In the last three weeks we have seen the emergence of a new and seemingly powerful campaign, arguing that 267 asylum seekers who were party to a failed High Court challenge, should be allowed to stay in Australia. Coming together under the slogan Let Them Stay, thousands of people across the country have attended rallies, blocked traffic, occupied offices, executed banner drops and shared photos of themselves and their workmates opposing the deportation of these people. Most recently, Lady Cilento hospital in Brisbane emerged as a major flashpoint as doctors and nurses there refused to let baby Asha, who was in their care, be released for deportation. A spontaneous round-the-clock community picket emerged which aimed to both physically and symbolically block the immigration department from seizing Asha. As of Monday morning, it seemed that this action was in part successful: Peter Dutton announced that Asha and her mother would be placed in community detention. But he was clear this reprieve would be temporary. When it is deemed appropriate, they will be removed to Nauru.

While it seems too soon, and too inaccurate, to declare victory, the protests demonstrate that collective action can impact on government decision-making. However it puts new pressure on the limits of the slogan Let Them Stay. Baby Asha’s imminent deportation has been halted, but the struggle is far from over. What are the politics, potentials and pitfalls of Let Them Stay? How could we go from this moment – which is but one in a long history of opposition to the actions of Australia’s Immigration Department – to a broader dismantling of Australia’s racist border regime?

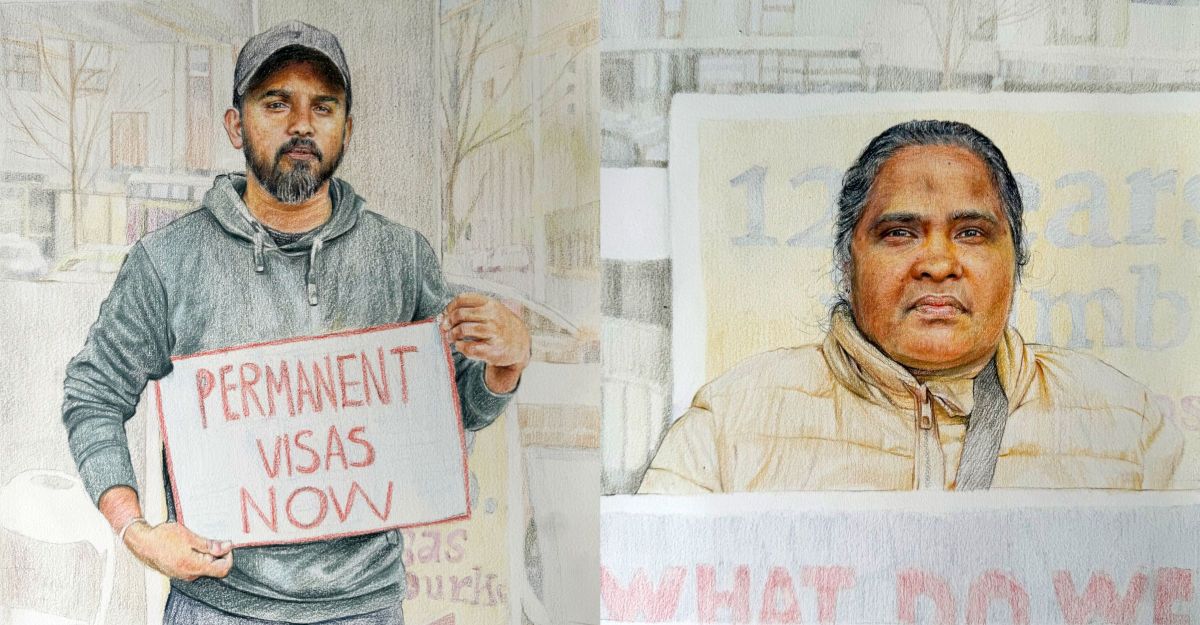

Despite criticism from people and organisations such as RISE, a large section of those who have mobilised under Let Them Stay have focused on the children who are liable to be deported to Nauru. Children have been central to the argument for everyone from the Greens, to protesters at Bondi Beach, to comedians, to Victorian premier Daniel Andrews, and everyone in between. This follows from actions over the past few years, which have seen activists initiate a myriad of campaigns aimed at freeing asylum seeker children. As Osman Faruqi recently suggested, despairing of bipartisan support for the ongoing detention system and hard-line border protection policies, activists have decided that pulling on the heartstrings of both the public and politicians with a campaign focused on children in detention will garner the most sympathy. There has been an increase in campaigns focusing on child asylum seekers generally, with the reformation of ChilOut, the formation of groups like Grandmothers Against Detention of Refugee Children, and the focus from international sources such as the Lancet medical journal, on the harm detention causes only to children. For many of these groups, the argument is that this a strategic focus, aimed at mitigating the worst effects of the detention regime on those most physically and psychologically vulnerable. They also suggest that getting children out of detention is the thin end of the wedge of the gradual dismantling of the system.

The focus on children leads to a perpetuation of a discourse around asylum seekers that is ultimately damaging to longer-term aims of dismantling the border regime. Children are chosen as the figureheads of campaigns like Let Them Stay because they represent an unquestioned innocence. Refugee activists use these images of children, both because they seem to easily elicit feelings of sentimentality and pathos, but also because they are seen as appealing to the lowest common denominator, connecting with broad layers of people on the basis of a common humanity. In these discourses, children are positioned as absolutely innocent, fully deserving of pity and care, while adults are erased, or figured as not worthy of the same degree of care and sympathy. If we think internationally, we can note, for instance, that the current definitions of a combatant held by the US when perpetrating drone strikes is any man of military age. These definitions float across borders, so that when people seek asylum, the children are seen as innocent, the adults as always already guilty.

Campaigns that focus only on children further perpetuate this guilty/innocent dichotomy, imagining that it’s possible to present the issue through an apolitical, humanitarian and moral lens. This focus on the innocent child thus contains many risks, blindspots and erasures. In a recent text, Ilana Feldman and Miriam Ticktin write that the images of children which circulate in these and other similar discussions are deeply superficial. They suggest that ‘when only the absolutely innocent elicit care, giving, and empathy … our solidarity and ability to create lasting peace remains dependent on a mirage and thus easily thwarted.’

A focus on children can produce moments such as when Queensland premier Annastacia Palaszczuk joined calls to halt the deportation of Australian-born asylum seeker children back to Nauru by asserting ‘it’s about time we put politics to one side.’ But instead of putting politics to one side (as if that were ever possible), we suggest a need to re-centre serious political claims. While groups such as GetUp!, under the pretence of leading the Let Them Stay movement, have preferred to stick to key talking points based around the vulnerability of asylum seekers, the movement on the ground has taken a different shape.

The protests in Brisbane already evince the amorphous politics of Let Them Stay. When local MP Terri Butler attempted to address the gathered crowd she was drowned out by cries of ‘shame, Labor, shame!’ – a clear indication that the crowd did not trust her motivations. Rather than accepting her endorsement of the struggle to let baby Asha and others stay, the protesters took the opportunity to make a much wider critique of the major role played by the ALP in setting up and perpetuating our current system. Anecdotal accounts are emerging of new relationships of solidarity being formed outside the hospital and the radical reuse of urban space represented by the community picket.

A striking quality of recent rallies has been the widespread calls for civil disobedience and noncooperation. These calls were taken up enthusiastically by the assembled crowds. When people are ready to break the law, they are also ready to question further fundamentals of our society, to build on the existing momentum towards a deeper politics and stronger commitment to vast change.

While some claim the participation by the union movement in the campaign is hypocritical as their super funds are still invested in detention centres, Let Them Stay has also seen union members and activists step up in an unprecedented way. From the Victorian Trades Hall being offered as a place of sanctuary, to the ongoing bravery of nurses and the ANMF, to the central role of unions in mobilising, organising and promoting the Brisbane picket. The possibilities for building on this represent huge potential: on top of the refusal of nurses and doctors to release asylum seekers back into detention, we may see forms of industrial action aimed at halting the machinery of the detention system.

Civil disobedience, non-cooperation and industrial action force us to assess how our everyday lives are inextricably caught up in producing and reproducing systems of oppression and exploitation. They also illustrate our power to intervene in these systems and force societal change.

How then can we take this slogan and make it part of a longer and larger struggle? It would seem that for a campaign to be successful in creating long-term change, a serious reckoning with racism, colonisation, and the racialised technologies of border control needs to take place. How can different ideas of what it means to stand alongside others – in solidarity, rather than through humanitarianism – be developed? Projects of decolonisation can provide a political guiding force for campaigns in solidarity with migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. This is a point made by numerous people, such as RISE, Philly and Clare Land.

Positioning campaigns as pleas for moral or national redemption, regaining international respect, or simply humanitarian requests for pity and human rights will always be a fatally limited approach. We need to struggle to change the structures of our societies, to dismantle the racism that produces and is reproduced by our immigration system, in solidarity with the asylum seekers and refugees who continually challenge the border regime.

Part of decolonising our political practice involves not taking as natural and inevitable the divisions created by the nation-state. If we are to make our movements of solidarity truly transnational, our calls for change, for letting people stay, should not be directed solely towards our particular governments. By rethinking the ways in which we organise our political claims, we could, indeed, create new ideas of what it means to ‘stay’.

—