Mangatjay. Dhuwal ngarraku yäku. Dhäwu ngarra dhu nhukal lakaram. Ngarraku dhäwu – Mangatjay. That is my name. I’m going to tell you a story. My story.

My history

Milingimbi is part of the Crocodile Islands of north-east Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. Being born to a Caucasian (British, Scottish background) father and a Greek-Aboriginal mother meant that I had a mixed upbringing. My Momu and Märi’mu (paternal grandparents) did most of the child raising.

Momu is this highly intelligent, well-educated woman who taught me that a quality education is the single most powerful tool you can have in your arsenal. Märi’mu is this genuine, down-to-earth man (with a cool outback Aussie accent FYI), who imparted in me a sense of community and humanitarianism. They have the most generous of hearts.

In our household there were seven people – Momu, Märi’mu, my aunty, my two uncles, my cousin and me. This number fluctuated over time – sometimes my mum and dad would live there, sometimes a cousin, sometimes another aunty – so there could be up to ten or eleven people in the household, but they always made it work. My grandparents are very accommodating people. If somebody in the community needed help, they were there by your side.

They probably don’t realise this but they are my heroes.

Community life – the Yolngu way

It was a fun time in my life, living on the island. Milingimbi has a population of just over one thousand (less when I lived there), so you got to know most people in the community rather well. One of my fondest memories is of coming home from school and playing in our enormous backyard; children would come from all around the island to play basketball and soccer there. Sometimes we would play until the sun went down.

My group, the Yolngu people, is lucky enough to be one of the least impacted by the invasion process. We still retain a strong recall and practice of Ngärra (traditional) law, language, kinship, hunting and gathering, and other customs.

The local school, Milingimbi CEC, had a bilingual program where we were taught in English and Yolngu Matha. At school, we learnt various aspects of Yolngu culture; particularly important was knowledge of the seasons. People tend to simplify the seasons in the top-end of Australia to wet and dry. For us, the concept is more complex: the year is broken up into six seasons, which governs when we harvest certain plants and hunt for different species of animals. Yolngu people respect the land that they live on and in return it looks after us by providing invaluable resources. Being taught this traditional Yolngu knowledge cemented my identity.

These memories and experiences are my roots, a solid foundation from which I continue to grow.

Being fair-skinned and Aboriginal

So anyway, I’m this light-skinned, blue-eyed guy – hardly the image people have in their minds when they think about what an Aboriginal person looks like.

This has been a double-edged sword. I’m proud to be an Aboriginal man. My family upbringing fostered a strong sense of self and pride. It’s the outside noise that’s the problem. On numerous occasions, it has led me to question whether I have a place in this world.

Living on Milingimbi was not without challenges. Where I come from the vast majority of the population is Aboriginal (Yolngu people), with typically dark skin. Most of the community accepts that I am Aboriginal. But others found it hard to believe. I have distinct memories of times when other children would call me ‘coconut’, a term targeted at mixed race people who are deemed ‘too white to be black or too black to be white’, as if to imply that all mixed race people strive to embody either a white or black way of life, and that both are mutually exclusive. This is a classic example of lateral violence, whereby members of a marginalised group participate in harmful actions directed at other members of the same group.

Being fair-skinned and Aboriginal means your Aboriginality is always in question. I have encountered this problem irrespective of where I live in Australia. It’s happened in Darwin; it’s happened in Adelaide; I’m sure it will continue to happen. There are people who cannot fathom the idea that you can be Aboriginal and have white skin, and of course there are all the negative stereotypes and racism that permeate our day-to-day existence. One of the most prominent examples was in 2011 when Andrew Bolt was sued, after writing two articles, ‘It’s so hip to be black’ and ‘White fellas in the black’, in which he claimed that a number of high-profile people identified as Aboriginal purely for personal gain and political traction.

Recently, journalist Laura Murphy Oates wrote of some of her experiences as a light-skinned Koori woman. It has led to ‘some interesting situations’, Laura observes. Being able to blend in means that non-Aboriginal people become particularly honest with their views about Aboriginal people. Nowhere was this more apparent for Laura, than on her recent trip to Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, for the one-year anniversary of Elijah Doughty’s death. There, a young mother told her the government needs to intervene because Indigenous people are bad parents.

Only days following the one-year memorial, a local non-Aboriginal man divulged to Laura over the phone that he had tried chasing down children in his car, as he thought they had stolen his motorbike. He wanted some ‘Kalgoorlie justice’; online he declared that children who steal ‘deserve to be run over’.

But this racial divide is not unique to Kalgoorlie. These views pervade other areas of our country. On numerous occasions I’ve had people make racist jokes or comments in my presence with a disgusting look of satisfaction on their faces. I’ve even witnessed patients (I’m currently a medical student) make demeaning, racist remarks about Aboriginal people. I’m sure it never crossed their mind that I have Aboriginal heritage.

If I don’t identify as Aboriginal, sure I can hide behind the privilege a lighter skin colour affords you, but then I’m not acknowledging an integral part of my identity. It’s a case of damned if you do identify as Aboriginal and damned if you don’t.

I’ve also experienced numerous racist and belittling remarks in the gay community, and been turned down for dates, especially on online networks such as Grindr, simply because I am Aboriginal and proudly display that fact. This makes you feel like a cultural misfit. Where do I turn to if I’m shunned by each demographic where I have sought acceptance? What if I never fit neatly into Western, Aboriginal, or gay culture?

Dennis Foley explores this perspective in his paper ‘Too White to be Black, Too Black to be White’. Fair-skinned Aboriginal Australians are afflicted with a sense of not belonging, he explains, and are exposed to constant interrogation of their Aboriginality, leading some to no longer identity as Aboriginal for self-preservation.

Perhaps I need to create my own culture, a space where I can embrace both my Aboriginal and Euro-Australian heritage. I challenge you, dear reader, to live beyond a lens shrouded in stereotypes. Break the stereotypical mould of what an Aboriginal person looks like, behaves like, lives like.

Some of us are black and living on communities, some of us are fair-skinned and living in cities, others are somewhere in between. We are just as diverse as people belonging to any other culture. Why is that so hard for some people to understand?

If you think you’ve never met or seen an Aboriginal person, the chances are that you have but you didn’t realise it. It could have even been me.

I’m Mangatjay. This has been my life as a light-skinned, gay, Aboriginal man.

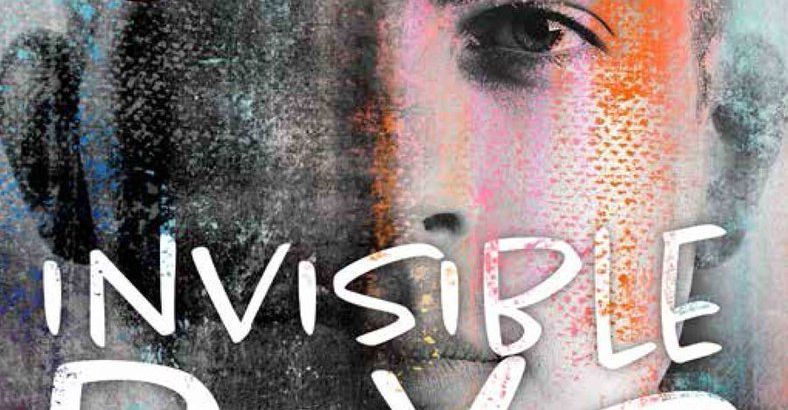

Image: aerial view of Milingimbi