Last month I received a legal letter accusing me of defamation. Someone who was very close to me for many years – but now is not – had read a piece of short fiction I had published and decided a minor character was about them.

Fiction, writes Frank Moorhouse, is ‘woven out of the life that the fiction writer has led’. Like every writer ever born, I have gleaned sentences, character traits and events, and I’ve hodgepodged it all together to try and convey an emotional truth. It’s what we do, right? Surgeons gonna cut, haters gonna hate and writers gonna glean.

‘If you’ve been told a story by a friend or something happens in your family,’ said novelist Julian Barnes, ‘it’s all fair game.’

Never once had I considered defamation.

‘What the hell?’ said my friend when I rang him in a panic. ‘It’s fiction.’ And another argued: ‘Then what about Helen Garner? Surely, if you can get sued that easily in Australia then she would have been!’

After I cried, I pored over the Defamation Act online. Firstly, what actually is defamation? According to Arts Law, it is ‘the publication of statements that lower the reputation of a person in the eyes of his or her community.’

Luckily, whatever we publish in Australia, no-one is going to jail us for it. There hasn’t been a case of criminal defamation in Australia since Frank Hardy’s 1950 book, Power Without Glory – a brazenly fictionalised version of real life events in Melbourne – was published and he was unsuccessfully prosecuted.

The only recourse for people who believe they have been defamed by a work of fiction – the plaintiff – is civil defamation, with the hope of getting damages, an apology, or a good pulping. The plaintiff must hire lawyers, begin legal proceedings within a year of the publication of the work of fiction, and prove three things:

- that the fiction has been published to a third person

- that the fiction identifies (or is about) the plaintiff; and

- that the fiction is defamatory.

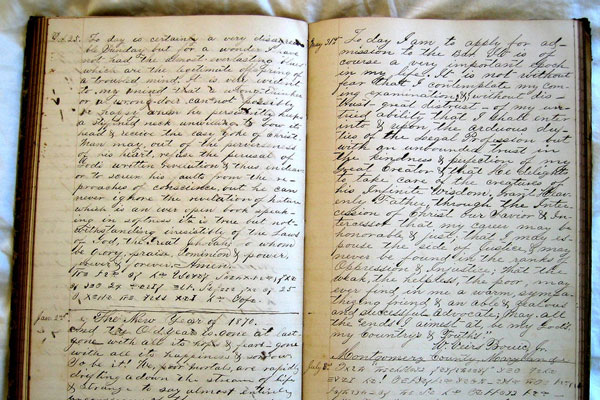

A book or a journal or a magazine is clearly ‘published to a third person’, but if you write a short story in your diary brutally slagging your old boss, you should be in the clear. But, in this era, online is ‘published’ – even social media.

It’s easier for the plaintiff to prove the second point in a piece of non-fiction, obviously. Fiction is where it gets blurrier. As writers we can write what we want, smug like lords of the page, if we just change the names, right? Nope. Writes Frank Moorhouse:

We like to kid ourselves that that by changing the name of one of our friends called Donald Day to Donald Knight [will keep us out] of the courts. It’s possible [that] no matter how much disguise you lay on a real person and put them in a novel, if there are people who can recognise him or her you are still [liable]. . .

According to Melbourne barrister Justin Castelan, who runs the blog Defamation Watch, ‘if the person can be identified by a reasonable person with knowledge of extrinsic facts’ then you could be liable no matter ‘what specific differences have been applied’.

So, what do writers who want to base fictitious characters on real people in Australia do? They change the gender, they split one character into six, they ask for permission to publish and they ‘leap and skim, compress and conflate things’.

Finally, the plaintiff must prove that it’s defamatory – that [the work]:

. . . contains imputations that:

- have a tendency to lower the plaintiff’s estimation in the eyes of right-thinking members of the society generally; or

- were calculated to injure the reputation of the plaintiff by exposing him or her to hatred, contempt or ridicule;

- have the capacity and tend to put the plaintiff in the position of being shunned and avoided.

The legal letter I was sent threatened to sue me if I ever wrote anything about the person, our relationship, the end of our relationship or that person’s new relationship.

Luckily, I discovered that no-one can prevent you writing about them just because they don’t like it. The laws of defamation, although an ‘inherently uncertain area of law’, according to Justin, were not designed to control and stifle creative expression. They are ‘an attempt to balance the protection of two contrary values, reputation and free speech’.

If the plaintiff proves all of these things and you end up in court, there are several defences available. For example, if the plaintiff can prove that the fictitious character you created is based on them, and that what you have written is defamatory, but you can prove that it’s based on factors that are ‘substantially true’ you have a solid defence. Because, and listen close to this bit, it’s not defamation if it’s true, no matter how awful it is, or how much the plaintiff doesn’t want fiction based on it in the public domain.

So, if you write a novel about a philandering professional golf player called Tiger Woods (or Leopard Forest), and he sues you, you have a good defence.

Whilst researching this piece, I struggled to find any cases of defamation in fiction in Australia, bar a handful many decades ago. Lawyers I spoke to echoed this. There are many reasons for this. ‘Courts,’ an arts lawyer friend emailed me, ‘are big supporters of free speech, and are usually very reluctant to interfere with it. They’re also reluctant to get involved in petty disputes about reputation – it usually has to concern a matter of pressing public interest for them to take an interest in censoring someone.’ In her opinion, ‘not many “right thinking” people would be bothered to take a defamation action to trial.’

Suing someone for defamation is also prohibitively expensive. ‘It can cost in the hundreds of thousands of dollars,’ said Castelan. He couldn’t think of an example in fiction, but mentions Joe Hockey, who won a defamation case against Fairfax and was awarded damages of $200,000. However, as ‘Fairfax was only ordered to pay 15% of Hockey’s legal costs, it is almost certain that it cost Hockey more than he received.’

Suing for defamation can also backfire. The plaintiff ‘put[s] their own reputation in the witness box,’ said Castelan. ‘If there is any shred of truth in the allegations that are published, then the impact of a trial in court and all of those allegations getting ventilated publicly, possibly with further media exposure, is massive on the person who sues.’

Frank Moorhouse – himself no stranger to legal threats from people from his past – argues against writers pre-censoring our work, claiming that ‘the contract of the writer is not with his friends and intimates and workmates and with living people around him, his primary contract is with the reader, and the reader/writer contract is that the writer promises to share with the reader what he or she, the writer, has experienced of the human condition.’ He quotes William Blackstone who argued in 1769 that every free person is allowed to ‘lay what sentiments he wishes before the public’. But if he publishes anything ‘improper, mischievous or illegal’ then he must ‘take the consequences’.

With a bit of smarts and editing, it’s not too hard to respect our contract with the reader and avoid legal consequences. If writers understood defamation laws a bit better, with a bit of tinkering, Arts Law reckons we could all publish many things we’re holding back on ‘without fear’.

So, read the Defamation Act. Befriend an arts lawyer. Talk to the Arts Law Centre of Australia and read their handouts. And if you’re threatened with legal action for a piece of fiction you’ve published, don’t panic. Most threats are just bluffing. But if you receive a ‘statement of claim, writs or summons’ get legal advice, says Justin Castellan. ‘It will not go away and if ignored will get far worse.’

I don’t believe I’m liable for the story I mentioned, and now that I’m clued up on defamation in Australia, I’m not anxious I ever will be.

Please note: this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

—

If you liked this article, please subscribe or donate.

Image: Barnaby Dorfman/Flickr