Is there anything left to say about the current arts funding crisis in Australia? Many writers have already covered the ins and outs: Esther Anatolitis on what next; Kate Larsen on the danger to literature in particular; Alison Croggon’s summary of the past couple of years, ‘Black Friday’; Anwen Crawford on the importance/devastation of youth arts funding; David Berthold on changing our funding demands; ‘Love, anger, money’ by Gillian Terzis at The Lifted Brow; plus countless other pieces from various theatre-makers, actors, dancers and peak bodies.

There was also our petition to George Brandis last year, signed by hundreds of artists, after he cut $105 million from the Australia Council to establish his own slush fund; and our petition from 2014, too, which was organised by literary magazines and also signed by hundreds of artists, when the government announced the first round of cuts to the Council in conjunction with a horribly grim budget. More recently, we published Ben Eltham’s searing indictment of the way funding is distributed, ‘The excellence criterion’, and of course Alison Croggon’s much cited, ‘Why art?’

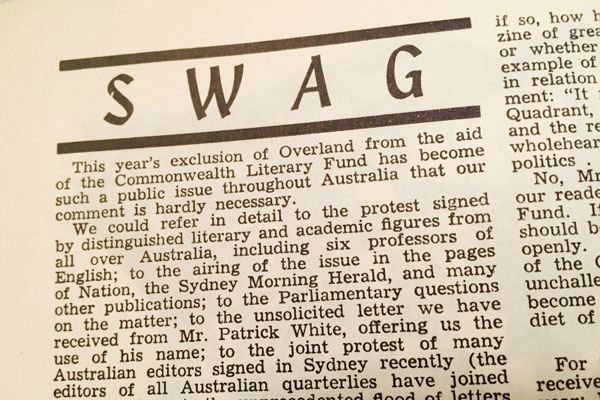

But we have always had to fight for arts funding. Decades ago, artists and writers ran a long and bloody campaign to establish what is now the Australia Council model, a fight Overland’s founding editor Stephen Murray-Smith was very involved in, as his litany of editorials devoted to the problems with literary funding attest.

I agree with Kate Larsen that literature is especially endangered right now: the arts have been underfunded by successive governments, and literature has always received, in the words of Stephen Murray-Smith, the least ‘superphosphate’. In part this is because we’re not really seen as an art form, given the commercial publishing market (as if a literary magazine could compete with a publication like The Monthly), but also because we run on extremely slender budgets and a helluva lot of volunteer labour. Nevertheless, I would argue, we are the most efficient of all the forms, with every cent going into producing more and more new work.

Arts funding is something that should be a given in Australia, a social necessity. In a true democracy, we would see more funding for areas that benefit people – health, education, arts, science – instead of submarines and offshore torture camps. Overland was lucky in an extraordinarily restrictive funding round – but given the calibre of the many excellent organisations that missed out, luck is all it feels like.

History is no doubt an advantage when it comes to funding and longevity, as we can see through the many authors reminiscing about Express Media and Meanjin, and how those organisations helped them develop their craft, or offered them the space to contribute to Australian culture. History can be a hindrance too, as Terzis writes:

‘Investment in arts,’ Gough Whitlam once wrote, ‘will produce a fair amount of dross’. ‘It will attract its fair amount of charlatans and mediocrities.’ He wasn’t wrong. Grant culture can be stultifying. It can keep obsolescent publications afloat for far longer than their natural shelf-life. It can deter people from taking risks.

But what does it mean for a publication to be staid? Presumably staid publications have no readers, but that’s hardly the case for any of Australia’s literary magazines. There will always be journals that take fewer risks, but while funding may reward some levels of repetition, it can also provide the space to support other kinds of writing. This, more than anything else, is an argument for more funding: we need a wide variety of literary magazines healthy enough not only to be able to pay writers and editors, but also to challenge what it means to produce Australian literature in 2016 and 2017 and beyond.

Of course it is important to subscribe to literary journals. Perhaps you love the Australian textual landscape, whether poetry, fiction or essay. Or maybe you want to participate in that publication; maybe you simply want it to continue. But we can’t reduce the value of literature and literary journals to that of the market. The market can’t replace the fact that literary culture is not a competitive product. And perhaps it’s not a product at all, but a space.

Funding creates a space for artists and writers to push against the literary edges, to experiment – something that’s hard to measure, involves a high risk of failure and thus so rarely seen as a ‘good investment’, and yet it is imperative. In many ways, the literary landscape is always on the edges, because literary culture is a niche passion. Funding has allowed Overland to publish electronic poetry and experimental fiction, create our inaugural residency, run literary competitions, and publish more than 450 new works a year. As of 2017, we’ll also be able to pay writers more. But we need a diversity of publications and of writers – culturally, formally and in terms of content. No one publication can do everything and nor should it. That would presume we are all identical and would weaken our cultural imaginings.

‘I would like to think that the present Meanjin is a lineal descendant of all that has gone before,’ Jim Davidson wrote to Clem Christensen in 1982. I feel similarly about Overland. Even today, we are guided by our founding editorial message, penned by Stephen Murray-Smith in 1954:

The magazine will publish poetry and short stories, articles and criticism by new and by established writers. It will aim high … [but] will make a special point of developing writing talent in people of diverse backgrounds. We ask of our readers, however inexpert, that they write for us; that they share our love of living, our optimism, our belief in the traditional dream of a better Australia.

Nowadays I replace ‘Australia’ with ‘world’, skimming over the nationalism, but that’s our history, and it tracks the ways culture shifts and transforms too.

During the Cold War, governments saw culture as important to the public, and to a society’s perception overseas. Culture was a battleground – in some ways, it still is, even if the CIA is no longer interested in literary journals. Under the current Australia Council model, arts funding is competitive, as it has been for a number of years. There are many brilliant literary organisations that did not receive key organisational funding, even though they’re key to the Australian textual landscape (which is not to say they all applied): Australian Poetry, Mascara, Rabbit, The Lifted Brow, Westerly, Southerly (Australia’s oldest journal), Island, Peril, Cordite, Meanjin, Going Down Swinging, various literary festivals. But it’s worth remembering that funding under the Australia Council is distributed through a peer-review process. The Council has a limited amount of money, and a panel of our literary peers decide where it goes. It’s not a perfect system, but it is an attempt at a democratic one, and a markedly different process to the Catalyst fund, decided by ministerial or bureaucratic discretion.

Ideally, every literary organisation with an audience and an established identity would be funded. Perhaps it could be scaled, depending on the size of the organisation and its needs, but it would guarantee a literary culture that spans cultures and forms and styles and content. At the moment, however, all literary journals are not equal. Right now, it is much harder for newer or daring publications to secure funding. Some publications have institutional support, while other institutions are happy to pay millions for buildings or vice chancellor salaries, but won’t contribute loose change to continuing a thriving literary culture.

Like everyone else in the arts, I worry about the lack of support for new forms and ideas and aesthetics in the years to come. I am particularly concerned for poetry – a challenging art, one that cares as much about language and form as it does content, that will never survive in the marketplace. Yet in my time at Overland, I’ve also noticed that poetry is the most inclusive form – the most likely to attract women and working-class writers and writers of colour, and experimental writers too. Cordite Poetry Review, for example, has been producing amazing work for almost twenty years. It is a hotbed of poetic experimentation and talent – and it’s fabulously collaborative. Where will poets be if Cordite doesn’t survive the next couple of years?

We can’t fix this by subscribing to one publication. The answer is to fight – again – for a bigger, more just funding model. It is a political fight, because we pay taxes and we deserve them to be spent on the research and production of culture. And it is a fight that matters because art should not simply be something for the wealthy to create and applaud. #FreetheArts

P.S. Email overland@vu.edu.au if you want to be involved in such a fight.