A week and a half ago, Arts Minister Mitch Fifield announced a new policy for culture in Australia called Catalyst.

In a Turnbullian spirit of agility and innovation, Fifield touted Catalyst as a program that would ‘forge new creative partnerships and stimulate novel ways to build participation by Australians in our cultural life.’

‘Catalyst is intended to support innovative ideas from arts and cultural organisations that may find it difficult to access funding for such projects from other sources,’ the media release enthused. It ‘could include gallery, library, archive, museum, arts education and infrastructure’.

Sound deliberately vague and fuzzy? Indeed. Catalyst was greeted with a short burst of initial enthusiasm by the arts industry, followed by growing unease.

The background to Catalyst is the upheaval in federal cultural policy this year. It all began on budget night in May, when George Brandis announced his ‘National Program for Excellence in the Arts’. The policy aimed to take $105 million off the Australia Council and give it to a new ministerial slush fund, that could disburse art projects more to the minister’s liking than the sorts of things funded by the arms-length art nerds at the Australia Council.

Despite a scruffy exterior, the arts sector is not known for its radical tendencies. But Brandis’ lordly behaviour as Arts Minister, and the fact that the Australia Council funding cuts associated with the Excellence fund threatened to eviscerate hundreds of smaller arts companies, united the sector in opposition.

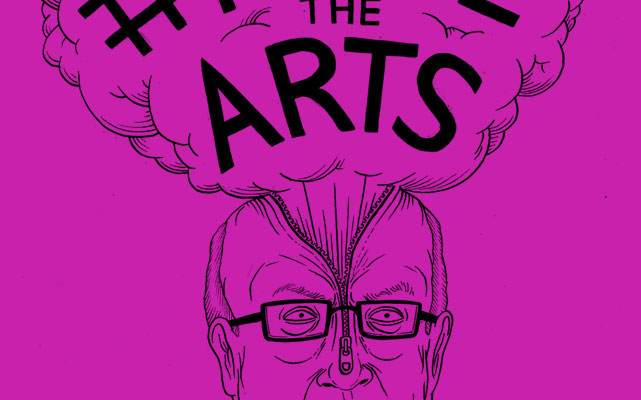

A lively protest movement sprang up, led mainly by the community arts sector, and going under the name ‘Free the Arts’. So successfully did it make its case, Brandis was eventually stripped of the Arts portfolio in Malcolm Turnbull’s new cabinet. Artists thought they had won.

It wasn’t to be. New Arts Minister Mitch Fifield was faced with a difficult situation. The arts sector wanted the Excellence fund killed off, and the money given back to the Australia Council.

But for quite pedestrian reasons of party loyalty, Fifield couldn’t do that.

Fifield still sits with Brandis in the Senate, and in the cabinet (Brandis remains Attorney-General). Brandis is well-known for his long memory and equally long list of enemies. Killing off the Excellence Program altogether may well have started a factional civil war.

So Fifield compromised. He gave $32 million over four years back to the Australia Council, under the pretence that this would protect the smaller arts companies. He then renamed the Excellence fund ‘Catalyst’, a satisfactorily nebulous name.

‘What we’re seeking to do with Catalyst is not to supplant or compete with the Australia Council, but really to complement its efforts,’ Fifield explained to the ABC’s Michael Cathcart last week.

It didn’t take long for the conceit to unravel. If Catalyst was really ‘complementing’ the Australia Council, why was the Australia Council’s funding being cut? If Catalyst was not ‘supplanting’ the Australia Council, why was the Australia Council laying off staff?

As critic and commentator Alison Croggon noted on the ABC, ‘for all the Arts Minister’s soft-soap talk of bridge-building and consultation with an alienated constituency, things remain little different than they did in May this year.’

The consequences for the so-called ‘small-to-medium’ sector – a group of several hundred small theatres, publishers, galleries, dance companies and Indigenous and community arts organisations – remain dire. This is the most vibrant and productive part of the entire arts industry – as figures released by the Australia Council this year show.

And yet, the funding cuts associated with Catalyst mean it is exactly these organisations that are still under the gun. Before the Excellence fiasco, the Australia Council had called for applications for six-year organisational funding for the smaller companies; more than 400 applied. But in the chaos after Brandis’ coup, the entire six-year funding round was abandoned.

Despite Fifield’s emollient assurances, his decision to rebadge the Excellence fund as Catalyst means that funding will not be restored. In its place, the Australia Council is offering four-year organisational funding, with a much smaller funding pool. Many organisations are expected to be defunded.

Applications are due this Tuesday, but funding won’t start until 2017. There will be no opportunity for smaller companies to apply for organisational funding after tomorrow’s four-year round closes. The funded small-to-medium sector is likely to shrink, from 147 companies now to perhaps as few as as 90 after 2017.

As I wrote this article, I started receiving texts and phone calls from industry sources about job losses in the Australia Council. Although the agency wouldn’t confirm it to me, several high-profile artform directors have been laid off, as well as tens, perhaps scores, of more junior staffers.

The turmoil comes as organisations across the country prepare their four-year funding applications. It’s hardly the best preparation for one of the most important funding decisions in a decade.

Not everyone is facing such uncertainty, however. Last week we learned that one of George Brandis’ favourite arts organisations, the Australian World Orchestra, was given $2.42 million in direct funding in September this year. The decision was not peer-reviewed and was made directly by Brandis himself. It came just days before Brandis was replaced as Arts Minister.

As prominent cross-media artist and director David Pledger wrote on Thursday, ‘the irony is exponential’. But that’s cultural policy under the Coalition, where the well-connected can secure patronage, while the majority of artists and organisations struggle.

Image by Sam Wallman.