When the ‘no’ campaign for the marriage equality postal survey launched its first television advertisement, the strategy was clear – it aimed to deliberately associate the ‘yes’ campaign with gender diversity, queer families, and the Safe Schools program. In the ad, to a soundtrack of menacing piano music, concerned mothers ask us to imagine a future of teachers telling boys they can wear dresses if they want to, and kids role-playing gay or lesbian relationships.

The ad was funded by the Coalition for Marriage, the campaign front group for the Australian Christian Lobby (ACL). Their campaign strategy of tying marriage equality to gender comes as no surprise. 2016 saw the ACL and Murdoch press band together to stir up controversy about the Safe Schools program, based on false claims of parental complaints. The media attack focused largely on a battle against what they termed ‘gender theory’ – the idea that gender is a social construct and that sexuality is fluid.

The right’s crusade was largely successful. Despite the fact that it was Tony Abbott himself who signed off on the original Safe Schools funding, all Federal money has been removed for the program. Victoria is still supporting the program, but has taken control from the hands of the original creators. NSW has officially eliminated ‘gender theory’ from the classroom, a decision that followed their decision to ban the screening of the queer family documentary, Gayby Baby.

This incitement to fears about ‘gender theory’ has been exhumed in the marriage equality debate. On Sky News recently, Coalition MP Kevin Andrews explained why he would be voting no in the postal survey: ‘[what] is being advocated increasingly through things like the Safe Schools program … [is] there being neutrality or fluidity in relation to the way in which people identify with different genders … this is a pathway which will lead to anybody claiming whatever gender they like.’

Similarly, other government ministers – notably Abbott and Eric Abetz – have argued against marriage equality on the basis that children ought to be raised by a mother and a father. Abbott even suggested that the children of his lesbian sister would be better off being raised by a heterosexual couple. The right’s defence against marriage equality is in fact about protecting traditional gender roles within a nuclear family unit.

But while the right’s response to the postal survey has been somewhat predictable, what has also been hard to watch is the response of some in the ‘yes’ campaign. Despite the unfolding homophobia and transphobia around the postal survey, it is clear that groups like Australian Marriage Equality and GetUp have decided to steer away from these topics. Rather than defend trans people, Safe Schools, and queer families, these groups have rolled out doctors and heterosexual families to provide reassurance that marriage equality does not involve a gay agenda of radical ‘gender theory’.

One group even made a ‘humorous’ parody of the ‘no’ ad, likening boys wanting to wear dresses to children wanting to become birds. Rather than confronting the transphobia of the original ad, the satire portrayed the issues raised as utterly ridiculous and unrelated to marriage equality. It is deeply disheartening and distressing to see the ‘yes’ campaign sideline respect for trans and gender diverse people as irrelevant, when ‘no’ campaigners are so clearly targeting questions of gender.

One of the key arguments of the right is that marriage equality has contributed to the recognition of trans rights in other countries. For example, the UK is currently considering updating their Gender Recognition Bill, a set of reforms that would bring them well ahead of Australia. Ireland took a similar route after their referendum on marriage equality. That winning rights for some in the LGBTQI community might help to open up space for greater recognition more broadly ought to be celebrated and defended. If we do not take up this position, and indeed if we undermine the solidarity of the LGBTQI community through isolating issues and excluding some, we limit the possibility to win necessary reforms into the future.

Indeed, the myopic strategy of parts of the ‘yes’ campaign does more than forgo recognition of gender diversity. To see this current marriage equality debate as relating to marriage alone imprisons us in a restrictive straightjacket fantasy of the white picket fence.

To ignore the homophobia and transphobia that has already been unearthed in this debate, and to focus on marriage and romantic same-sex weddings alone, paves the way to hollow victory. Such a campaign can make only a limited dent in in the violent and restrictive beliefs of the right, that have already done real damage to programs like Safe Schools. The right’s focus on gender should be taken as a hint that there is more to win – and indeed more to potentially lose – in this campaign.

The right is afraid that with a loosening up of whom one is allowed to marry or pair with, so to will there be a relaxation in rigid gender roles. Infamous gender theorist Judith Butler would agree with this assertion, though not the right’s homophobic conclusions.

In her classic text Gender Trouble, Butler illustrates how the expectations of gender are bound up with sexuality. She describes this set of expectations as a ‘heterosexual matrix’ whereby one’s physical ‘sex’ must line up with one’s gender and desire. So for example, if a penis is identified at birth, one is proclaimed a ‘boy’ who must grow up to be masculine man, who must be attracted to women.

We assume that these connections are natural rather than related to social and cultural expectations. Butler suggests that because of the intimate connection made between sex, gender and sexuality, when we question heterosexuality there is also ‘a crisis of gender’. In other words, to deviate from this set of expectations is to upset an entire normative chain.

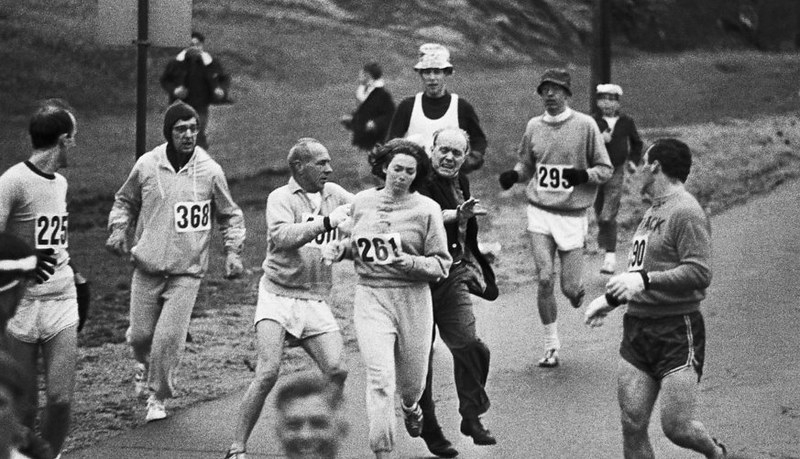

Preceding Butler’s insight into the social connection made between gender and sexuality was the Gay Liberation movement of the 1960s and 70s. During this period police frequently targeted gay bars, arresting people under ubiquitous cross-dressing laws that dictated what clothing one must wear. Often this involved having to have three pieces of clothing on to ‘match’ one’s assigned gender. After a group of patrons – led by several trans women and drag queens – rioted against a police raid at the Stonewall bar in New York in 1969, Gay Liberation was born. In the beginnings of this movement, a sexually and gender diverse group rallied together under the idea that ‘gay power’ could be revolutionary. Activists such as Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson were key to this new era. We ought not forget that those who paved the way for the LGBTQI freedoms we enjoy today were also gender revolutionaries.

A leaflet put out by the first Gay Liberation group in New York explicitly rejected gender roles, arguing: ‘We reject society’s attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature. We are stepping outside these roles and simplistic myths. We are going to be who we are … society has fucked with us.’

Gay Liberation explicitly rejected the more conservative lobbying tactics of their predecessors, who had focused predominately on law reform. These groups, known broadly as the ‘homophile movement’, often argued that homosexuals were innately afflicted and thus deserved sympathy, or that their sexual and gender proclivities were a wholly private matter. Members of the Mattachine Society in New York – a 1950s homosexual rights group – always made a point of wearing gender-appropriate clothing so as to appear respectable to their adversaries and general public alike.

Seeing marriage equality ads in recent times that suggest the central issue is one of ‘fairness and kindness’ can’t help but elicit echoes of the homophile movement. Rather than take inspiration from this more conservative era of activism, we should instead look to the rebellious and radical period that followed, which ushered in an entirely new focus on real, thorough liberation for LGBTQI people.

When the right sees a threat to normative expectations of gender and sexuality, we ought to embrace this – and see that a challenge to one link in the chain is indeed a challenge to another. As part of this, we need to make the fight against homophobia and transphobia central and confront these attacks head on. We need to embrace the possibilities for thinking about gender and sexuality more broadly in the debate around marriage equality, and open up space for including the diversity of LGBTQI community in our fairer and kinder world.