Dr Tony Birch was a guest presenter at the Darwin Writers Festival in 2016 and, along with facilitating a writing workshop for the NT Writers’ Centre, he agreed to this interview before returning to Melbourne, where he is a research fellow at Victoria University. If you’re not familiar with Birch’s work, he has published a number of books, including Shadowboxing (2006), Blood (2011) and a recent book of poetry, Broken Teeth (2016). His novel Ghost River (2015) won the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Indigenous writing in 2016, and tells of a growing connection between two boys and a river, that does not solely belong to their experiences. Birch’s story takes (back) place in a setting inspired by Dight Falls in Collingwood, Victoria. The river directs themes of belonging to place beyond racial and experiential parameters.

Reading never occurs in a vacuum, separate to real life meaning-making. It was at the same time that I first read Ghost River that I read of a young Indigenous woman’s death in custody in Western Australia. The woman, Ms Dhu, had been locked up for outstanding fines and subsequently died from an infection in a Port Hedland police station. As a coroner’s report recently found, it was another death in custody that could have been prevented if Ms Dhu had been properly cared for by police and hospital staff. While imprisoned, Ms Dhu’s boyfriend was in the cell next door and could hear her moaning in agony, but no one believed his concerns that she was gravely ill.

As I read Ghost River, and the parallel narratives of Birch’s River men – their fear of police and hospitals – alongside Ms Dhu’s death and her family’s fight for justice, I tried to make sense of how to read these stories that are fictional and those that are true. And in the case of Ms Dhu, how to bear a true story that no one in positions of power cared to believe until it was too late. Ghost River is a reminder for me that things can be different if we care enough. The text proposes a model of care from the perspective of children, and for that reason, offers readers hope for a different future.

Despite some difficult questions in this interview, Birch willingly shared his own experiences that he has had with police, and remembered losing a close family friend held in custody – a darker topic he suggested not everyone is comfortable with. For good reason. Two months after Birch visited the Northern Territory, the ABC television program Four Corners released its exposé of the treatment of youth detainees in Darwin’s Don Dale Detention Centre. The majority of those tortured there were Indigenous inmates. In this interview Birch discusses the obligations of police, his role as a writer and historian, and what could be his greatest work yet.

Adelle Sefton-Rowston: It’s great to have a conversation with Tony today. I was lucky enough to meet him at a writers’ workshop back in 2006 when he was working at Melbourne University. The workshop changed the way I thought about writing and was an opportunity to see how writers think about the world. On the trip home [from that workshop] I couldn’t help but seeing people differently at bus stops and how life is made up of many little stories waiting to be written. I had the opportunity to hear you speak, Tony, on the ‘Anthropocene’ at the Literary Studies Conference in Wollongong in 2015. We’re feeling very lucky to have you up here in Darwin and I wanted to open up some questions about your novels, and your novel writing. Firstly, I’d like to start with Shadow Boxing by asking about the shift you made from writing short stories and poetry to writing your first novel, and what helped you transition to writing a longer form of storytelling. Was it the main character, Michael Birn, who insisted a story to be told as a longer narrative?

Tony Birch: Well there’s certainly a jump from writing poetry to fiction generally, although I find writing longer fiction there are what I call poetic imagery that is very strong and there are moments where I need to write a note or a couple of lines of a poem to give [make more visual] that place in the novel or longer text.

Shadow Boxing was published in 2006 and is what you’d call a hybrid-text and although some people call it a novel, others call it a collection of short stories, essentially I was really informed by a collection of short stories called Drown by an American Novelist Junot Diaz, and I was fascinated by the structure of this text that followed a central character through a series of stories about growing up in the Dominican republic and then moving as immigrants into public housing in New Jersey in the States. When I read the book it felt like a good model I could emulate and I made a very self-conscious decision to literally write a list of very dominant memories of my own stories that were seminal to my central understanding of how the world works. In a way you can see them as repeated stories that were told often around the kitchen table. They’re strong memories I see as parables for life in the sense that all of the stories in that collection can be read as a distinct entity and that was quite purposeful so that if anyone picked up those stories individually they could read them as a self-contained short story and in fact, several of them were published separately before the novel – I had to rejig them a little bit so that as a whole they would read coherently like a novel. So structurally that was the issue, the other point you raise of course is having a central character or a protagonist in Michael Birn whose voice became a first person narrative to create a sense of evenness and logic to the text so that because we are following Michael through from childhood to almost middle age we [readers] are provided with clear links and maps, if you wanted to read it from cover to cover.

ASR: Was that difficult taking personal stories from your life and transform them into a novel?

TB: No. One of the first observations I made when going to the University of Melbourne as a thirty year old was that people could eat at the table with a knife and fork and their elbows off the table, which I still can’t manage to do, because the middle class practice that from birth, so, I learned about what people might consider narratives of privacy but where I grew up there were no private stories. You told stories, or people told stories about you, again around the table and these were signatory stories or biographical stories so that you or any of your students were to come into my house, someone would tell a story about me or I might tell a story about another family member which welcomes and introduces that person to the house. And because I lived in a very poor area of Fitzroy in the sixties and seventies – for Aboriginal people, poor white people and migrants – privacy was a privilege that only a few had because we lived in very crowded spaces or social workers and police in those days felt they had a right to involve themselves in your life so most of our stories were public anyway, so I wasn’t concerned about that until I started to reflect on the impact those stories might be read today about family members, so I did take it very seriously but I didn’t feel I was revealing private information. There’s nothing in that book, even when dealing with domestic violence or murder that wasn’t public knowledge so my family read the book as pretty much biographical or autobiographical fiction. There’s nothing in the book they felt uneasy about except that my mother thinks that she’s a better story teller than me and she would have got much closer to truth. Interestingly the mother in the novel is a woman who suffers greatly at the hands of her husband in regards to domestic violence and my mother would never shy away from talking about that as an issue nor would any of her female friends of that generation. It is quite interesting that we have a national discussion of domestic violence now which is absolutely vital but it’s a topic that hasn’t been spoken about and I understand that but where I grew up, people always spoke about abuse amongst other women. They may not speak to the police about it or they may not speak in the public environment about it but when you’re a kid and you’re sitting around with your mum, your grandmother and their mate, they would talk quite vividly about their husbands and it was unusual as a kid I suppose to grow up hearing their mother talk half-jokingly about killing their husbands and you think, well they wouldn’t really but, one of the things I’ve always noticed when going to family and community funerals was to be honest, for the older generations, the death of a husband comes sadness, whether we understand it or not, because they still love these men but also a great sense of relief after being free of men who treated them so badly.

ASR: And so you mentioned this tension with police and not being able to report these stories of domestic violence and this comes through your novels Blood and Ghost River. In particular Blood opens with a policeman coming into a ‘room carrying a tray of food. Two cheese burgers, some fries and a Coke. She put the tray on the wooden table. The top was scratched with initials and messages – FUK THE COPS.’ Similarly, your recent novel Ghost River is etched with messages about police and their poor treatment of Indigenous people in particular. Page 53 for example in Ghost River reads ‘Get yourself lost on the street late one night and see if you can make it home without police tracking you for a belt… Before you come here there was a robbery at the TAB… the next day the police pulled this kid off the street for it. He wasn’t much older than you and me. They took him to the cells and bashed him and the kid died… Other police who come to the court to watch the case laughed when it was over, in front of the boy’s mother. So don’t tell me this is a free country.’ For me this is a stark reminder of the far too many deaths in custody and general treatment of Indigenous people in our larger society. How do your novels address the urgent issue of better treatment for Indigenous people who are incarcerated?

TB: Well obviously Ghost River is a historical narrative set around 1970 whereas Blood is set in more recent times. I think it’s important to give people a sense of that period I’m talking about in Ghost River and that it’s based on a real life case of a man called Neil Collingburn who was a very close family friend of ours and died in the Collingwood police cells. There was a trial and in that trial, anyone who has read anything about Aboriginal deaths in custody would know he had horrific injuries on his body, there was no doubt about that, that evidence was given in court, there was no doubt that the brutality that he died from could only have occurred outside the police cells. Yet the policemen who stood trial for that murder were found not guilty and regardless of the recommendations of the original Deaths in Custody Report or what has happened since, it is very rare for these matters to come to court as criminal action and as we know with the terrible Palm Island incident of recent years that when cases did come to court it would be even more rare for a policeman or anyone in a place of authority to be held responsible for those deaths and face a prison term. So my point is there is a complete disempowerment of Aboriginal people and looking at my work in the inner city, this doesn’t exclude any poor people, whatever your background and I know the same has happened with migrants who came here in the fifties and sixties and suffered various levels of abuse but what Ren articulates to Sony in the quote that you just read is that what he understands, he states it as a fact, not as something he is outraged about. He just wants to remind Sony of how the world works, so part of my fiction writing is both to convey a sense of that level of violence, but not in a way that suggests there can be much [that] can be done about it. That’s not in a sense of helplessness but that’s a sense of being pragmatic and realistic about situations. The other thing that’s relative here is in relation to domestic violence against women which comes out in Shadow Boxing and particularly in the story ‘The Butcher’s Wife’.

I am also a historian and did my PhD in urban history and I interviewed many people about police in the inner city after the Second World War and I interviewed a woman whose brother had been murdered – shot dead – in Fitzroy in the early sixties, not by police but when they did a post-mortem on him, an autopsy, they found he had severe cuts and bruises all over his body which were about two weeks old and the investigating detective who came around to interview the woman asked if she thought the man who shot him could have been involved in an altercation with him earlier. She said, no that happened in Fitzroy Police Station. Now she told me that story which is relative to the second story – she talked also about the violence she had suffered at the hands of men and although I knew the answer, I said, why didn’t you go to the police? And she said why would I go to one man who acts with such violence to tell him about the violence of another man? So basically she regarded men she had relationships with and the police as having very similar attitudes and had no trust or faith in either of them. It put women in a very difficult position and instances where their only means of escape was to kill those men, which they did, on occasion.

ASR: Just to shift focus back slightly to Ghost River –

TB: Something a bit lighter [laughs].

ASR: Sorry this is getting a little heavier, but I’m reading Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor which is a nonfiction account of myths around cancer and tuberculosis which she wrote while fighting cancer herself, and in her work she rights of two types of citizenship, those who belong to bodies which are healthy and well and those who live in the kingdom of the sick. What I’ve [read] in this conceptualisation is that there is no in-between and there is not a discourse on the racial manifestations of those who are Indigenous or treated as second class citizens yet coupled with being critically ill. For me, Ghost River points to the complexities of fighting for sovereignty while also residing in the kingdom of alcoholism, homelessness, death and disease but it is also about hope. For example on page 175 of Ghost River we read how, ‘He [Ren] understood for the first time that while the river men enjoyed an adventure, their lives could also be miserable, with no warm bed to sleep in on cold nights, no family to take care of them, and the grog killing their bodies. He opened his window, looked up at the clear night sky and remembered reading in a science book that some of the stars, glowing millions of miles away, had been dead a long time.’ For me, the river is pathos, speaking of how incredibly unwell our body-politic has become and our nation’s poor state of race relations is. Yet, it is your sublime writing of the River which points to the possibilities for healing and, for Indigenous people to realise a particular citizenship, despite colonisation which is intrinsic to ancient culture and place. Are there elements of hope that enlighten your work when writing about such serious and saddening content matter?

TB: Well I always think so [laughs]. Even in reviews by people who like my work, describe it as bleak. I understand that at a superficial level but I never intentionally write bleak books or intentional stories of misery and, I am being quite honest about that. The stories that I write, reflect for me reflect a reality, not in the sense of a nonfiction reality, but the reality of emotion I am trying to convey and in regards to the river men, this story from my perspective is not one of hopelessness. It might seem like a contradiction but the reality here is such that when I was a boy there were many more homeless men living around the inner city down by the River and up back lanes. Now Melbourne’s population is greater but we’ve pushed a lot of homeless and marginalised people out of the city and we now see homelessness as a ‘hidden’ problem quote unquote. When I was a boy you would see, not as many homeless women or kids then but certainly a lot of homeless men and the point was that from going to the river, we knew these men by name, we were not afraid of these men and we felt these men had a more free and adventurous life than us that we wanted.

The quote that you read out reflects what happened to Ren and what happened to me, and I did want to convey this to the reader, these men on occasion drink methylated spirits and methylated spirits will kill you very quickly, it does terrible things to your body and I’m sure there are still parts of Australia now where it’s still used and I wanted to strip that image of the boys from a romantic sense of reality to show them how by the end these men become quite decrepit and are wasting away. But having said that, the central character in the book Tex, or the central character amongst the river men, is an Aboriginal man who has obviously fallen on hard times but he does have a really strong central relationship to the River and the Aboriginal narrative of formation underpins the River, and I wanted to give him that role of authority but in a way that he could speak about it in the vernacular of the time and in a vernacular of what you might expect a homeless man to say, so I didn’t want to articulate a post-twentieth century narrative of Indigenous essentialism that we sometimes get trapped in these days. So I would hope that people who read the book have a great affinity with Tex as the boys do and have a love for him, and have respect for him but also understand the great sadness of his experiences because Tex epitomises the story of a lot of Aboriginal people of that generation – he ends up on the street because of a peculiar act of legal discrimination and again this is loosely based on the fact that Aboriginal people regardless of the level of the position they may have held in Victoria at the time, the liquor laws were such that an Aboriginal person could find themselves in gaol for something as meaningless as buying a couple of bottles of beer and taking them onto a mission or reserve, which happens that we find Indigenous people being incarcerated for what we would regard as menial acts but [as a result] of racial discrimination could get that person into a lot of trouble. Consequently, with a character like Tex it really impacted negatively on his self-esteem and sense of dignity. So not as many now but when I was a kid those Aboriginal people who were great mates of my old man and would all hang out together, I think you saw in those people sometimes a sense of shame that they were carrying the weight of racism when it really should have been the responsibility of white society. So you find at a superficial level, a lot of beaten down people who have had their kids taken in some instances, they’ve been pushed to the margins of society and there’s not much left for them, except their comrades. The other thing that’s relative to that is a general level of poor health among Aboriginal people because of that history of discrimination. I’ve had a lot to do with the Aboriginal health services in Melbourne. My sister is an Aboriginal health worker and prior to the Aboriginal health services being established, as we know from issues like Aboriginal deaths in custody, and I’m sure that people in this part of Australia [Darwin] would now this better than I would, Aboriginal people literally being turned away from hospitals, suffering from respiratory illnesses and sometimes suffering from heart disease on the basis of a discriminatory viewpoint from a hospital staff member that that person is drunk. So we know that in the deaths in custody royal commission, many Aboriginal people who presented at hospitals with what would otherwise be seen as respiratory or general health issues were turned away because their state was misdiagnosed, and when I say misdiagnosed I mean if they were even given a diagnosis, and have been accused of being in a drunken state, and of course they weren’t. And even if they were in a drunken state they still needed to be taken care of but in many instances, people hadn’t been drinking at all.

ASR: The most recent example that comes to mind is when Gurrumul Yunupingu ended up in hospital and was racially profiled as having symptoms related to drinking.

TB: Yeah and that story received a lot of coverage in Victoria. There was also a terrible case last year of a young Aboriginal woman dying in custody in Western Australia and they’re really important issues to me. We discussed these at a forum in Melbourne at the same time as the booing of Adam Goodes became a national issue. A lot of us felt it was terrible to boo Adam Goodes – he’s a great sportsperson and an articulate Aboriginal man. It was interesting that the next AFL game he played at Sydney Cricket Ground he was given, more or less, a standing ovation which was fantastic. The same woman that died the same week he was booed there was little coverage of that in Victoria and no one stood up for her; it wasn’t a dominant conversation on Q&A the next week and one of the things I feel is that the issues of discrimination that are given some priority in Australia, like the Goodes case are dealt with really at a superficial level while fundamental issues are not addressed at all. As much as I think what happened to him was wrong, there’s nothing easier than standing up at the SCG and clapping Adam Goodes as opposed to making real changes in regard to what’s happening to nameless Aboriginal people who don’t have any status in the media and that’s where the real ongoing damage is being done.

ASR: I remember finding that article about the Western Australian woman who died in a cell at the same time I was reading Ghost River so it was another layer of emotion for me to read the fictional story but then the real story of how this young woman was weeping from her cell some time before her death and that she wasn’t given medical attention and raises larger questions about how we treat Aboriginal people who are sick, and in this case dying.

TB: And again, the issue in Ghost River of those men knowing that their only place of sanctuary was on the river and when they’re on the street they can suffer brutality at the hands of people, including police, but that’s complex as well because it is true that, I know you don’t have them in Darwin but, winters used to be very cold in Melbourne, not so much now with climate change being a problem, but I know men who would literally smash the front windows of shops and wait for the police to come and if they didn’t get locked up they’d go and smash a window again because they liked to spend the winter in Pentridge where they’d sometimes have more chance of survival than they would on the street.

There is also the complexity about institutional power and individual behaviour of police. I wrote an essay about Thomas Hickey, the Aboriginal boy who died in Redfern during the so-called riot and I found some of the media coverage of that really horrific in regard to the demonisation of young Aboriginal people but also even in the critique of that, I still find the most saddened and poignant outcome of that is that he actually died in the arms of a policeman and they interviewed that policeman and the way that policeman spoke indicated something very different than you might expect in the sense that at an individual humanistic level, that policeman felt great sadness for what had happened but once you put that into an institutional context that narrative has no place, so it was never mentioned again. And I believe to this day that the comments he made were truthful and there was no suggestion that he had acted untoward Thomas Hickey but it’s one of those things that state power and the way that we act when we’re inside institutions often strips us of our own humanity or that potential. We see this with politicians all the time, before they go into parliament they seem like reasonable people and then when they have to go into parliament and tow the party line on say he treatment of asylum seekers and refuges we see people coming up with the most banal but the most horrific statements. I’m really interested in the way that institutions function to disempower people but also to strip people within those institutions of their capacity to engage with others in the more humane way.

ASR: If we could just digress a little bit, another great essay you wrote was on the film Beneath Clouds where you suggested the road acts as a textual motif; do you also see the river in Ghost River as a guiding line for the plot’s structure or when you were writing the novel did you see the river as more a protagonist in the text?

TB: It’s interesting, because the Yarra River in which Ghost River is based, has a very particular history which drove the motivation for the novel from the outset. The scientific, in Aboriginal reality around the Yarra River is that it’s a very young river – it’s about 10 000 years old and prior to the formation of the Yarra during the end of the ice age there was no place called Port Phillip Bay, the Yarra River or the mouth of the Burung River – the Aboriginal River as it was then – the mouth of the river was at Port Phillip Heads, it was just a much narrower opening into the ocean. I can’t go into this story, it’d be too long to tell but before the so called collapse of the land bridge between what we know as Victoria and Tasmania – the Burung River hooked up with Canar River which was the one river and came out the bottom of Tasmania, so its history is remarkable. The point for us is that, that story of the formation of the bay is a geographic narrative told by Wurundjeri men and women to first arrivals and occupiers from Europe and a guy called Jesic Tysjellabrak in 1835 was told that story of the formation of the Yarra and the formation of the bay by Wurundjeri and he wrote it up and documented it but he dismissed it as folklore and myth. You see books where you know Aboriginal folklore and myth are about superstition and creation stories but what the Wurundjeri were telling Delegram were scientific and geological stories. It wasn’t until 2005 that two archaeological divers were sent down to Port Phillip Heads where they knew there was a crevice at the bottom of the shipping lane which is very shallow, fourteen metres deep, and people from Victoria will know that the State Government had a remarkable idea to dynamite the bay down to seventeen metres so they could bring super tankers in so when they have an oil disaster so you have a huge tanker, so why stop at something smaller [laughs]. When the divers went down, they kept going and going and eventually these two divers stood on the bed of the original Burung River which is 102 metres down. People might think, well how is that possible that the sea rises 102 metres and not flood the rest of the continent but because I work on climate change I’ve done a lot more research in this area and believe it or not, I’m not a scientist but the ice age is not simply a matter of ice melting and seas rising – it’s the rising and collapsing of land formations – the physics of the end of the ice age shows incredible shifts in tectonic plates, so we literally had the collapse of some land and sea rising but basically part of the Ghost River Story is because Tex knows that story as a reality and one of the things I’ve been working on in my new job is to look at Indigenous stories across Australia about weather and climate and country, to find if those stories hold really valuable historic and scientific information which is of grave assistance to us understanding the current phenomenon of climate change.

To go around it the long way, in relation to Beneath Clouds I think what is so poignant about that film is that if I could say there is a relationship between the Burung River or the river in my novel, is home. The men don’t have to go anywhere; they’re grounded in place. What’s so poignant about Beneath Clouds is that for Vaughn, the male in the film, he escapes from the prison farm and he is going home. He is using that road to get back to his mother, and even though when he finally gets there he discovers a shocking sight when he opens the door, whereas Lina is running away from home and in a sense has nowhere to go or she doesn’t know where she is going. She is literally running from her domestic home and Vaughn is going back home. In the space of that journey, I would say they’re growing love for each other and there is that wonderful scene at the end where she gets on the train and gives him a hug and there’s a tear in his eye. Home for me, in that film, is in each other – so in family and community. I’ve often said this, but people need to understand that in historic terms when this country was invaded by Europeans and certainly Europeans South Eastern Australia in the eighteenth, nineteenth centuries were stealing land and killing people as a method before the missions and reserves systems, is that when that failed, failed to destroy the fabric of Aboriginal society, Victoria where I come from was the first colony at that time to institute the half-caste Act so what people around Australia understand as caste legislation, discriminated against Aboriginal families by separating families, and was the foundation stone of the stolen generations policy – this was initiated in Victoria in 1886 [and] called the Aborigines Act and it literally attempted through legislation to legally separate Aboriginal people into categories of blood and soon saw family structures disintegrated. If people ask what is most important about retaining your sense of Aboriginal identity or what is it that non Aboriginal people find most confronting, I don’t think it is black, I think it’s family and genealogy or what Europeans call relationships with totemic systems etcetera. I’m not ashamed at all to say that in Victoria where historic communities were formed out of a great sense of loss, many of those traditions were taken and lost, but the two institutions in Victoria – the Framlingham Aboriginal reserve over in the West and Lake Tyres in the East were established as sites of incarceration of Aboriginal people and, I should note that when people talked about Lake Tyres in the first world war they talked about the final solution of extermination and eradication of identity. Those two reserves have some of the strongest Aboriginal community members in Australian and they thrived because of the inability of that institution to destroy family. So I think that for Aboriginal people to survive, you could lose everything but if you have each other, and this is the Walt Disney ending, if you have each other you still have the ability to survive all the forces of colonisation that have been thrown at you.

ASR: Blood has been described as a ‘compelling, gothic odyssey that explores landscape, place and the “ties that bind”.’ What is your understanding of the Australian gothic as an Indigenous writer and how have you informed this genre do you think?

TB: I love that quote because it even throws in a Bruce Springsteen quote at the end and my work’s more influenced by Springsteen than it is by the Australian gothic [laughs]. I would say overtly that both Blood and Ghost River are not genre novels and not quite crime fiction but in some ways they are influenced by the crime genre. I would say that I am much more influenced by modernist American gothic. One of the most important writers for me is Flannery O’Connor who is one of my heroes, her story A Good Man is Hard to Find I used to teach this in creative writing at Melbourne University and students would just freak out about this crazy misfit, where students are shocked because he kills everyone, her whole family with no real sense of menace, you know it’s just got to be done [laughs] and students freak but I like this story because the author brings together the understanding of the physical environment and its impact on people, as a Southern writer and the darkness of Christianity and she was a highly moralistic Catholic woman and for a long time housebound because she suffered a lot of illness, so she was able to capture the trajectory of human society which is about a darkness that other writers don’t capture. In regards to the Australian gothic, I’m not ambivalent about [it] but I have a particular view that it can collapse into cliché. I often go to conferences where non-Aboriginal people will say things like, and if you’ve written this in a paper I apologise in advance: ‘It’s not the sound of the Australian landscape that is so eerie, it is the silence’, and then the audience goes, ‘ahhh’ [laughs]. Now that’s just bullshit and when people talk about a haunting landscape, and this might be sacrilegious but I don’t give much credit to that. I taught a student once when I was doing a lot of writing about the Western District and there was a lot of physical abuse and murder and students would tell me that when they drove out they were haunted by the deaths of those children, they could sense them around me. I find that is a co-option of violence in a way that at the same time gets that person off the hook of responsibility because it gives it a supernatural quality. Whereas, when you read about those acts of violence there’s nothing supernatural about them, they are homicidal, but they’re systematic because there were people who killed them, so they’re all totalitarian regimes with brutal efficiency. I talked about this in relation to The Secret River by Kate Grenville which I think has real qualities but one of the characters in that is a psychopathic menace who in the novel and play, drags this settler convict into this behaviour of violence and it locates European violence against Aboriginal people in that pathological environment. When I think in terms of Australia, I don’t mind if it’s melodramatic as genre fiction but when it tries to play on this sense of the haunting in the Australian landscape, haunted by the deaths of Aboriginal people, I find it really uninteresting, to the point where I don’t even want to write about it because it annoys me. In my books I talk a lot about landscapes and in Blood in particular when those kids are moving from South Australia to Victoria across a very barren landscape, where death pervades the landscape during periods of drought. I believe that country is not interested in this, country is not interested in some white person’s melancholia or their sense of being haunted. I love to quote a friend of mine who is an Aboriginal activist Robbie Thorpe and when he speaks about land rights he says ‘what we’re talking about is the right of land not our rights to land’ so in that sense land has inherent rights and an inherent sense of dignity that doesn’t require those superficial narratives to give it meaning.

ASR: That’s a really important point and this is an area that obviously needs developing and an area you could contribute to.

Tony: Although I don’t know that I will [laughs]. Seven Versions of an Australian Badland and Ross is one of those great maverick thinkers in Australia but even that book, I can’t quite accept it, that the land creates menace. I think that menace is something that belongs in human society and why I think it’s important to note that is because we – as a collective global community – we treat land and country in such a degrading way that, that’s where we need to focus our relationship with place and landscape is our inability to give place that respect and dignity and not create some sort of hokey-pokey story about it. I don’t know if that’s a literary term, hokey-pokey [laughs].

ASR: We can quote you and make it one. But what you’re saying rings true in Ghost River when we see Sony and Ren’s initial fear of the river, because of the way people are creating menace about the river. We see the river as scary because gang members are dumping bodies and old motors yet by the end the river becomes a place which is like their home.

TB: Essentially my day job is to work on climate change and part of my work is to work with fifteen year old kids from all around the world on a project on climate change and creative response and I visit schools in Dublin and London, Berlin, Poland and I work with kids in Melbourne and rather than consider place or country as something which can do wrong to us, I talk about the fact that if you love a place it’s okay to say it; it mightn’t sound cool to talk to your mates on the way home from school about your love for place but if you love a place, talk about it, write about it and through that you come to want to protect it more and want to engage with it more. For me, part of writing Ghost River was to write a love story – Ren and Sony, they love the River. They come to love it and, when there is a threat to it by the construction of the freeway that is going to take a lot of their important places, they are very angry and they want to do something about it. When I was a fourteen year old boy they built the Eastern Freeway in Melbourne and blew up our swimming hole, it was just horrific to see that. And people might think, well it’s just a few kids hanging around the River but it’s not. It’s desecration and it has a knock on effect. I now think that when people drive along that freeway and are oblivious to what happened underneath it, and they see it as a conduit between the city and the suburbs, I question what respect they have for the places that they live. They think of nature as pristine places somewhere ‘out there’ but we have to consider what kids think about their backyards, corner paddocks in Dublin, the streets of Berlin, so nature or country is something we think about as part of the cities and not something ‘out there’.

ASR: Yes, all places of home should be cherished and respected. Well we’re almost out of time but if I could just ask one more question? You’ve been quoted as having a mantra: ‘You’ll be great, but only if you work your arse off’. What’s the next big thing for Tony Birch and how will you continue to work your arse off?

TB: Yeah I will. That was a quote from a teacher when I did night school as an adult doing my HSC in 1997. That was a comment made to me by my teacher Anne Mitchell who I still know. I’ve found in the last twenty five years that anything I’ve maintained a focus in I have to write about it. I find the need to write about it. That’s probably why I work in different genres. I don’t write as much poetry now, even though I’ve just had this new poetry book come out [Broken Teeth] most of those poems are years old. I’m writing a novel at the moment and because the climate change project I’m working on at the moment has another four years to run, I’m probably of the view that in the medium term, and possibly the long term, I think my writing will shift more to focusing on the issue of climate change. But it may in fact be something that takes me out of academia as well so when I think about what I want to do post-University life it would be to work more directly in this area so literally working with organisations at the cold face of climate change discussion. I’m a great believer of direct action and I’ve found in recent months that there’s a need to become re-engaged with political action as a climate change activist. I’ve been invigorated by the number of young people I’ve met who have at times put their body on the line and I’ll probably end up getting my arse whipped by the coppers [laughs] but I think that’s what I’ll be doing. I have a four month old granddaughter and I know it can be a cliché, but I’ve actually thought consciously about what sort of climate will there be in fifty years for her and I know it’s going to be different so I don’t want her to think her grandfather or her parents didn’t try to do something to make change. I’d hate to think when she’s a twenty one year old woman that she thinks well he might have worked his arse off writing fiction but he did fuck all for the planet. So I want it to be the other way round.

ASR: Hmmm.

TB: I swore [laughs], Sandra [Thibodeaux] said I could swear.

ASR: Thank you for such an intelligent and insightful conversation about your books, science, history, climate change – we really appreciate it.

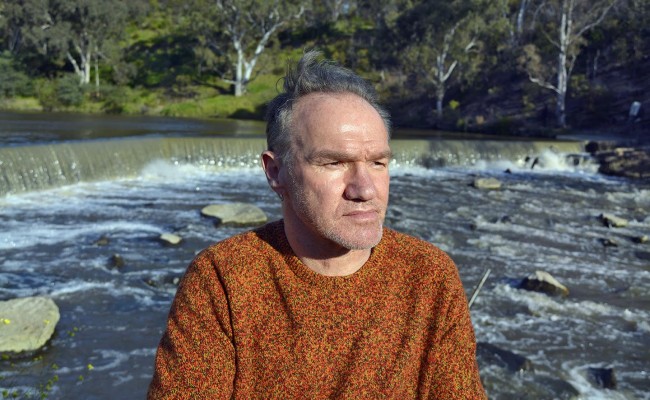

Images: Tony Birch by Michael Rayner courtesy The Weekly Review