What follows is, as far as I know, the first translation into English of the lengthy written interview that Amadeo Bordiga gave to journalist Edek Osser in 1970, shortly before his death.

An important figure in Italian and European communism, Bordiga was every bit as prominent as his friend and rival Antonio Gramsci in the decade following the Russian Revolution of 1917. As leader of the abstentionist faction of the Socialist Party, he was at the centre of the split that led to the founding of the Communist Party of Italy, of which he served as secretary while Mussolini seized power. In the interview, he is repeatedly asked to account for his steadfast refusal to seek alliances and form a united front against the Fascist threat. Unrepentant, he explains that he viewed the prospect of an alliance between communists, reformists and liberals as the worst possible consequence of Fascism, and the ultimate betrayal of revolutionary Marxism. As such, he remained staunchly opposed to the principles on which the Italian Republic was eventually founded, after the fall of Mussolini and the end of the war.

This intransigence led in 1930 to Bordiga’s expulsion from the Communist Party at the hand of Gramsci and Togliatti. He was to spend the last four decades of his life at the margins of the movement, of which he remained a critic in his writings. Finally, at the age of 81, he gave his first and last interview. Some have called it a testament, but it leaves no instructions for the future. It is, rather, a witness account – written with searing, almost obsessive precision – of some of the most crucial political events of the twentieth century.

Bordiga never changed his mind. He thought that a revolution in Europe was possible, that it had been possible. For the historical consequences of this intransigence, he should fairly be judged – the question, ‘could Fascism in Europe have been averted?’ is both legitimate and important. But any such judgment should not detract from the accuracy of some of his analyses, particularly on the social nature and origins of Mussolini’s movement. Above all, however, what follows is a lucid historical examination of the revolutionary method. And for that reason, it still demands to be read.

- In November of 1917, you took part, in Florence, in a secret conference of the ‘intransigent revolutionary’ current of the Socialist Party. On that occasion, you exhorted socialists to take advantage of the military crisis and take up arms to deal a decisive blow to the bourgeoisie. What was the outcome of your proposal? Had the revolutionary situation reached its maturity in Italy in your opinion?

Yes, I took part in November 1917 in Florence in the secret conference of the ‘intransigent revolutionary’ faction of the Socialist Party. This had been the guiding, majority component of the Italian Socialist Party since 1914. The leadership was informed that the conference had been convened, and didn’t denounce it. It was in fact represented.

It’s on this occasion that I first met Antonio Gramsci, who showed great interest in my speech. My impression to this day is that his uncommon intelligence led him, on the one hand, to share and completely agree with my radical Marxist propositions, which he appeared to be hearing for the first time; and, on the other, to articulate a subtle, precise and polemical critique, which already emerged from the substantive differences between the positions of our respective periodicals: Il Soviet, based in Naples, of which I was the editor, and Gramsci’s L’Ordine Nuovo, which was based in Turin. These contrasting views had been clear to me since I welcomed the announcement of the founding of Gramsci’s magazine. In that short article, I noted that its avowed pragmatism revealed a gradualist tendency that would no doubt lead to concessions to a new kind of reformism, and even right-wing opportunism.

My reading of the forces in play at that time was concerned not with Italy alone, but with the whole of the European situation. Obviously, I developed in full my condemnation of the socialist parties of France, Germany and so forth. These had openly betrayed the Marxist teachings on the class struggle, opting instead for the malicious politics of national harmony, sacred unity and support for the war waged by the respective bourgeois governments. My speech exposed, in doctrinarian fashion, the false ideological justification for supporting the war waged by the Entente against the Central Powers, to which our sworn enemy – Italian military interventionism – had subscribed. The basis of my position was to repudiate the fallacious preference – common to war-mongers of all nations – for the parliamentary democracies of the bourgeois regimes, against the so-called feudal, autocratic and reactionary ones of Berlin and Vienna, while saying nothing about the regime in Moscow. As I had been doing within the movement for decades, I followed the critique inaugurated by Marx and Engels, attempting to show how stupid it was to expect that a future democratic Europe would arise from the military triumph of the Entente.

The position I took at this time coincides with what Lenin called ‘defeatism and repudiation of the defence of the mother country’. I put forward the claim that the proletarian revolution could have triumphed, had the armies of the bourgeois states been defeated by their foreign enemies – a prediction which history confirmed in Russia in 1917. It is true, then, that in Florence I proposed we should take advantage of the military disasters incurred by our monarchist and bourgeois state to give impetus to the class revolution.

This proposal did not coincide with the political line of the party leadership which was stuck on the disgraceful formula coined by Lazzari to ‘neither support nor sabotage’. However, those who took part in the conference (already a de facto left-wing of the Socialist Party) appeared to wholly support it. For us, the fact that the Italian party had not adhered to the government’s war policy, refusing to give it a vote of confidence or support the relevant military funding, was not enough. This line could not extend to the opposition to sabotage, which Lenin later called ‘the transformation of the war between the states in a civil war between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie’. My position, therefore, was not exactly that in Italy there existed the conditions to wage an armed war against the power of the propertied classes. But rather another, much broader one, which was later vindicated by the course of history: namely, that while the war raged in Europe we could have and should have escalated the revolutionary conflict on the most opportune fronts (which Lenin later called ‘the weakest link of the chain’). The conflict would certainly spread to all the other countries. The aforementioned, false merit of the Italian party in choosing both to refuse to support the war and to reject revolutionary sabotage, was later spuriously invoked by Serrati and his followers in opposing the expulsion of the reformist right (which was in fact both social-democratic and social-chauvinist) on the occasion of the founding of a new International that might redeem the disgraceful failure of the Second (an outcome I had foreseen on behalf of left socialists at the Congress of Rome in February of 1916). This is demonstrated by the fact that the Italian Socialist Party had refused to go down the sole strategic path that – ever since Lenin, having returned to Russia, articulated his classical theses in April of 1917 – fulfilled the doctrinarian predictions and historical aims of revolutionary Marxism. From a historical viewpoint, it seems certain that – had the delegates at the Florence conference decided to go to a vote – they would have undoubtedly supported the bold thesis of torpedoing in any way possible the war policy of the capitalist state. Seeing as the conclusions of a consultation such as ours ought to have involved the central organs of the party, my proposal should have resulted – in a healthy movement – in the appropriate implementation measures. But we couldn’t hope for the leadership to take such action, having been already compromised by their refusal to call for a general strike in May 1915 against the preparations for war, as we had requested; as well as by the already mentioned slogan ‘to neither support nor sabotage’; and by having tolerated, at a pivotal juncture of the war, that the Socialist parliamentary contingent followed their leader, Turati, in shouting the chauvinist slogan: ‘Our homeland is on Monte Grappa’, which was not far removed from the behaviour of the French and German social-traitors.

- In 1919, Italy was shaken by violent demonstrations. Why did this not result, in spite of the socialist propaganda and the numerical strength of the party, in a popular revolutionary movement? Were the masses not willing and ready to fight? What prevented the launching of a revolutionary offensive?

After the war ended with the victory at Vittorio Veneto, which brought much glory but few lasting effects, the whole country versed in the state of malaise and economic crisis that – as even the most moderate socialists are wont to claim – afflicts the working classes at times of peace between the bourgeois nations, but is made even worse by the effects of war: beginning with the violent upheaval of workers from the quiet environment of their poorly rewarded productive activity, which plunges them and their families into an even greater poverty. This inevitable state of widespread malcontent did not cause the proletarian masses to recover the collective historical consciousness that, unfortunately, the Party itself had largely lost. The natural consequence was a new wave of protests and claims for immediate improvements of working conditions, including salaries. These made the ground shake under the feet of the bourgeois, but did not by themselves create in the proletariat the capacity to plan objectively for armed struggle and the advent of their dictatorship.

Today, what we can say is not that in 1919 there existed the conditions for a socialist revolution in Italy, but rather that – after the end of the First World War – the parties of the proletariat could have assumed the leadership of a successful offensive movement. If this didn’t happen, it’s only because those parties betrayed their own ideological heritage and the vision of their own historical struggles, which could have brought the capitalist era to a close. That was the true and fateful moment in which to rebuild the proletarian and socialist movement, restoring the true doctrinarian foundations of its programme and strategy. It was to this task that Lenin and the Communist International applied themselves without hesitation, and to which the left of the Italian movement subscribed, thereby demonstrating – as it remains true to this day – their full allegiance to the glorious, historical line of the worldwide anti-capitalist revolution, which began in 1848 with the manifesto penned by Marx and Engels.

- At the sixteenth Congress of the Socialist Party, in Bologna in October 1919, you spoke on behalf of the so called ‘abstentionist’ faction, which argued for the necessity to withdraw from elections in order to concentrate con the revolutionary project. Why were the two activities incompatible, in your view? What was the advantage of the line you advocated?

At the sixteenth socialist congress, held in Bologna in early October 1919, the abstentionist communist faction (whose organ was Il Soviet, the newspapers founded in Naples in December of 1918, immediately after the end of the war in Europe) did not stand out from the other currents only for advocating withdrawing from the upcoming general election and the resulting parliament, but also for being the only one to espouse the ‘theses’ of the founding congress of the Third Communist International, held in Moscow in March of that year, which translated the magnificent historical experience of the Russian Revolution of October 1917. Foremost among those theses was the conquest of political power not through the bourgeois democratic structures, but through the advent of the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat and of its Marxist class party. The prospect of a great election campaign and the foreseeable triumph of the only party that had truly opposed the bloody and disastrous war of 1915 was rejected in my speech as a diversion from the tension that was growing among the Italian masses due to their immense blood sacrifice on the battlefield and the dire economic crisis at the aftermath of the war. Thus, it openly contradicted any hope and opportunity to channel that tension, that unease, that widespread malcontent, in the only direction that – as history was showing us – could lead not just Italy but all of Europe to a socialist and revolutionary outcome. These theses were fundamental to the thinking of the abstentionist faction, which was organised from the outset and uniformly spread in all parts of Italy. However, they could not be presented and supported in front of the other currents at the congress, which were satisfied with the prospect of a large electoral victory that might enable the party – through parliamentary manoeuvres – to pass measures capable of alleviating in part the crisis and meeting the anxious expectations of the working masses. Such an outcome would have definitively squandered the favourable aspects of the situation and blocked the only path through which, from then on, the entire movement of the exploited classes would have had to exert its pressure: in other words, it would have prevented the working class and the Party itself from recovering their true revolutionary conscience. The reformist right of the Party openly condemned the vital communist theses; and the large current that called itself ‘maximalist’, whilst not rejecting those principles, didn’t see why this historical programme should be dictated not only to the Party as a whole, but also to its individual supporters and militants, whom – in case of stubborn opposition – should have been expelled from the party. This was the only way to rebuild a new International movement safe from the risk of repeating the horrendous catastrophe of August 1914, and that could be cured once and for all from the infectious disease of social-democratic and minimalist opportunism.

Ever since the Bologna congress, then, the abstentionist faction had set itself the task of breaking the unity of the Socialist Party. Because of its large membership and foreseeable electoral victory, that unity led the pro-election faction into a grave mistake: thinking that it would be possible to march towards proletarian socialism whilst repudiating the use of violence and armed conflict, or the recourse to the fearsome historical measure of the dictatorship – the key objective of which would be to deprive of every electoral and democratic right (as well as of the freedom to organise and propagandise) the sectors of the population not formed by actual workers.

Here I think that it’s appropriate to remember an episode that, all these years later, seems of real historical significance. The central aim of our faction wasn’t to oppose elections, but rather to split the Party, in order to separate real communist revolutionaries from the ‘revisionists’ of Marx’s principles concerning the inevitable, catastrophic outbreak of the conflict between opposing classes, as predicted most recently before the war by the German Eduard Bernstein. To test our thesis, we proposed to the leaders of the pro-election, maximalist group – which included Serrati, Lazzari and Gramsci – to replace the document they had prepared with a single, much more sharply anti-revisionist one. In this text, we would have agreed not to call for boycotting the election campaign, in exchange for their support of our basic thesis that the Party should split. Our proposal was sharply rejected by the maximalists. I shall note that, shortly thereafter, Lenin – drafting his text on extremism as the infantile disorder of communism – wrote that he had received and read a few issues of Il Soviet and that he considered our movement the only one in Italy to have understood the necessity to separate communists from social-democrats, by splitting the Socialist Party.

- In 1920, at the Second Congress of the International in Moscow, your ‘abstentionist’ thesis clashed with Lenin’s ‘electionist’ position. Lenin prevailed and the International ordered that the Italian Socialist Party contest the election. Do you still believe that the decision of the International was a mistake? Even though the 1921 election was a great success for the Socialist Party?

The Second Congress of the Communist international began in Leningrad in June 1920 and continued in the former Throne Room of the Kremlin. The Italian Socialist Party – which already claimed, since the Bologna Congress, to be a full member of Communist International – sent a delegation which was granted deliberative votes and consisted of Serrati, Bombacci, Graziadei and Polano (for the youth federation). The group reached Russia in a special train, as part of a broader Italian proletarian delegation which included: D’Aragona and Colombino, for the trade unions; Pavirani, for the League of Co-Operatives, and others who naturally were not invited to take part in the World Congress. As for me, as a member of the Italian abstentionist faction I was not part of the Party delegation. My speech was included and organised by Lenin himself through his Italian representative, Mr Heller (although we called him Mr Chiarini). Heller came to Italy several times to organise my trip, which was beset with difficulties that I’m not going to get into. The route I travelled was Brenner-Berlin-Copenhagen-Stockholm-Helsingfors-Reval and, finally, Leningrad. I was there from the first session, during which Lenin gave a memorable speech followed by a standing ovation that lasted over an hour. Given my peculiar position, I took part in the works of the Moscow Congress in a consultative role only. It was immediately decided that I should be admitted as a co-rapporteur on the question of parliamentarism, which was included in the agenda with Bukharin as the lead rapporteur. The decision was taken by the Executive and by its president, Zinoviev. In the early stages, another important debate took place concerning the admission criteria of the parties that asked to be included in the Communist International. A committee of which I was part was appointed to examine the proposals, which resulted in the famous ‘21 points of Moscow’. Thus, I was able to raise again a proposal of Lenin’s, whose rigorous twenty-first point required individual parties to review their programmes. This was vital for the Italian Socialist Party, which remained partly tied to the social-democratic programme drafted in Genoa in 1892. I also covered this topic during the plenary assembly, advancing the most drastic and radical solutions against the wishes of the other Italians and of the right. The debate on the issue of parliamentarism was opened by Bukharin, who explained the beginnings of his thesis, while I spoke in opposition to taking part in elections. Bukharin’s position was taken up in a statement by Trotsky, and later by other speakers including Lenin, who openly criticised my theses and their underlying argument. In a recent piece for the Marseilles magazine Programme Communiste, I tried to reproduce faithfully the words and thoughts of Lenin on this topic. With his usual verve, he said: ‘If it’s a fundamental task of the revolutionary party to foresee the plans and the actions of the enemy state powers, how can we pass up on such a valuable vantage point as the parliament, in which states have historically developed their future policies?’

The Congress voted by a large majority in favour of taking part in parliamentary elections, suggesting that all socialist and communist parties should follow suit, and not just the Italian party as the question implied. The Italian general election of 1921 saw the participation not only of the Socialist Party – who couldn’t have asked for more – but also of the Communist Party of Italy, founded shortly after the Second Congress in Moscow.

The election success did not advance the revolutionary movement in Italy at all, contrary to what the Bukharin-Lenin thesis had suggested. I opposed them then and I would do so now, after a long historical experience: especially with regard to Germany, whose failed insurrections in the Spring of 1921 and Autumn of 1923 belied the strategy chosen in Moscow. Returning for a moment to the vote of the Second Congress, it may be worth pointing out that I dissuaded from actually supporting my thesis several delegates who opposed parliamentarism not on Marxist grounds, but rather due to weakness or sympathy for the revolutionary syndicalist and libertarian methods popular among some groups in Germany, the Netherlands, England and the United States. In the vote for the admission criteria it had already been stated that in Italy – like in every other country – our parties should have been purged not only of the non-revolutionary reformists on the right, but also of the currents that Lenin called ‘centrist’, and that could be identified in Germany with the followers of Kautsky, and in Italy with the maximalists and the followers of Serrati.

- You were the first to advocate, since 1917, the expulsion from the Socialist Party of the right-wing current, the so-called reformists. In 1920 this debate reached the Congress of the Third International, which voted for the expulsion. Why was this decision not enacted? What role did this outcome play in the foundation of the Communist Party?

If we were unable to exclude the reformists as Moscow requested, it was due to the resistance and obstruction of the maximalists, who leveraged their numerical superiority over our faction first in the Socialist Party, then in the Socialist Congress, which decided not to fully apply Moscow’s directives. This had a positive consequence, since during the creation of the new Communist Party it became possible to exclude both the reformist and the centrist-maximalist elements.

- At the same Congress of Moscow, in 1920, your conduct led some to believe, as reported, that you ‘without daring to say so, were afraid of the influence of the Soviet state on the Communist Parties, and the temptations of compromise, demagogy and corruption; and that, above all, you did not believe that a peasant Russia was capable of guiding the international working-class movement’. Does this interpretation correctly reflect your thinking?

I did in fact harbour the reservations stated in your question, and articulated in the quotation from Victor Serge. I still think that there were serious drawbacks in the direction dictated by Moscow, which had little revolutionary value in the Stalin era, after the death of Lenin in January 1924. As evidenced by the further disputes of the following years, the strategy dictated by Moscow was not always inspired by the real revolutionary dynamics that would have benefited the worldwide communist proletariat, but was influenced rather by the sometime clashing interests of a vast state machinery founded on a small peasant base, therefore ‘petit-bourgeois’ according to the definition that Lenin himself gave. If it’s true that these concerns can be deduced from my conduct during the 1920 Congress (see, for example, my last speech after the words of Lenin), it proves only that our Left Communist current was the first to predict and denounce the dangers of a degeneration of the Third International from its glorious beginnings.

- In 1920, the occupation of the factories represented the culmination of the unrest that was taking place throughout the country. This episode reflected the hopes and the efforts of the communist group based around L’Ordine Nuovo in Turin and the figure of Antonio Gramsci. Were you also persuaded that this was the road to revolution? In what ways did your positions diverged at this time?

The proletarian movement that led to the occupation of the factories reached its apex in the Autumn of 1920, after the Italian delegation at the Second Congress of the Communist International returned from Moscow. The analysis by the groups of L’Ordine Nuovo and Il Soviet regarding the possibilities of a revolutionary outlet were very different at this time, if not diametrically opposite. Criticising the Turin group, Il Soviet wrote: ‘Seize power or seize the factory?’. Developing all the arguments of principle, we rejected the notion that the communist revolution could begin by workers seizing the factories and taking over their economic and technical management, as Gramsci believed. According to our position, the workers’ forces should have attacked instead the prefectures and police headquarters, in order to foment a general insurrection capable of achieving, after the proclamation of a general strike, the political dictatorship of the proletariat. This vision was evidently well-understood by the capable and intelligent leader of the Italian bourgeois forces, Giovanni Giolitti. Giolitti refused to acquiesce to the industrialists’ demand that law enforcement intervene to expel the occupying workers and give the workshops back to their owners. He believed that leaving the factories in the hands of the workers meant giving them a blunt weapon which couldn’t threaten or overturn the power and privilege of the capitalist minority. The workers’ control of the means of production would certainly fail to lead to a non-private regime of social production. Our tactical position consisted in urging the proletarian class party to pursue control not of the factory councils and of the councils of the workshop commissars – as advocated by the Ordine Nuovo group – but rather, above all, of the traditional industrial organisations of the working class. In this regard, my views sharply differed from Gramsci’s, and I never conceded that the general occupation of factories would lead, or could ever lead, anywhere close to the social revolution that we aspired to.

- The communist faction of the Italian Socialist Party was founded in Imola in 1920. What were its aims? Had the decision to split from the Socialist Party already been taken?

The communist conference held in 1920 in Imola accepted without reservation the decisions of the Second World Congress, including admission to the International and, therefore, the expulsion of the reformists from the Party. The conference included members of both the Ordine Nuovo and Soviet groups, among others. The latter announced the public dissolution of the abstentionist faction, by ceasing to uphold the anti-election thesis and pledging not to raise it at the Congress of the Italian Socialist Party (although it did not rule out proposing it at future meetings of the Communist International, once the actual effectiveness of the Bukharin-Lenin line on revolutionary parliamentarism had been tested). It was decided, with the full assent of the delegates from Turin and Naples as well as Milan and other cities and regions, to found the communist faction of the Italian Socialist Party. The objective of this new organisation was certainly not to gain the majority of votes at the Congress in Livorno, but rather to lay the foundations of the real communist party, which could only result from the open split between the followers of Moscow and the others. For it was clear that the numerically superior maximalist current would never vote to expel Turati and his people. It was decided that the faction’s organ should be the fortnightly Il Comunista, to be published in Milan, and that the offices of the organisation would remain in Imola. This worked was tasked to me and Bruno Fortichiari. I clearly remember that, in a meeting with Giacinto Menotti Serrati before the Congress of Livorno, I did not attempt to disguise that we were creating the Communist Party of Italy, as opposed to seeking to become the majority faction of the socialist congress. The issue of the expulsion of the reformists had already been resolved and deliberated upon at the Congress in Moscow. All there remained to do was to carry it out from a disciplinary standpoint, burning the bridges with both the reformists and the maximalists – regardless of the outcome of the vote in Livorno. At the Congress of Imola, then, it had already been decided that – had we lost the vote – all of the communists already belonging to the faction would have abandoned both the Congress and the Socialist Party, and proceeded without hesitation to found the new Communist Party, section of the Third International.

- The Congress of Livorno sanctioned the split within socialism and the birth of the Communist Party. Why were you and the other communists belonging to the Imola faction so resolute in breaking off from the rest? What do you think of the objection that a split within the socialist forces had the effect of weakening further the popular front?

As should be clear from what I’ve said thus far, it was a profound belief of all the communists of the Imola faction that there would be everything to gain for our revolutionary aspirations in separating from the reformists and the maximalist centrists, and nothing to be regretted in losing the numerical strength we enjoyed before the Livorno Congress. The argument that, before the split, the proletarian front – which we always refused to consider a strategic weapon – would have had a broader base, had been demagogically advanced by all pro-unity types, including Serrati. Those who advocated the split, beginning with Lenin – whom we followed enthusiastically – always rejected it, persuaded that our course of action was the only one that could lead to revolutionary victory in Italy and Europe. Therefore, we had no hesitation whatsoever in preparing and carrying out the break-up, and I’m glad and also proud to have read out from the gallery of the Congress the irrevocable statement by all those who voted for the Imola motion. The group immediately left the hall of the Goldoni theatre and marched down to the San Marco theatre, where the Communist Party of Italy was founded. However, not everyone felt the same enthusiasm for that decision. One of the delegates, Roberto, gave a heartfelt farewell to the comrades we were about to leave and wished that we may be reunited soon, for the reasons cited in your question. It is likely that my disapproval of the sentimental feelings expressed by Roberto was not fully shared by Gramsci. In his memoir, eyewitness Giovanni Germanetto wrote that Gramsci paced nervously back and forth in the area of the stage behind the president’s table, muttering his concerns with his hands clasped behind his back. On the other hand, none among us – who responsibly placed ourselves in the broken off wing of the party – thought at that time that the action of the proletariat against capitalism and its reactionary forces could be demanded by the new party to an amorphous and ambiguous ‘popular front’ – that is to say an openly collaborationist bloc including proletarian currents alongside others that were more or loss confusedly petit-bourgeois. It is certain that Gramsci didn’t think so at this historical juncture either – not even in the face of Fascism, which had already made its appearance. For within that ‘bloc’ or ‘front’, there would have to exist an organ or committee bound to fatally tie the hands of the extreme party, that is to say its truly struggling and revolutionary component. Since that day and into the post-fascist period, I have always harboured constant horror for the total defeatism of that situation.

- The Communist Party ran its own, clandestine military organization since 1921. In the same period, you flatly refused to make use of [the anti-fascist militias known as] the ‘Arditi del popolo’, which had gained considerable strength throughout the country. Many regard that decision as a possibly fatal mistake. Vittorio Ambrosini, who in 1921 was in Germany, offered you to become the leader of the movement and launch the armed struggle. Why did you refuse? Did you regard the proposal as having political limitations, or were you concerned about Ambrosini himself?

The foundation congress of the Communist Party of Italy formed a Central Committee of fifteen members, including an executive formed by myself, the former abstentionist Ruggero Grieco, Umberto Terracini – who hailed from Turin but did not exactly belong to Gramsci’s Ordine Nuovo group – and Bruno Fortichiari and Luigi Repossi, from Milan. The executive set up its offices first in Milan – in the former customhouse at Porta Venezia – then in Rome at various locations, both open and covert. Repossi was put in charge of the trade union office, which was responsible for all the groups operated by the Party within the workers’ organizations, while Fortichiari ran the office of covert and military operations. This oversaw the armed squads established at all local and provincial federations of the party and of the youth movement. This network, whose central and regional addresses were kept secret strictly secret, was also charged with the encoded communications with both national and international communists centres, and with safeguarding the secrecy of the cable codes as well as of all the addresses – again both in Italy and abroad.

At the headquarters, Grieco and I took care of the general correspondence and of the instructions to the editors of the three party newspapers, which were: L’Ordine Nuovo in Turin, Il Lavoratore in Trieste and, as of a few months later, Il Comunista in Rome, a new incarnation of the fortnightly magazine of the Milanese faction mentioned above. There also existed, in various Italian cities, Party weeklies under the strict control of the Central Executive.

Before the famous initiative of captain Vittorio Ambrosini and the Arditi del Popolo, the central committee had to issue both internal and public directives in order to deal with another situation that threatened the Party’s internal organisational discipline: the first serious attacks against proletarian forces by the famous Fascist ‘squads’. The proletarian organisations and parties, who abhorred in principle the use of violence and pursued programmes of social peace, formulated a scandalous proposal for a ‘peace pact’ with the centres and the leaders of the Fascist movement, to be enacted both at a national and regional level. The Leadership of the Communist Party – alert to the perils of any kind of pacifism in the arena of social and civil confrontation, strictly fulfilled its duty by condemning this pact through public declarations and posters. Internally, we ordered that all communist organisations should firmly rebuff any such attempts at a local level. Today – not on my own behalf, but on behalf of the still-organised militants, young and old, who have remained faithful to the theoretical and tactical traditions of the Italian and international communist Left – I can state that our response to the issue of the Arditi del Popolo was perfectly consistent with the historical line we always followed. Not only there aren’t any mistakes for us to admit to, but – in the very same tradition – we always rejected any sort of participation in the National Liberation Committees, as well as Italian partisan insurrections and the various ‘popular fronts’ of infamous memory, which have more recently had detrimental effects also in France, Spain and other countries.

The Ambrosini proposal deserved no consideration whatsoever, not only because of its form but also of its substance and intrinsic content. The word arditi (‘daring ones’) had the same genesis of when it was applied to war veterans by nationalists and Fascists. Trying to connect this organisation to the much-abused myth of ‘the People’ means falling into the old anti-Marxist error that creates confusion instead of opposition between the social classes. Marx, Engels and Lenin always warned against this tendency of revisionist projects. As for the individuals involved, they are far less important than the serious underlying questions. At any rate, we were not aware in 1921 that Ambrosini was in Germany. According to our information, he had moved to Vienna, and we didn’t want to run the risk that our friends or even our main enemy should mistake him for an emissary or leader of the Italian communist movement. The Party Committee also had to prevent our base from confusing Ambrosini or its military operation with the organisation that we had already created. Another danger to be avoided was that that our peripheral groups might relinquish to Ambrosini and his men any of our arsenal, although the secret caches we had managed to assemble at that time were far from massive. Finally, the executive of a revolutionary party such as ours had another duty: to prevent a man like Ambrosini, either due to vanity or superficiality, from trading any powers granted to him to our adversaries, or promoting a new peace treaty with the Fascist forces that kept exerting their pressure upon the Italian masses.

- As the leader of the Communist Party, you have been accused of having underestimated, in 1921, the strength of Fascism, regarding it as a bourgeois phenomenon similar to others that preceded it, and to have failed to oppose it with sufficient energy when it would have still been possible to defeat it. Why did you oppose above all socialists, maximalists and reformists, who could have been useful allies against Fascism?

Our faction always rejected the thesis that Fascism could be opposed by a bloc of the three parties into which the old Italian Socialist Party had fractured – communists, reformists and maximalists. This is not a position we took in 1921 – as your question wrongly implies – and I refer you to the documents we tabled in Livorno, as well as before and after that Congress. We always regarded the other parties produced by the splits of Livorno and Milan as our most dangerous enemies, because their residual influence was openly opposed to preparing for the revolution. This thesis can be found in our conclusions at the Italian Communist Congresses of Rome (1922) and Lyon (1926), but had an even earlier origin. At the Socialist Congress of Bologna, in 1919, we invoked the opinion of Lenin, who – with a telegram to the leaders of the successful Hungarian revolution – criticised their grave mistake of inviting the socialists of that country into the dictatorial government. This, according to Lenin, was the cause of the eventual failure of that revolution. It ought to have been clear to everyone, then, that the Italian communists would reject any alliance with the socialists, both during the struggle to seize power and after (should that struggle have succeeded). As for my assessment of the historical phenomenon of Fascism, I can point to as many as three speeches I gave at the congresses in Moscow of 1922, 1924 and 1926. Here, I presented Fascism as but one of the forms through which the capitalist bourgeois State asserts its dominion, to be employed as an alternative to liberal democracy according to the needs of the dominant classes (parliaments being more useful in certain historical conditions to promote the interests of the bourgeoisie). The use of force and of police repression was dramatically exemplified in Italy by Crispi, Pelloux and many others, whenever the bourgeois state could benefit from trampling over the much-vaunted rights of freedom of propaganda and organisation. The often bloody historical precedents of these means of oppression prove that the recipe was not invented or pioneered either by the Fascists or their leader, Mussolini, but was much older. The text of those speeches of mine can be found in the proceedings of the world congresses, and will certainly be republished by our current in the future. Departing from the theories articulated by Gramsci and by the centrists of the Italian Party, we disputed that Fascism could be understood as a contest between the agrarian, land-owning and rentier bourgeoisie – on one hand – and the more modern, industrial and commercial bourgeoisie on the other. Undoubtedly, the agrarian bourgeoisie can be said to be connected with right-wing Italian movements, just as Catholics and clerical-moderates, while the industrial bourgeoisie was closer to the parties of the political left which used to be known as ‘the laity’. The Fascist movement was certainly not oriented against one of these two poles, but aimed to block the offensive of the revolutionary proletariat, fighting for the conservation of all social forms of the private economy. We steadfastly maintained that the real enemy and foremost danger was not Fascism, much less Mussolini the man, but rather the anti-fascism that Fascism – with all of its crimes and infamies – would have created. This anti-fascism would breathe life into that great poisonous monster, a great bloc comprising every form of capitalist exploitation, along with all of its beneficiaries: from the great plutocrats down to the laughable ranks of the half-bourgeois, intellectuals and the laity.

- In August of 1922 the was a last series of great strikes before the March on Rome. In that moment, with Fascism on the verge of seizing power, was the weapon of the strike still adequate to the situation? Did you still believe in the possibility of revolution?

I reiterate my historical assessment that the last clash between Italian proletarian groups and the Fascist squads – with the full backing of state powers – was the great national strike of August 1922. The Communist Party of Italy, both in its internal propaganda and in lively discussions at the international congresses, had already spoken against the strategy of forming a league among different political parties. We only accepted the hotly-debated stance of creating a single trade union front, while rejecting any political fronts or blocs. The main reason for this choice is that the latter would have required a supreme hierarchical body, to which the parties would have owed their allegiance. This carried the unacceptable risk the the forces of our party be compelled to act for objectives that contrasted with those dictated by our doctrine and historical vision, and that we could never relinquish. In Italy, while the political front would have led to the already rejected alliance with the reformist and maximalist parties, the trade union front could have accommodated the great General Confederation of Labour, alongside the Italian Workers’ Union (which had opposed the war) and the robust Rail Workers’ Union. The propaganda and organisational work required by this trade union front, which we called Labour Alliance, were already advanced by 1922. The political bloc would have led to a weak parliamentary grouping working towards the other strategic objective that we fiercely opposed in Moscow: namely, the ‘workers’ government’. The Labour Alliance, on the contrary, could have accommodated the rigorously revolutionary and Marxist methods of the general strike and the armed civil struggle to overthrow the power of the bourgeoisie, which was in the hands of the Fascists.

Going back to the chronicle of those tumultuous times, while all right-wing and opportunist elements pressed to form an alliance between the parties that we opposed, the Rail Workers’ Union convened in Bologna representatives from all parties and unions. The aims of this meeting were somewhat murky. To be consistent with our methods, we chose as our delegate the comrade in charge of overseeing the union organisations that belonged to our Party. This comrade brought back to us the stunning news that, wishing to avoid the strike, the largest organisation present at the meeting – the General Confederation of Labour – claimed to lack a communications network capable of transmitting the order to all participating Chambers of Labour. Faced with this disgraceful behaviour, our delegate – as instructed by the Executive – offered the use of our illegal networks (hitherto unknown to the state) for the transmission of the strike order, which the Confederation was asked to draft. The Confederation and the other participants accepted our offer, as none of the non-communist organisations could respond to that need. Thus, we made sure that even the remotest centres would receive the official order to strike, by mobilising our party and union network and throwing our full support behind the movement.

The strike gathered great strength throughout the country and was able to face down the harsh measures adopted by our opponents. Regiments of the carabinieri were deployed against the city of Ancona, while a whole division of destroyers lay anchor off the coast of Bari. The workers who occupied those cities responded with all the means at their disposal, while totally abstaining from work. This made it impossible to run the train network, which was essential for mobilising the military. The so called ‘cross-river’ proletarian suburbs of Parma rose up. (As is well known, that city is divided in two by the Parma, an affluent of the Po.) The Fascist forces sent to extinguish the insurrection were led by the famous quadrumvir Italo Balbo. Later, when Balbo crossed the Atlantic, the brave workers of Parma wrote in large letters on the banks of the stream the following taunt: ‘Balbo, you crossed the Atlantic but you couldn’t cross the Parma’. The breadth of the stream was enough to stop the anti-proletarian forces. This and other episodes demonstrate that the great strike movement was not only possible but also very effective. The Fascists, who could count on the support of the State and its armed forces, were unable to defeat it. The following October, when they mobilised to march on Rome, they didn’t prevail in battle, but thanks to a compromise that enabled Mussolini – wearing a tuxedo and a top hat – to make a peaceful entrance in the palace of the government. The King had taken back his declaration of a state of siege, against the counsel of his generals. These inglorious manoeuvres, strictly borne out of parliamentary politics, prevented both the real proletarian revolution and the faux revolution of the black shirts.

- At the end of 1922, at the Fourth Congress of the International in Moscow, you spoke against the view of the majority, of Zinoviev and of Lenin himself, claiming that it was neither useful nor just for the communists to attempt to merge with the socialists to create a coalition government. How do you explain this opposition to the amalgamation, given that the maximalists had already split from the reformists?

It’s true that at the time of the Fourth Congress in Moscow, in December of 1922, Fascism had already risen to power in Italy, and the Socialist Party – which represented the majority at the time it split from us in Livorno – had fractured into two parties, a maximalist one and a reformist one. The Congress in Milan saw the birth of another current, the so-called ‘third internationalist’, which supported re-entering the Third International by merging with the Communist Party of Italy. It is also true that the left communists and I rejected the amalgamation supported by Moscow, not only with the maximalists, but also with the terzini – as we called the new faction, which included Serrati, Riboldi, Fabrizio Maffi and others. We believed that the positions of Serrati’s party contrasted openly with all of the resolutions of the Second Congress and with the theses of the Communist International themselves, including those that hadn’t been accepted by our current – as in the case of the parliamentary question – as well as with the union, agrarian and national-colonialist theses, which we always supported. Consider again the position taken by the Socialist Party concerning the famous ‘peace pact’ with the Fascists and the events that followed, up until the great struggle of August 1922, as we discussed in some detail above. We strongly opposed the exhortations of our Russian comrades to accept a seat in the famous ‘Amalgamation Committee’ of communists and third-internationalists, which was also tasked to lead our future common electoral strategies in Italy. I believed then, as I still do now, that the eventual amalgamation didn’t bring to our party any qualitative or quantitative benefits in term of increased strength and influence. Nor did it help us withstand the attacks by the reaction, much to the disappointment of our Russian comrades – including, as mentioned in your question, Zinoviev and Lenin.

- Your abstentionism with respect to everyday political tactics has been accused of leading the Party to a state of inertia and paralysis. Why were you, Mr Bordiga, always against any action involving a common front or alliance between communists and the other parties that opposed Fascism? What is your assessment of the conduct of the anti-fascist parties in 1923 and 1924?

Abstentionism – which I supported along with the majority of the Party – did not mean abandoning everyday political action, but rather one of its technical and practical forms: namely, participating in elections and parliaments. By absorbing all of the energy and dynamics of the Party, this activity leads to neglecting other, far more vital forms of action for a class-based political party, including the open and – if necessary – violent struggle against the legal and illegal forces that defend the capitalist order. Abstentionism, then, was the true antidote against paralysis. What would have led to stasis was precisely forming coalitions with other parties, including those with whom we had broken our physiological ties in the field of organisation. These ties would return not in larval but rather pathological form, as an alliance that our followers and militant themselves could not have understood. To reiterate the fact that within our ranks there was great reluctance in becoming entangled in electoral and parliamentary manoeuvring, I’ll recall the fact that in early 1921 I had to publish in the Party press an article against the request by various base organisations to find and expedient capable of mediating between that reluctance and the duty to obey the decisions of the International. The conduct of the so-called anti-fascist, non-revolutionary Italian parties in 1923 and 1924 – especially after the murder of Giacomo Matteotti – was openly disapproved by myself and many other comrades, for it created the conditions for a collaboration between the workers’ movement and parties ideologically aligned with the bourgeoisie, such as the Catholic party and the liberals. This anticipated the politics that dominates the structure of the Italian government today and to which the Communist Party itself – far degraded from the high origins of the Livorno split and the struggle against all anti-Marxist and anti-worker compromises in the name of ‘democracy in Italy and Europe’ – aspires to rush into. It was I who, speaking legitimately for the left of the Party, suggested to Antonio Gramsci that the communists should abandon the simulacrum of parliament that took the name of Aventine Secession: this enabled us to make a number of speeches in the Chamber of the Deputies that drew Mussolini’s ire and called generously and courageously for mass insurrection. I’ll cite just those by Ruggero Grieco and Luigi Repossi – still available in the archives of parliament – which they delivered against the savage rabble of the Fascist members, who physically assaulted our comrades and chased them from the Chamber.

- Mr Bordiga, you took part in the Fifth World Congress of the Communist International in Moscow, in 1924, and delivered a lengthy report on Fascism in Italy. What were the basic ideas of this report? What was your analysis of the economic, social and political components of Fascism?

At the Fifth Congress of the Communist International, in Moscow, I delivered a thorough report on Italian Fascism that repeated some of the points I made at the Fourth Congress, soon after the March on Rome. At the time, I described its rise to power as a ‘political comedy’ as opposed to a ‘coup d’etat’ resulting from the clash of military forces. This is because the black shirts had not defeated the forces of the state in an armed struggle, for the latter failed to take advantage of the King’s call for a state of siege. For his part, Mussolini comfortably travelled from Milan to Rome in a sleeping car to meet the King, who had summoned him to the government’s palace. As for the social foundations of Fascism, I reiterated that – contrary to theory advanced by Gramsci – they did not lie in the class of agrarian land-owners, but encompassed instead the modern industrial class, while the Party cadres were recruited not only among the rich but also from the middle classes, including professionals, artisans and students.

- For what ideological and practical reasons did you refuse to advance your candidacy to parliament for the Communist Party at the 1924 elections? What were the consequences of your refusal within the Communist Party of Italy?

It wasn’t primarily for the ideological reasons deriving from my abstentionist battles that I did not advance my candidacy for the general elections of 1924, but rather for practical reasons. The names of communist candidates don’t arise out of subjective requests and personal initiatives, but are chosen by the Party through a body that evidently, on this occasion, chose not to put forward my name. It wasn’t a refusal on my part, then, although I certainly wasn’t displeased with their decision. This didn’t cause any particular damage to the party, although the centrist comrades of the leadership office objected that we would lose a seat in parliament. They thought that I would have been elected in any of the Italian constituencies, due to my notoriety and my skill as an orator and polemicist.

- What made you suggest that the communist members of parliament should return to the chamber after the Aventine Secession?

I already explained above, in my answer to the 14th question, that the Aventine Secession was a total capitulation to bourgeois and capitalist reaction. It justified our easy historical prediction – cited above – the the most sinister effect of the Fascist phenomenon would be the rise of the anti-fascist bloc, whose ambiguous politics was to become dominant and smother the future of our hapless Italian society, as we witness today.

- Why did you also flatly refuse the role of vice-president of the International which had been offered to you by initiative of the Soviet delegation? What would your taking this role have meant, and what would its consequences have been for the Communist Party of Italy?

I rejected without hesitation the offer made by Zinoviev to become vice-president of the International, above all because I couldn’t give up my struggle against the alliancist and united-front politics favoured by Zinoviev himself, which I had opposed at all previous congresses. Moreover, I knew quite well the internal issues of the Russian Bolshevik Party, and understood that Zinoviev would soon be removed from the role of president by order of the Stalin’s group, which had become dominant. He was to be replaced by Bukharin, who was faithful to Stalinist politics. During my work in Moscow and after a lively discussion within the Italian Committee between myself and Stalin (which was later published by the Annali Feltrinelli, based on the documents held at the Tasca archive), at the time I may have been the only one who understood that Stalin’s repression would have doled out the same treatment to Trotsky as to Zinoviev and Kamenev. These two, who were initially distant from Trotsky, sympathised with him during the debate at the November 1926 meeting of the Expanded Executive concerning the disastrous ‘Socialism in One Country’ formula. Even earlier, when I was offered the vice-presidency, I knew that it would have become the hot battle ground of the desperate struggle to prevent the fall of the Communist International of Moscow into the abyss of a new – and worse – kind of opportunism, which my current and I foresaw.

- How do you explain, in 1925, the ideological agreement between Antonio Gramsci and the liberal Gobetti on the basis of the common struggle against Fascism.

Concerning the relationship between Antonio Gramsci and his friend Piero Gobetti, editor of Rivoluzione Liberale, I can tell you that I talked to Gramsci about this once. ‘Antonio,’ I asked him, ‘I need you to do me a great favour. Please find me a complete collection of Gobetti’s magazine. I want to subject it to a close analysis and critique from our point of view of revolutionary communists.’ Antonio understood that my intention was to demonstrate the impossibility and danger of waging a campaign against Fascism alongside an avowed liberal such as Gobetti. With his best smile, which lit up his expressive blue eyes, he immediately replied: ‘Please don’t do this, Amadeo, I’m the one asking the favour.’ I confess to have acquiesced to that tacit, friendly request, and that I never wrote what in journalistic parlance would have been a savage review of revolutionary liberalism. Gramsci’s willingness to work with Gobetti can only be explained through the tactics that he had mistakenly embraced. He thought that it was possible to form alliances with any of the adversaries and critics of Mussolini in preparation for a future Italian regime, a theory that I notoriously abhorred – as I do to this day. The friendship as well as the comradeship that always linked me to Antonio – whom I admired greatly – never faltered. The last time we operated together in what can rightly be called a party environment dates back to 1926, when both of us were sent in confinement to the island of Ustica. At that time, whenever the discussion among fellow confinees touched upon a problem concerning our principles and our movement, Antonio and I, as if by tacit agreement, offered to explain to the audience each the position of the other. Obviously, neither of us meant to diminish his objections to the thinking of the other and of his current. The double explanation ended typically with a reciprocal confirmation that each had correctly interpreted the overall ideas of the other. Clearly, it was a double and incompatible historical vision: Gramsci’s clearly anticipated the line of the future Italian anti-fascist bloc, while I opposed it as resolutely as I could.

- At the Congress of the Communist Party held in Lyon in 1926, you were outvoted and the leadership of the Party passed on to Gramsci. To what extent was that defeat premeditated and willing? Is it true that your disagreement with Gramsci concerned above all his assessment of the Italian situation?

It’s true that, at the clandestine Congress of the Communist Party of Italy held in Lyon in February 1926, our Left current was defeated by the centrist current of Gramsci and Togliatti. It was not a clear and unambiguous defeat, not even in terms of the internal party democracy – a method which we never acknowledged. It was therefore a defeat we neither acknowledged nor accepted. As explained in the appeal we immediately lodged with the Executive of the Communist International in Moscow, the supposed consultation with the base of the Party had taken place in a manner that could only be described as questionable and suspicious. Every member who turned out not to have voted either for the line of the Executive or the Left (the latter of which had been clearly formulated in articles and resolutions in the Party organ, Stato Operaio, throughout 1925, although by my initiative we had dissolved the Entente Committee, which was formed by a group of well-known leaders of the Left current, and immediately charged by the Executive with the unjust accusation of attempting to fracture and split the party) – all those members, I say, who did not formulate any opinion or decision, should not have been included in the vote for the congress, but were added instead, by express deliberation of the Executive, as having voted in support of its own conduct and programme. It is hardly necessary to point out that Moscow did not even consider our well-founded appeal. Victory was therefore handed to the centrists and Stalinists. Gramsci, Togliatti and their friends were fully endorsed as leaders of the Italian section at Stalin’s behest. No weight was given to our legitimate complaint that there is no sense in asking for consultation – as a semblance of internal democracy – in a party that operates and convenes its local branches or federal congresses under the crushing weight of the poisonous Fascist dictatorship.

My dissent with Gramsci, as it should be clear from many of the considerations I have made so far, was not concerned primarily with the assessment of the Italian situation, but rather on its possible developments in the near future. I took issue with the view held by Gramscians that a bloc of anti-fascists of all hues – either after the fall of Fascism or as a result of an internal crisis, as it was later the case, or due to the international consequences of the war – could have created a government based on a democratic constitution to regain control of our vanquished and no longer governed country.

- In the early years of the Communist Party, there was a significant degree of political convergence between you and Gramsci. However, after 1922 a rift started to form, culminating in your expulsion from the Party, in 1930. What was the reasons for this rift? And what were the reasons for your expulsion?

There was a significant convergence between Gramsci and me in the period that led to the creation of the Communist Faction within the old Italian Socialist Party, and after the split in Livorno and the foundation of the Communist Party of Italy. At this time, we worked together to implement the directives and the actions decided upon in the first congresses of the Communist International. This convergence was the result of our shared opinion on the historical course of the parties of the Second Socialist International, which came to harbour – as we used to say – two souls: a revolutionary one, and a reformist or gradualist one. Gramsci and I, together, believed that this contradiction could only be resolved by separating the old militants into two distinct organised movements.

In 1922, I thought that this split should be followed by a phase of open struggle, even war, between the party that aimed to foment a cataclysmic revolution in order to destroy the capitalist social order and the others, which believed it possible to use the legal means the bourgeois regime gave to its own enemies in order to correct it through a slow evolution and transformation of its internal structures, without recourse to violent or adversarial means. Gramsci’s thought, instead, went through an evolution (or perhaps an involution) concerning the dynamics that led to the birth of new class parties from the ashes of the traditional ones. Since it was clear that each of the parties that emerged from the split could count, quantitatively, on a smaller support than before, he began to accept the idea that it would be best to for the two structurally detached wings to form a common front or bloc, using both legal and illegal means. This historical formula, which I have always regarded as arrant nonsense, was articulated in this rather inelegant phrase: ‘March apart, strike together.’ Gramsci believed that our party would have been much stronger had we accepted to form an alliance with the Socialist Party or even just with its robust left-wing, as suggested by Moscow. This, in my opinion, only goes to prove that Moscow was already deviating from the right revolutionary path dictated by Marx and Lenin. In the historical sequence of the episodes that provide the context for these questions and answers, we have already touched upon many of the issues on which Gramsci’s opinion and mine diverged. However, all our disagreements originated from a single dispute on the ideological and – I’m tempted to say – philosophical basis for the breaking out of class revolution. This is what I told Gramsci at the Congress in Lyon during my seven-hour speech (he had spoken before me, for nearly as long). Both of us described in great detail the solutions we advocated to the problems facing Italian communists in their various fields of activity. At the end of this exchange, I turned to Antonio and told him that one has no right to call oneself a Marxist, nor a historical materialist, just for accepting certain thesis as the baggage of one’s party – whether they concern trade union or economic action, parliamentary tactics, or questions relating to race, religion, culture. Rather, marching together under that political flag requires sharing the same fundamental ideas about the universe, history and the role of humanity within it. It was many years ago, but I recall with certainty that Antonio said he agreed with my formulation of that fundamental conclusion, and admitted in fact to have only just glimpsed that important truth. I do not offer this objective account of the relationship between Gramsci and me as a way to explain my expulsion from the party, therefore from the Communist International, to which your question refers. This was to take place in 1930. At the time, I had been freed from the police confinement ordered by the Fascists. The only news I received of the expulsion came from the mainstream press, which stated as the reason my refusal to travel to Moscow for a new congress. I had no medium with which to defend myself from that accusation. At any rate, I said then and reiterate now that neither the Committee in Moscow nor the Italian party ever extended me that invitation. Had the invitation reached me together with the practical means of accepting it, just as in Lyon – in agreement with all my comrades of the left current – I had refused to be included in the leadership of the Italian Party (as testified by a very harsh final statement that was read out at the Congress), so too I would have rejected the invitation to go to Moscow. The Sixth Worldwide Communist Congress was held in Moscow in 1928, and I didn’t take part in it. I later learned that, at the behest of Stalin, a new political tactic was adopted, concerning what came to be known as ‘social-fascism’. It was decided that all Fascist and social-democratic parties should be considered enemies of Moscow and of Communism. This was an abandonment of the tactic of the united socialist front. Later, in the official communist press (and after the well-known expulsion of the three Italian dissenters Leonetti, Tresso and Ravazzoli), came the admission that the tactic had been advocated ahead of time by left Italian communists. I wrote it in an article as early as 1921: ‘Fascists and social-democrats are but two aspects of tomorrow’s single enemy.’

- Mr Bordiga, you have been accused of showing little flexibility, of being incapable of adapting action to the circumstances, and of having a tendency to form ‘revolutionary sects’. How do you respond to these objections raised by Lenin and others at the Congress in Moscow?

Were it credible for me, all these years later, to formulate a historical assessment of my own qualities and qualifications, I would say today that I’m glad to be labelled a sectarian, and that I agree that I was never adaptable, nor easily persuaded by those who advocate flexible solutions to the changing political conditions and the shifting balance of power between the social classes. I’ve been frequently accused of being too sectarian and inflexible, but it has never made me waver from my path, which I have followed with total conviction. At the congresses in Moscow, these accusations were never made by Lenin, but rather by his many slavish imitators, who were certainly willing, but always fell short of capturing the brilliance of his thought. I believe I gave a good account of this in my piece on Lenin’s extremism, and on the false speculations made after his passing by those who betrayed his thought (it was published along with the text of the eulogy I gave in Rome in 1924, under the common title ‘The Italian communist left on the Marxist line of Lenin’). While it’s correct to believe that the great class revolution can’t be sparked by a banal conspiracy – unlike those that merely aim to replace one group or supreme leader with another – we must also acknowledge that it is preferable for the class party to assume the iron-clad form of the sect, instead of diluting the strictly disciplined relationship of its centralised organisation – as devised by Lenin – in an ambiguous one. The latter form enables elements or rank-and-file groups to freely experiment and carry out undisciplined and improved actions in the name of the whole party, as those who possess political agility are prone to seize false opportunities dictated by new facts and developments – real or imagined. That is to say, it replaces the inflexible commitment required of the militant revolutionary with a series of acrobatic exercises deserving of the sneering expression ‘going for a waltz’. It would be an offensive parody to the memory of the great Lenin to confuse the respect for tactical flexibility with such deplorable circumstances, which only hapless and obtuse students could attribute to that incomparable master.

- Another accusation that followed you all your life is that your considered political struggle in abstract terms, adopting a scheme of thought that became known as ‘doctrinarian schematism’. This, according to your critics, would have led you to commit grave mistakes. To what extent do you think today that this analysis is legitimate? Or do you reject it outright?

I totally reject the so-called analysis on which you based your 23rd question, which doesn’t reflect the construction of my thought nor my decision to enter the political and social struggle. Besides, it is objectively incorrect. When you subscribe to a class movement or to the theory of it magnificently developed by Karl Marx, the classes that clash against one another (nowadays, the capitalist bourgeoisie and the salaried proletariat) should not be reduced or represented – in order to reproduce their dynamics and antagonism – as concrete categories, but rather as abstract concepts, referring to experimental social facts. Abandoning the imperative of abstraction in order to replace it with the easier and smoother concretism is at the root of the disastrous mistake made by those who – in spite of having become, in a Marxist sense, the ‘traitors’ of their class or, to use the Leninist formula, the ‘professional ranks of revolutionary struggle’ – vied to become the leaders of the national and international proletarian movement. If I had any virtue, it was to remain entrenched on the side of abstraction, which I believe to be necessary for reasons intrinsic to the physiological life of the movement and the propaganda and agitation that form its backbone. I also believe that those who fill their mouths with the insidious term ‘concretism’ did so for reasons of opportunism (which had the better of us in 1914), breathing new, diseased life into this cancer that saps human history and our revolutionary energies. Having made these clear distinctions, I think I can rightly state that the transmission and re-transmission of a solid doctrinarian schematism between the leadership and the base is an irreplaceable element of the life of any communist party, and an essential weapon in the struggle against the degeneration of the worldwide revolutionary movement. I’m proud to say that this is the task to which I have dedicated my not short life.

The text of the interview was originally published in Storia Contemporanea no. 3, September 1973. Bordiga also spoke to journalists Sergio Zavoli and Edek Osser for a filmed interview, excerpts of which were included in a documentary on the rise of Fascism.

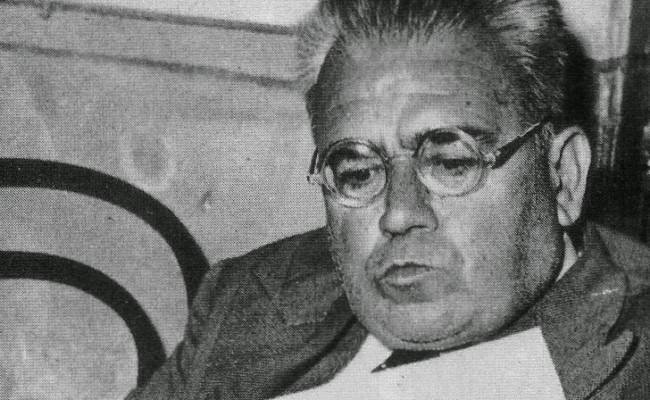

Image: Amadeo Bordiga