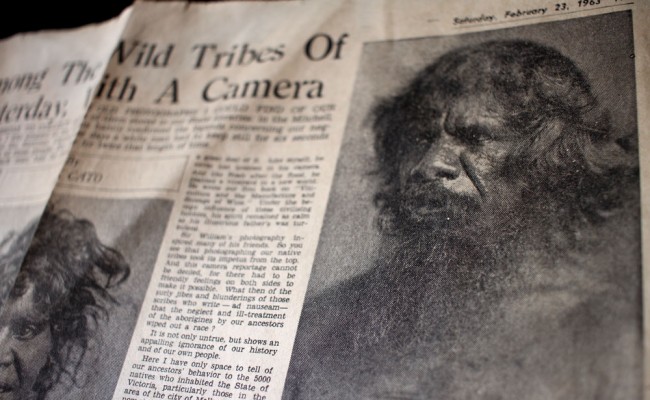

We found it under the carpet, ripped up with the old insulation and the dead spiders and the underlay – a lost page from the Age newspaper. It was faded yellow now, dated Saturday 23 February, 1963. Page 17.

On one side was a story about the rise of a Melbourne publishing giant. On the other was the paper’s ‘literary supplement’ – four historical photographs of Indigenous Australians and the headline: ‘Among the wild tribes of yesterday, with a camera.’

One photograph of a man with shining dark eyes and a thick beard was captioned, ‘A splendid portrait of one of our aborigines in the brush and comb period’.

The picture beside him was of a young woman. This time the caption invited readers to ‘note the wild, matted hair’ of her ‘natural state’.

‘In the old days,’ it goes on, ‘a white man had to keep still for six seconds before the lens; a black man had to hold for twice that length of time.’

The page had been in the house longer than we had. It had been read, folded, spilled on, spread out across the creaking old kitchen table and then flung down as underlay for the new carpet.

That we found it, just three days after The Australian published a Bill Leak cartoon characterising Indigenous fathers as neglectful alcoholics, gave an odd texture to the page. I reread the date. 1963.

When I first found the paper, it seemed far-removed, like something glimpsed through museum glass; a forgotten relic from a time when people used the word ‘savage’ while they smiled and drank tea. But the more I read, the less strange it seemed – just how much has really changed in fifty years?

In a nation of more than 23 million people, today only around three per cent of Australians are of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander heritage. That means that for many people, Indigenous Australia is a media product, rendered through television segments and newspaper columns on, for example, remote communities, domestic violence, ‘closing the gap’, and debates on land rights and constitutional recognition.

This distance puts a very potent kind of power in the hands of media outlets who have the power to shape not just public opinion, but also government policy. And more often than not, the mainstream media is letting Indigenous Australia down.

‘Still selfish, still a rabble’ declared a Herald Sun headline last May after a peaceful protest against the planned closure of remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia briefly shut down Melbourne’s CBD. For Jennifer Nixon, who works in Indigenous media, this is familiar rhetoric.

Nixon was born in Alice Springs, to the Anmatyerr, Kaytetye and Alyawarr peoples, and says Aboriginal issues are still not being properly reported in Australia.

‘It’s just sad watching the mainstream news,’ she says. ‘If there’s an Indigenous issue, you can sort of predict how they’re going to cover it, and you think: “here we go again”… Aboriginals are all painted as dole-bludgers, as wife-beaters or lazy, dirty.’

For Nixon, these stereotypes have turned her into a self-confessed ‘workaholic’.

‘Because I’ve got something to prove, you know … I’m the type that if I go in a room and use something you wouldn’t even know I’d been in there because you’ve got to tidy it all up. It becomes obsessive after a while but that’s just how you’re raised.’

The media construct of Indigenous people as ‘lazy, entitled’ began to emerge during the 1980s, as the mining industry’s publicity campaign against Indigenous land rights came into full force. Media-friendly grabs like ‘the black arm-band view of history’, the ‘surrender Australia policy’, ‘special privileges’ and the ‘Aboriginal Affairs Industry’ crept into the discourse.

As the then Hawke government proposed legislation for land rights, people such as mining magnate Hugh Morgan, historian Geoff Blainey and former Prime Minister John Howard sold their own narrative of injustice – that of a mainstream Australia being passed over for ‘special interest groups’.

Add to this story the other common media image of violence and alcohol in remote Aboriginal communities and the message sunk even further. A 2014 survey of 335 media reports on Aboriginal health found 74 per cent were negative, with many of the most common subjects relating to alcohol, child abuse, petrol sniffing and crime.

In 1991, the year I was born and just 28 years after pictures of those ‘wild tribes’ were printed in the Age, the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody issued a rebuke to the media. In his final report, Commissioner Elliot Johnston QC wrote of the media’s tendency to construct ‘Aboriginal people as a “problem”’. He cited case studies, such as the increasing use of the word ‘riot’ in stories involving Aboriginal people. He spoke of his own conversations with Indigenous Australians:

They considered that their achievements were very seldom given any prominence even if noted at all. […] Antisocial or unlawful behaviour, on the other hand, were given much publicity. If a non-Aboriginal youth was charged with stealing a car the report announced that ‘a youth aged sixteen was charged’, but if the youth was Aboriginal that fact was stated.

Three years later, a study found a majority of Indigenous participants thought mainstream newspapers ‘failed Aborigines dismally’. No major newspaper at the time had an Indigenous Australian as editor.

Today, the situation is little better. According to academic and former journalist Michael Meadows, who has researched Indigenous representations in the media extensively, it may even be getting worse.

‘It’s changed but I don’t know whether it’s necessarily changed for the better,’ he says. ‘Indigenous issues in Australia have become more invisible. It’s not talked about very much and people are more careful about how they talk about things – well apart from Bill Leak!’

Coverage of stories related to Indigenous people also tends to be selective. ‘Out of sight out of mind, if they can help it,’ Nixon says.

In August, when a white man in Kalgoorie was charged with running down and killing fourteen-year-old Elijah Doughty in his car, most of the story’s coverage came after subsequent riots broke out.

‘And that’s what they focussed on,’ Meadows stressed, ‘the rioting.’

For Meadows, this absence of debate on Indigenous issues is an ‘insidious’ new trend:

Simply talking about problems through the media without offering solutions does no good. Communities are so sick of it …but Indigenous affairs just aren’t on the radar anymore. In the early 90s, I remember going to conferences around improving media coverage, I remember Marcia Langton getting up and saying ‘we’ve been talking about this since the 60s and nothing has changed’. Of course, it has changed. It’s not as blatant now, it’s indirect; it’s happening by exclusion, by choice.

Those choices include deciding whose voices are heard – and whose aren’t. It is still not uncommon in Australia to read a story on an Indigenous issue without an Indigenous voice present in the reporting. Often, non-Indigenous Australians stand in for Aboriginal perspectives, as experts or advocates.

At other times, Aboriginal comment might be compartmentalised down to just a few ‘loud voices’, as Meadows calls them, the same spokespeople and well-knowns. Noel Pearson, for example, is a favourite source for journalists, but his views in no way represent all of Indigenous Australia. And how could they?

Nixon says the media tend to rely on the same voices because ‘they use the same terminology that white people can relate to’.

They pick the same hit list, as we say … And the thing is there’s no one answer … there’s so many different layers, so many different Aboriginal clans and groups … and the layers within those groups are huge, you know I’m a 49-year-old Aboriginal woman and I’m still learning.

Fortunately, there is one place where Indigenous voices are heard – our Aboriginal media industry is thriving.

‘It’s really largely because of that negative representation that people said “well bugger you, we’re going to do it ourselves”,’ says Meadows. ‘Really, it’s one of the best kept secrets of Indigenous Australia.’

Today, media platforms like SBS’s National Indigenous Television (NITV), The Koori Mail and indigiTUBE are putting Indigenous people back in control of their own stories. In the 90s, Nixon worked at Imparja Television and saw its impact on communities first-hand. ‘It gave power back,’ she says.

As for the mainstream media, while there have some been some steps forward, there have also been ugly reminders of the steps not even attempted.

Last month, the Press Council ruled out taking action against The Australian for Bill Leak’s cartoon, despite receiving more than 700 complaints. This month, however, the Human Rights Commission launched an investigation into the cartoon for ‘racial hatred’.

‘It’s a reminder that racism is never really far below the surface here, if you scratch hard enough,’ Meadows says. ‘I think the spectre of colonialism is always with us.’

While the current system of media self-regulation may not be sharp enough to cut out the rot of institutionalised racism, there are still certain policies that can be better. Australia’s Broadcasting Services Act, for example, fails to acknowledge the importance of Indigenous culture and language.

‘They have that in New Zealand and Canada; it should have happened here 20 years ago,’ Meadows says. ‘And yes, there’s bigger fish to fry in terms of reconciliation but things like that are symbolic, they say “we value this” and therefore media corporations have to take note.’

Nixon, too, remains disappointed with the daily news cycle.

‘You think it would be a lot better now because the media’s everywhere but it just doesn’t seem to have improved much,’ she says ‘You see a few journalists try to reach out and capture the real stories, which is nice, but it’s sort of still not enough; it’s still in the dark corners of the room, those conversations.’

I think back to four faded photographs, published in 1963. What did the people behind them think of the way they had been depicted, of ‘the brush and the comb’, of genocide swept under floorboards?

‘The media is a powerful institution,’ Commissioner Johnston wrote in 1991. ‘It is a power that must be shared, not in kindness but in justice, with Aboriginal people.’