It has been instructive to observe the different kinds of desperation with which different kinds of commentators on the political spectrum have weighed in on the aftermath of the US presidential election. I want to hone in on only one here: the unsurprising but egregiously misguided grappling tactics with which Slavoj Žižek, as perhaps the major public representative of a European philosophical mainstream, (that is also a loudly-advertised subversion of it) has tried to maintain some grip on philosophical credibility in the face of unprecedented threats to the very intellectual constituency that he inhabits.

His stance has been signalled at various points before, during, and after the election, at significant nodes of the big-player network. Wikileaks, above all, was quick to post to Facebook, on November 4, a Channel 4 News video from the day before of Žižek endorsing Trump as his candidate of choice. Published on November 15, a Russia Today interview with Žižek has him repeating, somewhat chastened in the rainy streets of a post-election Manhattan, the same mantra: that Trump is unconscionable but preferable to a Clinton Presidency.

What do Žižek’s claims amount to, now that that possibility is fact? What might before the election have passed, ironically, for an aspirational rhetoric, a hope for a radical displacement of what Žižek calls ‘status quo’ Democratic exceptionalism and the kind of impunity Clinton Inc. appeared to sustain almost to the end, (despite, above all, Wikileaks’ efforts to derail it) now promises something more radical than even Žižek had in mind. The gist of his pre-election ‘desperate, very desperate’ hope in preferring a Trump presidency was that it would necessarily entail a total recalibration of US bipartisan political consensus, in which both parties would ‘have to return to basics, rethink themselves’ in a ‘kind of big awakening’, through which ‘new political processes will be set in motion’. He acknowledges the danger, especially, of the legal implications of Trump’s proposed rejigging of the US Supreme Court, among other policy bugbears of his election campaign. Clinton, on the other hand, stood for an ‘absolute inertia … the most dangerous one … pretending to be socially progressive’.

Žižek pivots these more or less anodyne characterisations against the other, and surely he is correct that the ‘establishment elite’ will require an intense period of self-scrutiny, that Democrats and Republicans alike will be reeling in a worse electoral shock than any so far this century, that the political process as Western liberal democracy has known it has suffered the worst disabusing of its putative moral authority since, quite possibly, January 1933. Nevertheless, Žižek is willing to allow that this is preferable to a Janus-faced liar and agent of corruption, what Assange called in his November 5 interview with John Pilger the ‘centralizing cog’ in ‘a whole network … of relationships … with particular states’. For Assange, these include(d) ‘the big banks, like Goldman Sachs and major elements of Wall Street, and intelligence, and people in the State Department, and the Saudis, and so on’. No great surprises here, and Wikileaks was untiring in demonstrating evidence of the same claims. They also fit neatly with Žižek’s catalogue of ‘status quo consensus’ that he wants to see Trump dismantle, come hell or high water.

Even where Assange has the grounds to be right, and Žižek can be justified in taking that cue to mobilise it in a critique of hegemonic Clintonian hypocrisy, (what he and Assange condemn as her self-interested willingness to recruit both Saudi oil-money and LGBT rights to her democratic cause) it is also the case that Žižek misplays the ideological advantage his case might make for him, and many of the rest of us ‘ordinary people’ who are concerned to consolidate his and Assange’s critique of the exhaustion and bankruptcy of Democratic self-representation – the thing that, for most, is what cost Clinton her coveted post.

The self-description ‘ordinary people’ is intended because it is in its notoriously vague and even untenable reference that Žižek makes one of his apparently inoffensive mistakes. The first was to assume that in some equally vague capacity Trump and his not-at-all-ordinary billionaire’s club is in any sense not an integral, if antagonistic, part of the Clinton-friendly network of the ‘Wall Street status quo’. His second is to imagine that the ‘ordinary people’ who gave Trump their vote – as would have Žižek himself – are either ordinary, (or qua ordinary) or wanted to elect an authentically ordinary candidate (any ideas?) to the White House. Because Žižek also claims that like those who wanted to see Sanders win, they are ‘anti-establishment people’. Neither Žižek, Trump’s voters, nor Trump are in any sense ordinary, whatever that might actually as opposed to expediently mean.

Rather, Žižek, the ‘ordinary people’ and Trump himself have proved hyperbolic in the truest sense, and as equally prone to flagrant over-statement, inaccuracy and blindsightedness of the most intellectually irresponsible kind. No one needs to reiterate the extraordinary embarrassment that was Trump’s effort to engage in anything like intelligent and coherent discourse with the Democratic nominee and his own domestic critics. All too many of the ordinary Trump-folk of America were seen in multiple media to betray a basic ignorance of or indifference to the sheer seriousness of the moment of the world, well beyond domestic US conditions, that in itself should have long-before disqualified Trump from his candidacy. Mike Pence denies the scientific evidence for evolution and climate change, a fact which will make it all too easy for Trump to sideline himself in opting out of US commitments to the Paris Accord. We won’t begin to speak of likely Republican healthcare, gun-ownership, civil rights and foreign policy, because it is already far too depressing to contemplate.

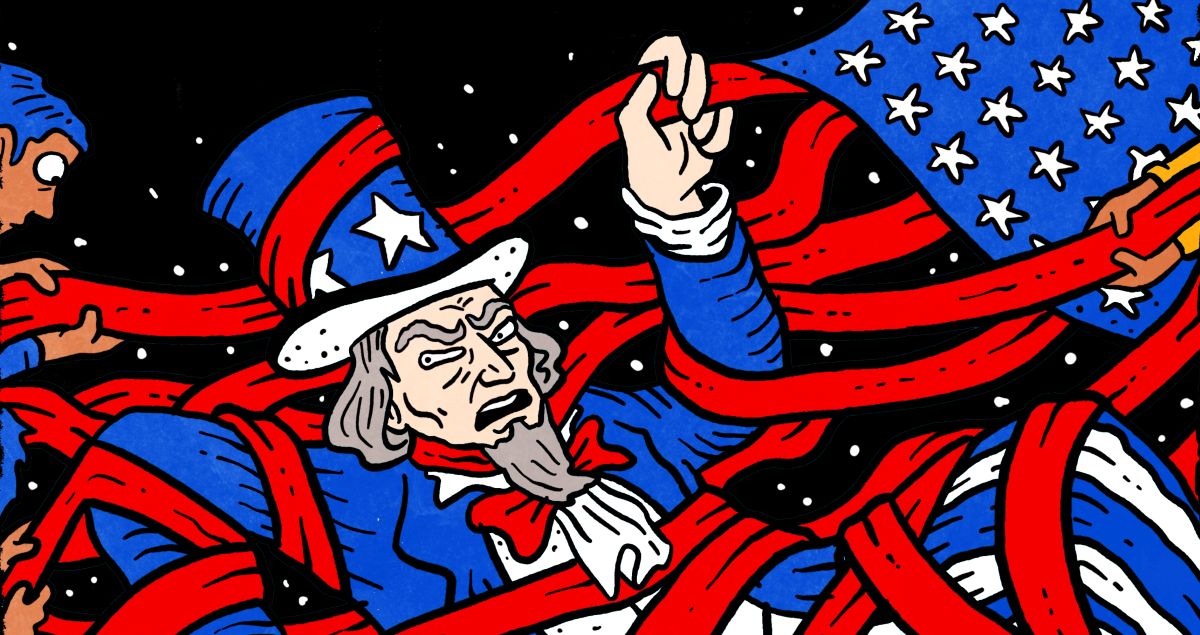

Nor has there been any surprise in the spike of race-related hate-crime in the streets of America, and throughout the web since November 10, a fact that Trump’s incoming chief strategist and Senior Councillor Steve Bannon will all too obviously relish even if Trump himself is careful to be seen not to. These people, and the media agglomerations that support their frequently litigious claims, are not ‘alt-right’, whatever that aseptic and transparently white-washing euphemism is actually meant to signify (pun intended). They are agents of white, male, monied privilege and supremacy, pure and simple. They are agents of hate-speech, hate-acts and self-serving mendacity that, especially but not only in their most frank neo-Nazi guise, would in most Western putative democracies be unable to reach the back pages of the shoddiest tabloid rag let alone the hallowed corridors of the most powerful democracy in the world. We have entered a moment of a fantastic travesty and reversal of decades’ of global evolution out from the shadow of precisely the conditions that sullied so much of that century, and threaten to irremediably ruin this one.

And Žižek wants to call its praises, however qualified they may be? How could a major intellectual get it so wrong, even and especially when he sounds almost right? On November 15 he suggested that ‘the traditional machine [for] manufacturing consent no longer works’. He may well be right in this, unless he is referring to the same machine that, with some minor adjustments, will now seamlessly be able to manufacture a new shape of consent for a far more dangerous driver than Clinton Inc. might have been.

But can Žižek really intend this as the preferable state of affairs? Trump’s embarrassments and indiscretions ‘even helped him because ordinary people didn’t identify with an ideal Trump. They perceived him as one of us precisely through his vulgarity, mistakes and so on. That’s how political identification works’. Again, the profundity is mind-boggling. Žižek even chuckles at his own suggestion that ‘ten years from now, and it’s not a joke, rape will be called “enhanced seduction technique”.’ It’s good to know that he’s not joking, in case we thought he might have been taking rhetorical liberties: Žižek means to say that he means what he says.

Donald Trump is, for Žižek, a ‘basic ethical catastrophe’. We suppose Žižek means this in a way he doesn’t mean the other things he says he means. Many would agree with him. And Žižek helps them, and us, wipe their hands of any incentive to assume that that is as bad a thing as it really is. He says we ‘should not focus on Trump as a person’. Perhaps we should focus on ‘the new face of power’ as a cipher that legitimately represents any number of variables as possible, instead. Perhaps the philosophical margin-caller has always been as naïve, and as futile. Let us hope that Žižek has reason to hope, as he claims he does, even when that means betraying his own, and our, reason. As he says, ‘Again, the situation is open’. For how long will it remain so?