When we hear the word ‘critics’, the implication is that we are talking about literature; their lowbrow cousins warrant clarifiers, such as ‘film critics’ or ‘music critics’. In Australia, film critics are effectively quarantined from most major writing grants and arts funding for nonfiction or criticism – they are politely fobbed off to screen industry bodies who (at best) politely bounce them back. Alongside a number of other factors, professional film critics in this country risk becoming considered little more than dedicated hobbyists, something addressed recently by Cameron Williams.

Matters are, of course, further complicated for women film critics. Over recent years, increasing attention has been placed upon the inequalities that have marginalised women in the film industry. The success of Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook in 2014 and the 2015 launch of ‘Gender Matters’ (a $5 million initiative by Screen Australia to focus on women-led projects) has meant that in Australia, at least, awareness of gender disparities in the film industry is growing. Similar imbalances among critics and writers has also been a growing subject of interest. In late 2015, two influential articles were published in The Atlantic and Variety respectively, the former asking in its title: ‘Why Are So Few Film Critics Female?’

A June 2016 report from the Center for the Study of Women in Television & Film at San Diego State University, led by Dr Martha M Lauzen, noted that:

– most of Rotten Tomatoes’ ‘top critics’ were men

– male film critics outnumber women film critics

– male film critics are more likely to belong to a professional organisation

– male film critics publish more reviews than women film critics

– women film critics tend to review films with women protagonists more than men do, but gender does not appear to affect the ‘quantitative ratings’ of these films.

From an Australian perspective, this recalls the important work of The Stella Count, which – in the case of literary criticism – seeks to ‘assesses the gender of authors reviewed, the gender of reviewers, the size of reviews, and the genre of reviews – and examines the ways these aspects intersect in review coverage.’ But there is no Stella Count for film criticism; instead, the women film critics I know employ a less formal and statistically rigorous response involving pinot noir, vented spleens and a high volume of f-words.

But there are some indications that similar gender gaps exist here: despite impressive efforts to include emerging critics of both genders into their ranks, the good people at the Australian Film Critics Association (of which I am a proud member) have yet to reach even close to parity. Of the 103 members publicly listed, only 36 are women. I note this not to have a go at AFCA specifically, but rather to suggest that some of the trends noted internationally are also reflected in Australia.

For all of these reasons, the itchy researcher in me began asking questions about the history of women’s film criticism in Australia. I was curious about the historical dimension to this issue, marked notably by the shift in dominance from print to online film criticism publications around the late 1990s/early 2000s. This shift occurred at the end of a genuinely astonishing, hugely successful burst of women’s feature filmmaking in Australia, a moment of our cultural history I have lovingly documented at my website Generation Starstruck. Through a research fellowship with the AFI Research Collection housed at Melbourne’s RMIT University, I began to dig into the historical status of women film critics in this country in order to provide some grounding as we try and get perspective on where we are today.

In order to paint a broad picture of the pre-internet climate for women critics, I immersed myself in a range of Australian film magazines published between 1980 and 1999. As Adrian Martin wisely reminded me in an email, these weren’t the only outlets for women writing about film in Australia, and to focus only on these publications should not diminish the range of other avenues – exhibition catalogues, zines, local papers, etc. – that were available to women film critics. Additionally, it seems somewhat naïve to make judgements on the role of women in the Australian workforce more broadly (let alone in journalism or film criticism specifically) considering the huge cultural and economic shifts that were occurring in the country that saw so many women leaving their traditional ‘housewife’ roles and returning to the workplace. With this in mind, however, these publications still have much to tell us, not only about women’s film criticism then, but also now.

The main publications I looked at were Cinema Papers, Metro Magazine, Freeze Frame, The Video Age and Encore!. These differ notably in tone, mission and audience, the latter spanning from industry to casual consumers to active cinephiles to academics and teachers. But I noticed a curious trend: while women film critics during this period were nowhere near as equal in number as their male counterparts, there was on the whole no dramatically striking imbalance in the relationship between the gender of critics and the gender of the directors whose films they discussed. On average, and in many of these publications I found, men were often just as likely to write reviews, interviews and features about films made by women as women film critics.

Before getting too excited, however, it is crucial to also note that this was a period where there were notably more full-time, career film critics (rather than freelancers, which in Australia at least is now surely the dominant norm): regardless of gender, in terms of a 9–5 job you would simply be reviewing the films that were on release – and Australia in the 1990s, as Generation Starstruck documents, was a boom period for women’s filmmaking.

It is also worth noting that articles about gender, and industrial aspects such as funding or broader issues of gender politics, certainly tended to be the terrain of women writers (with a few notable exceptions).

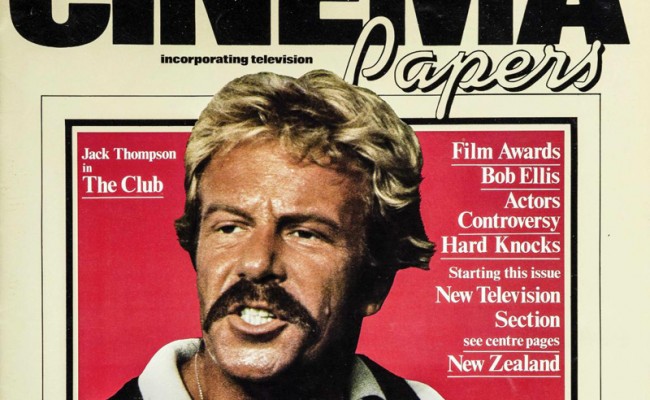

Clearly, there are imbalances facing women film critics in Australia both historically and in the present moment that warrant further discussion. But this observation aside, these publications provide fascinating insight into the film critical ecosystem of the period and the place of women writers within it. Of the publications I examined, the one with the most mainstream reach was probably Cinema Papers, which ran (intermittently at first) from 1974 to 2001. As I have noted in a recent article on the publication and its impact on me as a burgeoning film critic, as interesting as the data about women’s film writing and women’s filmmaking is, just as significant to me on a personal level were the women who were such a strong part of the publication’s history (particularly Philippa Hawker).

But the numbers pertaining directly to who wrote for Cinema Papers are in themselves of note: from May 1986 to June 1999, of the 1077 total contributors I counted, 341 of these were women. Of the 653 features (articles and interviews) I counted between February 1980 and June 1999, 81 were specifically on women subjects (not only directors, but producers, cinematographers, actors, etc.). In an ongoing critics poll that ran from May 1989 through to June 1999 under a variety of names (‘Dirty Dozen’, ‘Critics Best and Worst’, etc.) the only woman critic out of nine to twelve critics polled was The Bulletin’s Sandra Hall (who was later joined by Barbara Creed – then film critic for The Age). Of the 1018 films I counted that were polled from May 1989 through to June 1999, just 93 were made by women (Australian or otherwise).

Focusing on what was then the dramatic rise of VCRs in Australia, The Video Age magazine ran from 1982 to 1986, and – as the numerous softcore photoshoots for their ‘special issues’ on VHS pornography demonstrate all too readily – was a distinctly blokey affair. While the names of some of the male contributors were sometimes unexpected (George Negus wrote a piece in an early issue, and old mate Graham Kennedy ran a regular ‘letters’ column), women writers barely made an appearance beyond subjects clearly deemed to be ‘feminine’ terrain, such as soap operas and other things ladies like (Carol George had a regular celebrity gossip column, Jill Morris had one on kids’ movies). But The Video Age comes a cropper most spectacularly on the gender politics front through its use of language: many profiles of successful women in the industry swing between patronising and flat-out sexist, with titles like ‘The Highly Combustible but Very Friendly and Adorable Sig Thornton’ (March 1983) and ‘The Eminently Watchable Ms. Dunaway’ (February 1984). A feature on Jennifer Beals in July 1984 called ‘Not Just a Pretty Face’ was accompanied by a cover headline reading ‘That Flashdance Girl!’, and in June 1983 they spoke of Greta Scacchi as ‘a schoolgirl in Perth only six years ago, a beautiful blonde … now’.

Another contrasting aspect of Australian print film criticism of the 1980s and 90s is illustrated by the still-running Metro Magazine, which began publication in 1968. With a strongly academic and educational slant, Metro was notably progressive with its gender politics. From the Summer 1980 issue, women were heavily involved in Metro, with Helen Kon as associate editor under Peter Hamilton, and Trisha Nilvor as subeditor. In that issue in particular, five of its eight contributing editors were women, and of the eleven features listed, six were written by women. While on close inspection there is certainly more men writing features and longer-length pieces during this period, there is no specific gender bias in their subject matter that strikes the eye – male critics seem just as interested as their female counterparts in gender issues and the work of women filmmakers. Also of note is the incorporation of younger writers in Metro’s history, linked no doubt to the mission of their publisher, the Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM): one memorable instance is a 1984 interview with John Hurt by then-Year Ten student Fiona Kieni. But it’s who’s driving Metro during the 1980s especially that is perhaps the most interesting aspect: after a long run with Kon in the editor’s chair, Sheila Allison took over in the mid-1980s until the Autumn 1989 issue, co-edited by Peter Tapp and Philippa Hakwer (Tapp flew solo from Spring 1989 on, and remains managing editor today).

There were, of course, other publications during this period in Australia, including the short-lived Freeze Frame and Encore!. Freeze Frame ran throughout 1987 with Debi Enker as editor, a thoroughly sensible publication that – despite clearly reflecting a broader industry (and culture) weighted towards male critics and subjects – included Mary Colbert’s impressive feature on Gillian Armstrong’s High Tide in July 1987. Beginning in the 1980s, Encore! – a trade publication – is more an industry newsletter than glossy magazine, but during much of this period the standout name is woman critic and editor Sandy George, who is still a highly active and influential Australian film journalist and screen industry data analyst.

It remains unclear whether the rise of the internet as a primary arena for film criticism in Australia has influenced or altered the way that Australian women film critics have traditionally been positioned. What is most striking to me, however, is how so many of the strong critical voices from then are still around: women may not have dominated Australian film criticism historically, but they have absolutely persevered. Debi Enker, Sandy George, and Philippa Hawker – among many, many others – should be revered as professional trailblazers just as much as someone like Margaret Pomeranz.

But at its core, the issue then – as now – remains one of balance. Film criticism in Australia is typically separated in arts funding terms from what is clearly considered ‘proper’ or ‘real’ criticism (read: highbrow, literary). That the field itself is struggling to maintain its professional credibility is precisely why now is the time to look back at the history of film criticism in this country. This is even more urgent for women film critics, whose further marginalisation is now a documented fact. We need to look back and remember what worked and what didn’t in order to mobilise the field for a future profession strong enough to both nurture emerging critics, and to keep food in the mouths of those of us who are a little more established.

The research for this article was undertaken as part of an Australian Film Institute Research Centre Fellowship.

Image: Crop from Cinema Papers 29 (October–November 1980)