The roots of the crisis

François Hollande’s five year term as president of France was more than underwhelming, which largely explains why the recent election has seen France’s Socialist Party wiped off the electoral map. During a period of high unemployment, Hollande’s government conducted an aggressive winding back of the country’s labour code – their El Khomri Law gave individual companies more power over workers with regards to hiring and firing, pay and working hours – at the same time as slashing funding to hospitals and healthcare. To Australian audiences, this kind of neoliberal renovation probably sounds awfully familiar; the difference in France is that the country had already suffered from the 2008 economic crisis, and the National Front has been a steadily rising force for three decades.

Even in the home of liberty, equality and fraternity, the idea of a socialist government is a distant dream. Hollande’s Socialist Party caters to the needs and desires of the bosses and middle classes of the urban centres, while cutting ties to contemporary labour and radical movements. Hollande’s first-year term saw the emergence of a mass labour movement against the left in power, the first time this has happened since the Fifth Republic was founded in 1958. It is this distance, between the preoccupations of politicians and party functionaries, and ordinary French citizens, that helps to explain the party’s paltry vote – the worst in forty-odd years, following the SFIO’s low score in 1969 (the Socialist Party predecessor, founded in 1905).

Terra Nova Foundation – a left-wing think tank designed to advise the Socialist Party – expressed the break with the working class by suggesting that the socialist party restructure its electorate around ‘cultural values’ rather than ‘social and economic values’; basically a systematisation of the Blairite Third Way.

But as early as the first Mitterrand Government (1981–88), when the left initially won an overwhelming majority in the National Assembly, things took a turn against the hopes and ambitions of radical change. The Mitterrand Government turned to austerity early in its first term. In Le néo-liberalism à la française, Francois Denord writes: ‘From Francois Mitterrand’s electoral victory in 1981 to the commemoration of the bicentenary of the Revolution [1989], France experienced a ‘triumph of the entrepreneur’ and the decline of progressive ideas.’

The turn to austerity slowly eroded the militancy and membership (by French standards) of the trade unions. Mitterrand’s popularity fell, and for the thirty years since, French capitalism – which had held, since 1946, that, ‘All workers shall, through the intermediary of their representatives, participate in the collective determination of their conditions of work and in the management of the workplace’ – has moved closer to the neoliberal ideal, equipped with liberalised finance and privatisations. The balance of power in the workplace has tilted ever more towards the employers.

The party’s embrace of the European Union joined the discredit of the socialist left. The early austerity measures were choices made under the bludgeon of the European project. (Mitterrand abandoned his Keynesian project because it was incompatible with the European monetary system.)

Each experience of the left in government has witnessed another step forward by the National Front (FN). It started with the Dreux breakthrough and the European elections under Mitterrand. More ominously, the FN has experienced its most successful breakthroughs – from European elections, regions and the fight for the Élysée Palace – to date, after Hollande’s miserly economic measures.

Before the point of no return? The National Front

In the lead up to this election, and over the past few years, there has been too much focus on the so-called detoxification of the National Front, a notion the liberal media is enamoured with. Since Marine’s assumption of leadership in January 2011, the idea of a radically changed FN has been peddled by every respectable media source, from Le Monde, Le Figaro and BFMTV to Le Parisien. But, as the work of Alexandre Dézé – a political scientist at the University of Montpelier, and co-editor of The Swindling of the National Front: A sociology of a political party – shows, it is this very media that has created the fiction of the nouveau National Front. On the one hand, for a corporatised media driven by profits, covering the FN in such a way increases sales and market share; on the other hand (beyond the media itself) the leadership of the FN realise that the ongoing war on terror, Islamophobia, and police violence make for a favourable terrain for their discourse.

Taking fascists at their word is dangerous. Jean-Marie Le Pen understood very well that ‘politics is … before all a war of language, a war of signs, a war of models, of symbols.’ To understand the FN project necessitates going beyond these superficial appearances. The political project of the FN is to forge together a racist and authoritarian response to existing social contradictions through an aggressive form of racial segregation.

The party has so far deployed an electoral strategy towards power, and with articles 16 and 36 of the Constitution, which give the president the right to declare a state of emergency, this is dangerous. Nothing militates against their undermining the parliamentary system and democratic rights, especially in times of profound social upheaval. After the Nuit Debout and trade union struggles last year, it was representatives like Marion Marechal-Le Pen who accompanied police demonstrations to take back public space. In a recent interview with the Catholic magazine Présent, Marine Le Pen has said she’d ban demonstrations and dissolve left-wing organisations under the state of emergency. Though more fundamentally, the proposal to put ‘national priority’ into the country’s constitution is a direct attack on article one of the existing constitution that ensures – on paper – ‘the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction of origin, race or religion.’ That is, in practice – instead of building social housing and spending more on hospitals – stripping dual citizens of their French nationality and reserving welfare for the French only. This is consistent with their old slogan: ‘One million unemployed is one million immigrants too many! France and the French first!’

What the establishment commentators are not clear about and deliberately fudge is the fact that politics is a strategic art: a play of mediations, positions, relations of force, appearances and representations. The change to the foundational principle of the FN, ‘national preference’, is a good example of non-change through change: instead of saying ‘national preference’, they say ‘national priority’. This is a lexical change, not a foundational one. The turn to a Republican and secular discourse is not a major rupture in foundational terms either – it works better in stigmatising Islam and Muslims.

We must think about the FN as a strategic project aimed at winning political power. As French activist Ugo Palheta writes, ‘when one stops thinking of the political trajectory of the FN in terms of changing symbols and words, in order to think it in terms of a strategic project, Marine Le Pen’s break from her father represented no fundamental change in the party’s platform, but rather a new manifestation of the party’s longstanding strategy for gaining political support.’

It was not controversial to say that the FN was a fascist project when it was small and on the margins during the 1970s. After the 1970s, the world economic system has found it harder and harder to provide for ordinary people, which inevitably tips the balance toward rule through coercion and consent. It is in these conditions that the fascist project is fighting to make itself relevant, by renovating its discourse and appeal to broader sections of society.

Anti-establishment claims to the contrary, a fascist project in political power is a specific form of the capitalist state – an exceptional state – that corresponds to the needs of a political crisis induced by deep social turmoil.

Seen in this light, it is clear that Marine Le Pen’s assumption of leadership represented no rupture in the party’s long-term fight for power. As early as the 1970s, when Jean-Marie Le Pen was at the helm, he fought to change the party’s image (waging an ideological offensive against immigration and unemployment) to make it look rid of ultra-radical street thugs, in order to run a respectable electoral campaign. This caused a revolt among students in his ranks – grouped in Ordre nouveau – that wanted more street violence, rather than electoralism. In the 1980s, the party set up an electoral front to win support from ‘respectable circles’ and the existing parties of the right. In the 1990s Bruno Megret had the FN apparatus behind him in renovating the party’s image. Versions of detoxification are old news for French fascism. Under Marine Le Pen’s leadership, however, the party has obtained results not seen since 1972.

To assess the FN in strategic terms also means one must dispose of the term populism (indeed, the most abused term in today’s political lexicon). Populism, defined as ‘a political position that takes the side of the people against the elites’, is a term that can indiscriminately be applied to the left or the right, irrespective of national peculiarities, conditions and social content. A term as loose and fluid as this is a term that has no strategic, analytical or empirical value.

Fascism is not a phenomenon that experiences a linear development ‘organic and continuous.’ Nicos Poulantzas, in Fascism and Dictatorship, examined the tempo and pace at which fascism develops. The process is uneven, in which the periods of its growth ‘have their own pace (slow or rapid) and varying duration (long or short). The way they are grouped is itself determined by the conjunctural forms of the political crisis in question.’ Poulantzas distinguished between the ‘point of no return’ and ‘the point of no return until fascism comes to power.’ He explained the first period in the following terms:

Although the fascist phenomenon can be resisted … there is a point in its growth after which it appears difficult to turn it back. The moment is not that at which fascism actually comes to power; the accession to power seems such a simple, final act, occurring only when the essentials are already decided and done with, in short, a confirmation of a victory already won.

This moment in France cannot be measured precisely, but one must reflect on things as they stand: there is a crisis of party representation, an unstable hegemony in the ruling bloc, an elite offensive in the name of modernising France, and a significant series of working class defeats, seen in Sarkozy’s pension reforms (which increased the pension age from 60 to 62 years) and his attacks on the labour code. The vapid Emmanuel Macron, if he wins the second round, will not stem any of these tensions: he wants to sack 120 000 public sector workers and Uberise the labour market.

Based on a vicious platform of national priority – housing, jobs and healthcare to the French only – Marine Le Pen’s anti-immigrant discourse is structured around the ‘four great fears’: globalism, unemployment, Islam and Europe. This four-fold argument is designed to discredit the ‘political class’ in the name of those suffering from job losses due to automation and deindustrialisation, in ‘those in-between places where farmland gives way to retail sprawl and a sense of neglect.’ It is a means to forge ahead at moments of crisis and political decomposition.

The National Front electorate is cross class; since 1995 the popular electorate has continued to grow. It has taken from the right-wing popular electorate of De Gaulle and Chirac. From areas like the Nord-Pas-de-Calais where the party is deploying its ‘social turn’ (a term that refers to the adoption of economic policies in the FN program that are pitched to the poor) in the north-east, it is taking the historic heartlands of the left. The party is also strongly supported by a section of the voting youth, and the voting unemployed. The danger is that the FN will continue to entrench its popular electorate as the latter is further alienated from the official parties of the left and right. It wins important votes in the peripheral areas, on the outskirts of cities, certain banlieues and rural spaces where social and cultural anxieties can be tied to national identity.

The Left. Who can overcome?

Shortly after the results of the first round, the graffiti ‘Macron 2017 = Le Pen 2022’ appeared. The graffiti is a sign that the extreme centre cannot hold forever, with all the dangers this entails. But a fighting French left can provide an alternative to Macron’s inevitable attacks.

The run off between monsieur milk-and-water Macron and the fascists shouldn’t blind us to the strength of the anti-neoliberal left in the first round; a quarter of the left-wing electorate moved from the Socialist Party to Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the left-populist leader of Insubordinate France. Before the latter’s March surge in the polls, Hamon was at fourteen per cent with Mélenchon trailing behind. In just over a month, that situation was overturned with Mélenchon sweeping up the largest vote to the left of the Socialist Party in decades, and better than the far-left has done since 1981.

Natalie Artaud (Workers’ Struggle) and Phillippe Poutou (New Anticapitalist Party) were clearly outflanked by Mélenchon’s campaign, but Poutou’s performance at the all-in presidential debate burst the veil of polite society and showed what radicalism really means. He turned to Le Pen and said:

And then we’ve got Le Pen, next to me, Le Pen, dipping into the public purse … It’s not here, it’s Europe, and now for somebody who is anti-European, the worst is that the National Front, which calls itself anti-system, it doesn’t give a damn. It protects itself thanks to the laws of the system, thanks to parliamentary immunity, and so refuses to answer a police summons. When we workers are summoned by the police, we don’t have worker’s immunity. Sorry about that. There it is. Here we go.

The importance of the Mélenchon dynamic – with all the criticisms one should have of him – should be understood in the context of last year’s defeat of the struggle against the labour laws. The struggle witnessed a combative youth movement, the ‘Up All Night’ movement, demanding thoroughgoing changes to the political system, and a dynamic trade union movement. It tested the social, ideological and political balance of forces between a government intent on renovating the French economy and a labour movement intent on maintaining their conditions of work. But the social movement itself fell to defeat.

In many ways, with his left-nationalist discourse, adoration of republican secularism that excludes Muslims, and his worship of the French state, Mélenchon is as much an obstacle to a new radical left project. But he is creating a space for resistance. The problem after the next round will be rebuilding a political vehicle to harness the rage and discontent. It remains to be seen what the highly personalised Mélenchon campaign will materialise into.

If the political turbulence continues in France and the left cannot meet the needs of the moment – if it cannot sound the fire alarm and break the vicious cycle of defeats – then Macron will be preparing Le Pen’s linen.

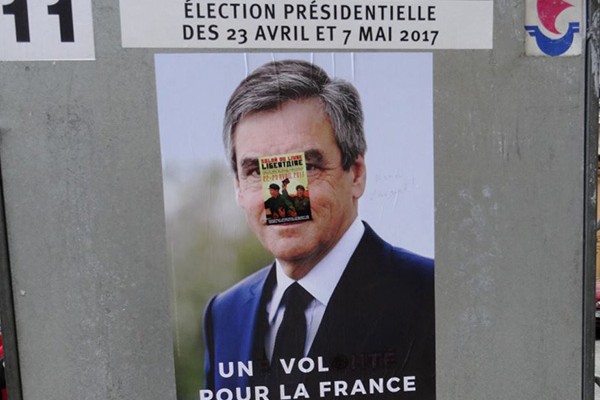

Image: Right-wing French election candidate François Fillon by Jeanne Menjoulet / flickr