Amid the sequins, rainbows and glamour that took over Sydney on Saturday – Mardi Gras night – I was there, marching in a small group of queers wearing navy blue coveralls, made more fabulous by high-waisted belts; our chests gleamed with gold insignia, befitting our newly formed group, the Department of Homo Affairs. We’d joined the parade with the intention of getting in the way and turning back a morally leaky float.

As queers with a stake in the Mardi Gras party – and its proud history of protest – we consider the Liberal and Labor Party floats unauthorised arrivals; they’re dangerous vote-seekers jumping the queue, and they’re terrorising the values that we hold dear. So we handed out flyers with a grave warning: ‘The risk is real and growing. Illegal floats are stealing your blow jobs.’

The major political parties arrived at Mardi Gras intending to get full mileage out of recently legislated marriage equality, claiming it as their ‘victory for gay rights’. But we were there to remind them that human rights aren’t there to pick and choose when electorally expedient, and disregarded when inconvenient.

The Department of Homo Affairs intercepted the Liberal Party float as it entered Oxford Street, marching ahead with a banner that read, ‘Turn back the float. Justice for refugees.’ We stopped them in their tracks at various points along the parade, with the aim of turning back the unwelcome float.

Late last year Australia celebrated same-sex marriage as a win for civil rights and equality – and at exactly the same moment, our government cut off food, water, medical supplies and power to refugees on Manus Island. The community demanded that the government close the camps, and when at last those detention centres were found to be illegal, our calls were answered in the most brutal way: we watched as refugees were left to starve in abysmal conditions, and as their peaceful protests were met with violence.

This abuse of power is ongoing – and we simply couldn’t bring ourselves to march alongside the political parties that orchestrated such suffering. Having been forcibly ejected from the Manus Island detention centre, refugees are now languishing in hastily built ‘transit centres’ in Lorengau. There are fewer fences, but they are not free.

It is time to stop the floats that smuggle in politicians who pose a direct threat to freedom of movement and the right to seek asylum. It is time to lay claim to our stake in Mardi Gras – an event born as an act of resistance – and turn the logic of exclusion back on itself. Instead of marching with the Labor and Liberal floats – an acknowledgement that we tolerate their actions – we revoked their social licence.

Forty years ago, Sydney’s first Mardi Gras began as a celebration and a political demonstration that commemorated nine years since the Stonewall riots in New York, and demanded homosexual sex be decriminalised in NSW. With chants including ‘stop police attacks on gays, women and Blacks’, it was a demonstration that connected different forms of oppression. In 1978, Mardi Gras grew out of, and enacted, international gay solidarity, and it is in this tradition that we continue.

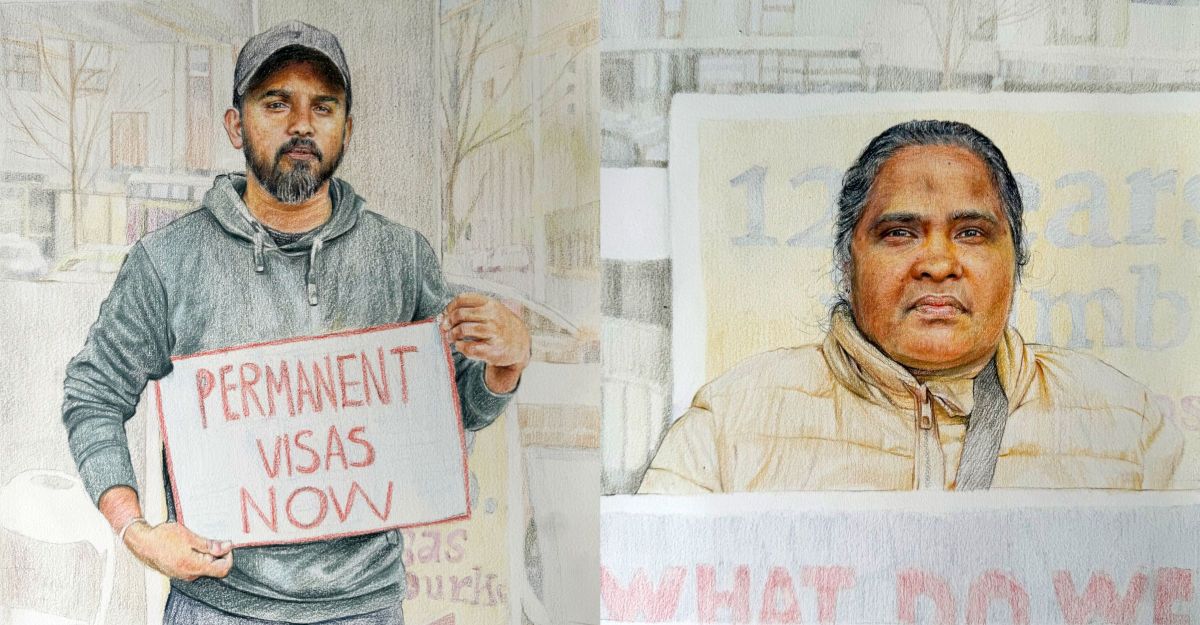

Despite the current trend that’s seen Mardi Gras overtaken by corporates, with every big business from ANZ to Netflix paying for floats at the front of the parade, Mardi Gras CEO Terese Casu has called the event ‘a loud and proud platform for social justice’. Which is why this past weekend was the perfect opportunity to convey a message of international queer solidarity, and to express support for refugees on Manus Island who, in a plea for freedom, have been holding a continual, peaceful protest for more than 200 days.

The situation on Manus Island is particularly shocking, but the cruelty inflicted by Australia’s border policies extends much further than that – to onshore detention, to refugees stranded in Indonesia with no hope of resettlement, and to 65 million displaced people around the world who now have fewer options for resettlement than ever. At Mardi Gras time, it’s especially worth remembering those refugees who are seeking asylum on the basis of their sexuality, and whom Australia refuses to protect.

Over the last decade, a succession of name changes has seen the Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs become rebranded as the Department of Home Affairs. This shift points to the growing militarism and obsession with policing borders at the heart of Australia’s immigration policies. It is important to remember that within these borders, our homes sit on stolen land; and the vigilance with which our borders are guarded is consistent with the violent way this country was seized from Indigenous peoples.

Refugees and asylum seekers are often, and falsely, marked as threats to national security and linked to terrorism. Refugees and asylum seekers are referred to as ‘illegal arrivals’, wrongly suggesting that they are criminals. The first generation of Mardi Gras marchers remember when queers were criminals, harassed and entrapped by police. They still remember the 53 arrests, and the night of bashings at police hands. It’s part of the same thread of state violence that punishes refugees for seeking asylum, and for their powerful resistance even within a detention regime that threatens their very survival.

Our float was always unlikely to be met with that state violence, even though we engaged in an act of civil disobedience. Even as queers, we’re protected by our relative privilege. But that is precisely why we protested – we were responding to a call from RISE (Refugees, Survivors and Ex-Detainees) for supporters to use their social capital to apply consistent pressure on the political parties complicit in the inhumane treatment of asylum seekers and refugees.

On this fortieth Mardi Gras, it is important to celebrate how far we’ve come since that night of arrests, police bashings and the fight for decriminalisation. But the sparkles and bright lights shouldn’t blind us to the hypocrisy of those who want to join the party even as they continue to practice the politics of exclusion, and actively inflict a brutal regime of violence against those on the margins.