The presidential debate as a Baudrillardian simulacrum? There would be little, it seems, to take issue with here. If the simulacrum marks the point at which, rather than being a mere copy of the world it represents, the realm of media imagery becomes the world we live in, then it has found an exemplary model in the contemporary phenomenon of the televised political debate.

Since Nixon’s sweaty jowls purportedly lost him the 1960 election, presidential debates have been marked by the supremacy of visual presentation and, concomitantly, the determined absence of political content. If anything, the party primary versions are even more denuded of substance. Devoid of any significant confrontation of ideologies, these debates are purely stage-managed affairs that serve only to crank up the whirligig of speculative punditry in the mainstream media, at the end of which process one among the ranks of perfectly interchangeable candidates is churned out to be the party’s nominee in the final duel.

In this sense, 2015’s sprawling Republican debates have conformed impeccably to the program. Over the course of four sessions, the GOP’s multiplying swarm of would-be nominees have tussled with each other over a set of issues that ranged from the dangerously demagogic (Trump’s enduring proposal to expel all illegal immigrants and erect a wall on the Mexican border) to the self-parodically obtuse (Carson’s claim that the pyramids were used for storing grain).

What reason was there for their Democratic counterparts to be substantially different? Indeed, everything in the build-up to the first Democratic debate on October 13 conveyed the impression that it would unambiguously play the role of a simulacrum of political discourse, dominated, as with the Republican debates, by pompous grandstanding, petty personal point-scoring and phony dissension on policy.

For a start, the event was held in a glitzy Las Vegas casino, packed with an excitable audience of party loyalists and wealthy donors, and festooned with the corporate logos of the function’s co-organisers, CNN and Facebook. This tone was heightened by CNN’s broadcast, which presented the proceedings along the lines of a heavyweight title bout or Hollywood blockbuster movie. Over soaring orchestral music and hyperactively edited imagery of the candidates, a booming voice over intoned, ‘In the heart of Las Vegas right now, a marquee event. A high-stakes clash of campaign rivals who have never gone head-to-head before. It’s the Democrats’ turn in the spotlight, with the White House on the line.’ The voice over proceeds to label Hilary Clinton ‘the party superstar who’s been down this road before’ and Bernie Sanders ‘the surprise threat, gaining in the polls despite critics who doubt he can go the distance,’ before tokenistically noting that ‘three other political veterans [Martin O’Malley, Jim Webb and Lincoln Chafee, all polling roughly 1% at the time] are also in the mix.’

A curious thing, however, happened once the debate was underway. Even during the candidates’ introductory remarks, it was clear that, in terms of both style and substance, a gulf separated Sanders from his sparring partners. Instead of the pat personal stories, confected folksiness and vacuous sound bites peddled by the other candidates, Sanders launched into a bristling diatribe against wealth inequality, Wall Street, campaign finance and climate change, and called for a popular mobilisation to ‘take back our government from the handful of billionaires and create the vibrant democracy we know we can and should have.’

It was when the question-and-answer session commenced, however, that the political real truly pierced through the veil of the televisual simulacrum. After Clinton – in many ways, a human embodiment of Baudrillard’s notion of simulation, with a persona carefully cultivated by her bulging campaign team – had been interrogated on her shifting positions on issues such as marriage equality, the Keystone oil pipeline and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, moderator Anderson Cooper’s attentions were turned to the Vermont independent: ‘Senator Sanders, a Gallup poll says half the country would not put a socialist in the White House. You call yourself a democratic socialist. How can any kind of socialist win a general election in the United States?’ Unflustered, Sanders answered that the levels of income disparity in the US and its lack of free health care and higher education were ‘morally wrong’, and argued that ‘we should look to countries like Denmark, like Sweden and Norway, and learn what they have accomplished for their working people.’

When Cooper pushed for confirmation as to whether he considered himself a capitalist, Sanders’ indignation was unbridled: ‘Do I consider myself part of the casino capitalist process by which so few have so much and so many have so little, by which Wall Street’s greed and recklessness wrecked this economy? No I don’t. I believe in a society where all people do well, not just a handful of billionaires.’ In an extraordinary turn, the CNN host then asked if there was anybody else on stage who was not a capitalist. A cut to a wide shot showed a momentary, eerie silence among the other candidates, frozen in paralysis at how to answer this question. Eventually Hillary Clinton piped up to speak in favour of ‘saving capitalism from itself.’

For the first time in the modern history of the United States, a nationally televised presidential debate revolved around the relative merits of capitalism and socialism. More remarkably still, one of the candidates vigorously defended the latter side. Sanders has been in electoral politics for three decades, and has openly called himself a socialist throughout, even in the long period after the fall of the Berlin Wall during which any professed belief in a socialist alternative to global capitalism was summarily ridiculed. Although Sanders tends to identify with an idealised version of the Scandinavian welfare states of the 1970s rather than the revolutionary socialism of the Marxist tradition, even this vision is so remote from mainstream political discourse in the US that he is generally viewed inside the Beltway as a crackpot hangover from the 1960s hippie movement, whose rise to the senate was only possible in the oddball state of Vermont, a mostly-rural liberal enclave in the far north-east corner of the country.

His presidential run, however, has exploded the decades-long taboo against the s-word on the national political stage (even Ralph Nader shied away from using the term in his 2000 and 2004 campaigns), revealing in the process that there is in fact, a large constituency of Americans for whom a candidate unabashedly identifying as a socialist and calling for a ‘political revolution’ is attractive. Polling has shown him to be within touching distance of Clinton’s once impregnable lead, especially in the key early primary states of Iowa and New Hampshire, his campaign fund has drawn more than 700,000 donors contributing an average of around $30 a head (while unrepentantly eschewing the Super-PAC model of campaign financing), and rallies featuring Sanders have garnered turnouts of up to 25,000 people in major cities across the country. Such success for a candidate this far to the left of the ideological spectrum would have been unthinkable even four years ago. The CNN debate, meanwhile, allowed the senator to spend a combined 30 minutes of broadcast time articulating a progressive alternative to the neoliberal consensus in front of an audience of 15 million viewers.

Coming out of the debate, focus groups and online polls – never, admittedly, the most ‘scientific’ of measuring devices – overwhelmingly favoured Sanders as the best performer on the night, while he also attracted the greatest interest from Google and Twitter users. To no avail: the media commentariat unanimously anointed Clinton the debate’s ‘winner’, and if Sanders was discussed at all, the focus lay not on his denunciations of finance capital and the corrupted political system, but his declaration that the American people were ‘sick and tired’ of hearing about Clinton’s ‘damn emails’. Perversely, even Sanders’ principled unwillingness to stoop to personal attacks against his rival was seen as a bonus for the Clinton campaign.

Of course, the pundit class could not but judge Clinton to have carried the day, because its entire system of judging candidates conforms to the superficial demands of the political simulacrum, which largely ignores the content of what the contenders are saying in favour of evaluating presentation and performance. Do the candidates retain a suave, poised demeanour, avoiding any obvious blunders? Do their sound bites stay ‘on message’? Can they artfully dodge the thorny questions inevitably thrown up by their various hypocrisies? By all these measures, yes, Clinton ‘won’, and continuing in this vein will most likely ensure that the inertia of her institutional dominance within the Democratic machine withstands the Sanders insurgency and delivers her the nomination. In terms, however, of radically transforming the ideological terrain of the nation, and the very parameters of contemporary political discussion, Sanders has already achieved more than he and his allies could have possibly hoped for when his campaign was launched six months ago.

But the simulacrum had another card up its sleeve, albeit a relatively benign one. Since at least 1992, when Dana Carvey as Bush Sr and Ross Perot squared up against Phil Hartman’s Bill Clinton, the Saturday Night Live debate parody has become an integral ingredient in the US electoral process, so much so that prospective candidates now deliberately tailor their public image with their prospective imitation in mind, and even take to appearing on the show in person to prove that they are in on the joke – witness, on an episode earlier this year, Clinton’s cameo alongside her parodic self (Kate McKinnon, creditably rendering the candidate as a psychotically driven political robot).

While SNL’s political impersonations have not always hit their mark (the show has never really been able to get a handle on Obama, for instance), at their most effective, they define the nation’s collective memory of the politicians the show satirises: think the 2000 debate with Darryl Hammond as Gore (‘lockbox’) and Will Ferrell as Bush (‘strategery’), or Tina Fey’s celebrated 2008 spin as Sarah Palin (‘I can see Russia from my house’ – a line now often erroneously attributed to Palin herself).

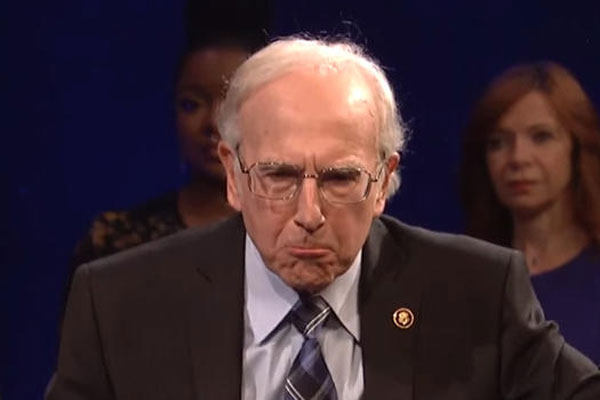

The SNL take on this year’s first Democratic primary, therefore, was keenly anticipated. Few, however, expected the coup de grâce that ensued: Larry David, briefly a writer for the show in the mid-1980s who would later go on to phenomenal success with the shows Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm, strode up to the podium and delivered a pitch-perfect rendition of the Vermont senator. A recurring role as the voice of George Steinbrenner on Seinfeld aside, David has never been known as a gifted impersonator, but for this assignment he had no need to be. Online, many had already remarked on his uncanny similarities with Sanders. Seeing, therefore, a dyspeptic David-cum-Sanders exclaiming, ‘I’m gonna dial it right up to a ten. We’re doomed! We need a revolution! Millions of people on the streets! We gotta do something, and we gotta do it now!’ amounted to experiencing a kind of comic sublime.

This was continued as the sketch took a surreal, but satirically peerless, twist, with David/Sanders veering into a rambling discussion of his outsider status and the penurious state of his wardrobe: ‘I’m the only candidate up here who’s not a billionaire. I don’t have a Super PAC, I don’t even have a backpack. I carry my stuff around loose in my arms, like a professor between classes. I own one pair of underwear, that’s it. Some of these billionaires, they got three, four pairs. And I don’t have a dryer. I have to put my clothes on the radiator. So who do you want as president? One of these Washington insiders, or a guy who has one pair of clean underwear that he dries on a radiator?’

The segment was immediately picked up by a gleeful media, and has since been viewed more than seven million times on YouTube. Instantly, Sanders’ campaign became entwined with the performance of his comedic alter ego. As a precursor, one thinks of Fey’s uncanny resemblance to Palin, but in that case the similarities between the two were limited to their appearance – in terms of personal backgrounds and political views, they could hardly have been more antithetical, and Fey contributed more than a little to the torpedoing of Palin’s career.

The identity shared by Sanders and David, by contrast, goes deep: the two balding, aging, famously cantankerous men were both born to Jewish families in the 1940s, and raised in adjacent neighbourhoods of Brooklyn (Flatbush and Sheepshead Bay respectively). Speaking in near-identical New York accents, they are both prone to bouts of barking irascibility. Moreover, the comedian is also known as a political liberal, and openly supported Obama over Clinton in the 2008 primaries. Although he has refrained from a public endorsement this time around, David’s impression was unmistakably imbued with certain sympathy for his crotchety doppelganger.

While not renowned for his sense of humour, Sanders responded to the send-up with good graces: on the campaign stump the next day, he jokingly suggested that David should join him on the speaker’s platform, and clarified for the press that he had recently bought a second pair of underwear. A few days later, when the candidate was asked what he thought of David’s impression during an appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live, the circle completed itself. Imitating the imitator, Sanders bellowed out the comedian’s Curb catchphrase: ‘Well, I thought it was… pretty, pretty, pretty good.’

David’s curious incursion into the presidential campaign, meanwhile, was repeated three weeks later when he reprised his role on a spoof of the Rachel Maddow-hosted candidates’ forum, and implored voters to donate their ‘vacuum pennies’ to Sanders’ campaign. The comedian, however, made news headlines from a different intervention on the show. As it happened, he was appearing on the same episode that, contentiously, was being hosted by Donald Trump. Anti-racist group Deport Racism had offered a $5000 bounty to any audience member who disrupted the Republican candidate’s performance on the show, and so David duly obliged, yelling ‘You’re a racist’ during the monologue before explaining his strictly mercenary reasons for doing so. Trump’s scripted response – ‘As a businessman, I can fully respect that’ – confirmed that the interruption was, predictably, staged for the show. Not for the first time, a hot-button political issue had been co-opted by late-night television and turned it into toothless comedy.

That such a fate may have also befallen Sanders’ campaign was in evidence in the second debate on 15 November, a low-key affair held in the early-primary state of Iowa. Even with the terrorist attacks in Paris fresh in the memory, the senator steadfastly continued to focus on his core themes of social injustice and Wall Street’s domination of the political process. Talk of socialism, however, was downplayed, with Sanders only raising the term in relation to his proposed taxation system, quipping that he was ‘not that much of a socialist compared Eisenhower’ (under whom the top marginal tax rate was 92%). Already, his discourse had taken on a distinctly less insurrectionary allure than it had possessed in the first debate, and was more smoothly incorporated into the pre-programmed spectacle of the CBS-broadcast debate.

One cannot help but ponder whether David’s SNL impersonation has played a role in defusing the subversive potential of the Sanders campaign, transforming a radical political message into the idiosyncratic quirks of a familiar TV character. Sanders’ unimpeachable personal authenticity and stridently left-wing platform may indeed have shattered the first-order simulacrum – the contrived artificiality of the televised presidential debate – but it appears he is being re-assimilated into the media machine through the satirical second-order simulacrum of the SNL debate sketch.