine that a deeply conservative government would feel compelled to ornament – at such great expense – the observance of self-evident truths. But to ensure wide participation in the collective performance of a demonstrable falsehood it must provide the opiate of ritual, the distraction of public spectacle and the bewilderment of an ever-expanding infrastructure.

‘The day was not a product of officialdom,’ concludes Beazley. ‘Anzac Day is a popular creation.’ As if to immediately underscore the conspicuous propagandism of this statement, an airshow of deafening Hornet warplanes thunders overhead, to the rapturous cheers and applause of attendees. Furious engines shake the big sky above Ngunnawal country and the soul of Anzac Day is, in that moment, perfectly exposed.

Image: Matt Chun